In this report, we present a rare occurrence of bilateral primary nonrefluxing unobstructed megaureter in an adult, a condition typically identified in pediatric populations and infrequently reported in adults. The uniqueness of this case lies in its presentation with vague loin pain and the absence of significant complications, such as obstruction, infection, or impaired renal function, which are commonly associated with megaureters.

This case is particularly valuable for its rarity and for demonstrating the use of noninvasive imaging modalities in reaching a diagnosis. The combination of ultrasonography, CT urogram, and MAG-3 renal scintigraphy provided comprehensive anatomical and functional evaluation, allowing for accurate diagnosis without invasive testing such as VCUG or cystoscopy. In the absence of infection, obstructive patterns, or compromised renal function, the decision to manage the patient conservatively aligns with current best practices. Highlighting this approach is educational, especially for clinicians unfamiliar with the natural history of PMU in adults. While pediatric PMU is frequently encountered and well-documented, adult presentations remain under-reported, and our case underscores the utility of structured outpatient evaluation and follow-up to avoid unnecessary interventions [6,7,8].

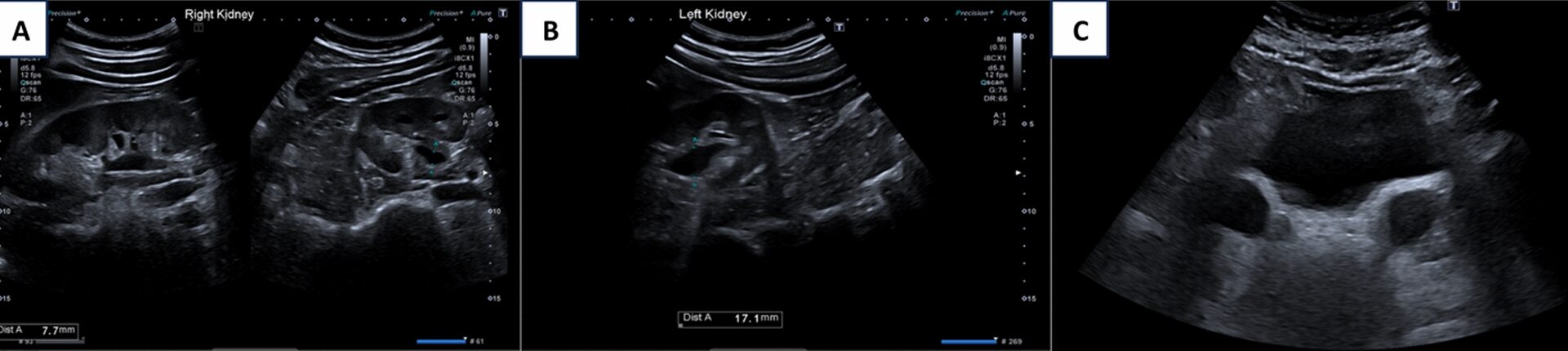

When the dilatation is not attributed to secondary causes, it is classified as primary nonrefluxing megaureter (PMU). PMU is often detected during routine antenatal ultrasounds and represents 5–10% of all cases of prenatal hydronephrosis (HN) [6, 8]. However, the incidence of prenatally diagnosed megaureter remains largely unknown, primarily owing to the challenges associated with accurate measurements using prenatal ultrasound. [4]. The classification of PMU grades is not formally standardized; however, a practical distinction can be made on the basis of the degree of dilatation: mild (7–10 mm), moderate (10–15 mm), and severe (> 15 mm). PMU is more frequently observed in males and predominantly affects the left ureter, though 25% of cases are bilateral. In unilateral cases, 10–15% are associated with an absent or dysplastic contralateral kidney [9].

The precise cause of megaureter remains unclear, although several hypotheses suggest potential abnormalities in the ureteral wall muscle fibers and irregularities in collagen composition or deposition during embryonic or fetal stages [10, 11]. In cases of nonobstructive, nonrefluxing primary megaureter, the condition may arise spontaneously or from unknown origins [12] .While there is not a definitive genetic inheritance pattern for the disease, some cases do seem to occur within families [13].

Ultrasound (US) is the primary imaging modality in the diagnostic evaluation of PMU and plays a crucial role in monitoring ureteral and renal dilation over time [6]. In addition to assessing ureteral diameter, ultrasound (US) provides valuable information about potential abnormalities in the kidney parenchyma, such as echogenicity, cystic changes, and parenchymal thickness. It also evaluates the anterior–posterior diameter of the renal pelvis, peripheral calyceal dilation, and bladder abnormalities [14].

Radiologically, hydronephrosis is either absent or present to a minimal extent in nonrefluxing, unobstructed primary megaureter [15]. While uncommon, a congenital megaureter can occur alongside congenital megacalyces, complicating the evaluation of hydronephrosis [16].

When evaluating bilateral ureteral dilatation in adults, it is crucial to consider a range of differential diagnoses beyond primary nonrefluxing unobstructed megaureter. Secondary causes must be ruled out systematically. Conditions such as neurogenic bladder, which can lead to functional urinary retention and bilateral hydronephrosis, should be considered, especially in patients with neurological symptoms or a history of spinal pathology. Obstructive causes including ureteral strictures, stones, or malignancy should also be excluded through imaging [17]. Inflammatory or infectious causes such as tuberculosis or schistosomiasis may mimic the radiographic appearance of a megaureter. In addition, acquired conditions including posterior urethral valves (rare but possible in adults), detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, or a poorly compliant bladder due to diabetes mellitus or chronic obstruction can lead to upper tract dilation. In our patient, the absence of lower urinary tract symptoms, normal renal function, and unremarkable findings on both ultrasound and CT urogram argue against these secondary etiologies. The use of MAG-3 renography provided additional reassurance by confirming nonobstructive drainage and preserved renal function, further supporting the diagnosis of primary nonrefluxing megaureter [6, 12,13,14].

PMU resolution is defined as achieving a stable anteroposterior diameter of the renal pelvis measuring 10-mm or less, and/or an SFU hydronephrosis grade of 2 or less, along with ureteral dilation of less than 8 mm [18]. Although PMU often resolves spontaneously [18], it is essential to accurately establish the diagnosis by ruling out other conditions associated with megaureter, such as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or posterior urethral valves. Differentiating these conditions informs the clinical approach, as a wait-and-see strategy may be appropriate for VUR [19], whereas cystourethroscopy should be considered if posterior urethral valves are suspected on the basis of voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) findings [20]. Accurate interpretation of urethral cystography is crucial, as assessing even indirect signs significantly improves the diagnostic accuracy of cystography for detecting posterior urethral valves [21].

The widespread adoption of prenatal ultrasound (US) has facilitated the early identification of PMU. Many of these cases remain asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously, enabling a nonoperative management approach [4, 18, 22,23,24,25]. Resolution of PMU typically occurs early, within the first 2 years of life [1, 18], though cases have been reported resolving as late as 5 years of age and occasionally into young adulthood [26]. However, ultrasound (US) is inherently variable, with results influenced by operator interpretation and the patient’s fluid intake. Therefore, it is advisable to assess ureter diameter during physiological bladder filling, with the expected bladder capacity for