Nam Kyu-hong, known for producing dating reality shows, focused on capturing the first moment a man and woman fall in love

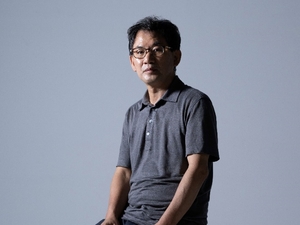

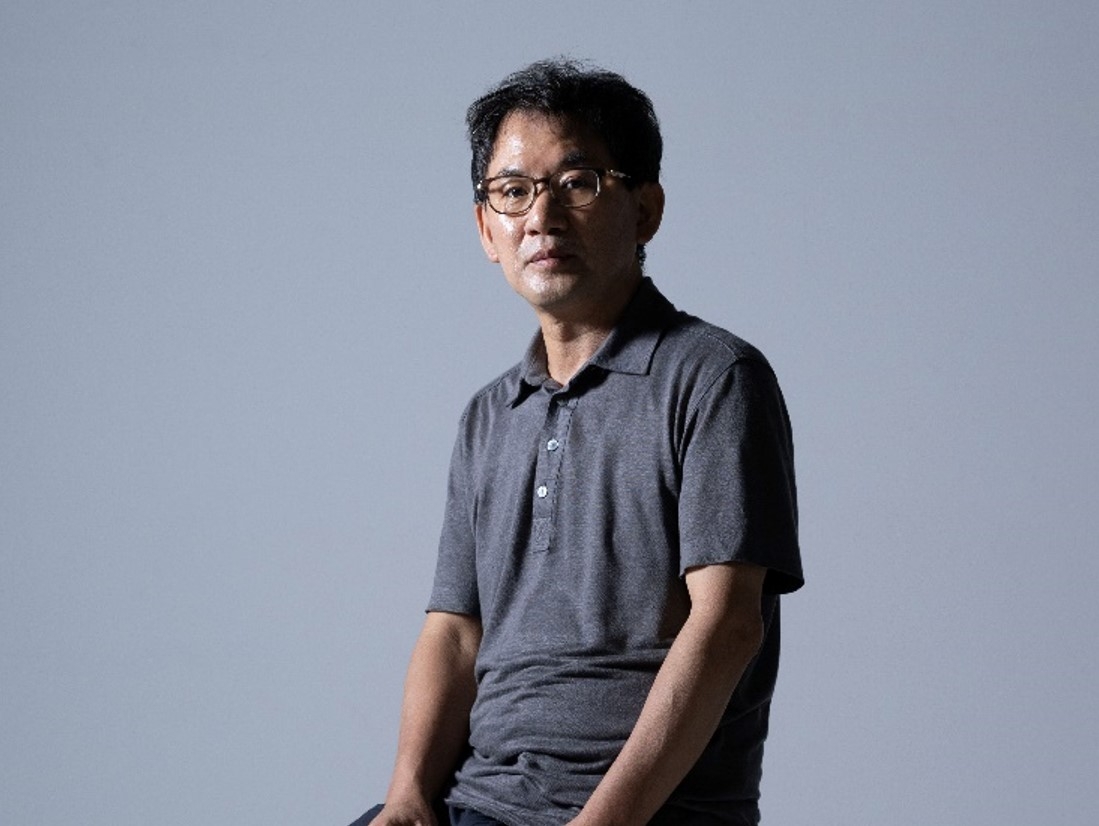

Nam Kyu-hong, a lead producer of SBS reality dating program “I’m Solo” (Im Se-jun/ The Korea Herald)

Nam Kyu-hong, a lead producer of SBS reality dating program “I’m Solo” (Im Se-jun/ The Korea Herald)

South Korea is awash with reality dating shows. But one program stands out above the rest: “I’m Solo.”

Unlike most dating shows, SBS’s “I’m Solo” does not feature glamorous casts. Instead, its contestants resemble the neighbor next door. They are office workers, small business owners or civil servants seeking actual partners. Through “I’m Solo,” a total of 12 couples have gone on to marry.

For viewers, the appeal lies not in romance itself but in the raw, sometimes awkward, ways contestants navigate relationships.

When episodes air, they spark a frenzy of online reactions. Comment sections fill up, YouTube channels dissect contestants’ behavior, and even Blind, a popular app for office workers, has a dedicated forum for “I’m Solo” viewers. For many fans, the program feels more like Producer Nam Kyu-hong’s social experiment than a dating show, exposing human nature in its unfiltered form.

“I’m Solo is closer to reality than most entertainment shows. It reflects our society, and that’s why people connect to it,” Nam said in an interview. “Some shows are just for laughs and then forgotten. This one feels like people’s own stories, like watching colleagues or friends try to find love. That makes it more than just television.”

A contestant on “I’m Solo” shows her name written on a scroll to the other person. (SBS)

A contestant on “I’m Solo” shows her name written on a scroll to the other person. (SBS)

To trace the roots of Korea’s reality dating genre, you have to go back to 2011, when SBS aired “Jjak” (which means “mate” in Korean). The show followed ordinary men and women living together for a week in a so-called “Love Village,” hoping to find a marriage partner.

Nam created the program with a simple question: How do men and women connect when they first meet?

“The most important things to humans are work and love. I wanted to capture the birth of love in reality,” he explained. “So the show does not use filters to make contestants appear more attractive, and the staff try not to interfere with the contestants’ actions.”

“We just provide the traffic signals, like a road system, so they can move on their own.”

When it comes to exploring love, the producer is confident that his work goes beyond what academic research can offer.

“Many psychologists and philosophers study love, but this program captures on camera what their research cannot: the raw, real process of men and women falling in love.’”

“Jjak” was canceled in 2014, and its spirit was revived in 2021 with the launch of “I’m Solo.”

In 2021, “I’m Solo” was launched. With the program’s rising popularity, applications have poured in. But Nam insists numbers mean little.

“Quality of participants matters more than quantity,” he said. “We look for diverse personalities without overlap, and usually people whose jobs or backgrounds are transparent. If you have nothing to lose, you can ruin a program. We prefer people with something at stake.”

The show often trends when conflicts flare or eccentric contestants appear, but Nam said sensationalism is not his goal.

“Controversy drives ratings, and that is what networks want. But I believe stability and longevity are more important. If the issues get too toxic, I hold back. Otherwise, the show won’t last,” he said.

The realism of the show does come with a cost. On “I’m Solo,” there were two instances where the show’s flow became awkward because contestants with criminal records were entirely edited out.

The realism sometimes fuels controversy. Loyal fans dissect cast members’ every move; critics accuse the show of manipulation or poor casting. Nam shrugs off the noise.

“In any society, opinions collide. If everyone liked the same thing, that would be fanaticism. I don’t read reviews or comments. I just focus on making the program well.”

SBS’s I’m Solo (ENA, SBS Plus)

SBS’s I’m Solo (ENA, SBS Plus)

How Korea’s dating culture has changed

Nearly 15 years have passed since he first began producing dating reality shows, and Nam has watched Korea’s views on love and marriage evolve.

“Back in the 2010s, most contestants were under 30. Now almost none are. Today, the mid-30s is the real marriage age,” he observed.

“Women’s social positions have also changed. They’re much more independent and assertive than before.”

When asked about Korea’s marriage market, Nam was frank.

“Sometimes it’s love, sometimes it’s the background. In reality, background matters a lot. TV makes it seem like looks and romance dominate, but in real life, backgrounds are more decisive.”

Here, background refers to social and economic factors such as education, occupation, housing and financial stability.

That philosophy extends to casting. Contestants with vague careers or unstable circumstances are avoided.

“We’re essentially introducing potential marriage partners. Why bring in someone whose life isn’t clear?”

A soon-to-be mom and dad have emerged among the 28th cast of I’m Solo. (Screenshots from SBS Plus·ENA’s I’m Solo)

A soon-to-be mom and dad have emerged among the 28th cast of I’m Solo. (Screenshots from SBS Plus·ENA’s I’m Solo)

Nam offered advice for Korean men and women of marriageable age.

He said it is important to look at how a person has lived, rather than just what they say. “Take a close look at the past 30 years of their life. You can tell whether it is a life that has been shrinking or one that has been growing. It’s like investing in a blue-chip stock. You want to make the right choice,” he said.

“It’s not just about someone’s job. Choosing a spouse is one of the most important decisions in life, and if you misjudge, the consequences are plain to see.”

Because Nam occasionally appears onscreen, viewers are curious about him, and many speculate about his worldview: Some call “I’m Solo” the producer’s own social experiment, some see him as a cynic, while others view him as deeply humanistic.

“If I were cynical about people, I couldn’t make this kind of show. The whole premise is about what it means to be human. You need affection for people to create this.”

His one strict rule when hiring staff or casting contestants: No graduates from elite school districts. “If producers lack basic compassion, the program could become dangerous.”

He gave the example of one contestant who was born and raised in Seoul’s Huam-dong. Nam said he chose her precisely because of that background.

“Huam-dong is a neighborhood of single-family homes where stepping outside means greeting grandmothers and grandfathers sweeping their yards.”

Growing up in such an environment, he said, can foster tolerance and understanding toward people from diverse walks of life.

While much Korean content is loved by global audiences, “I’m Solo” has not received as much attention abroad as it has at home.

“There’s no overseas version yet. That’s the difference from other shows,” Nam said. “I can’t do it alone — it requires broadcasters and markets. But if Netflix produced (an overseas) version, it would succeed without question.”

Indeed, “I’m Solo” has remained in Netflix Korea’s Top 10 for five straight years, outlasting even blockbuster dramas.

Asked to describe his show in one sentence, he said, “It’s about seeing humanity through the lens of love.”

shinjh@heraldcorp.com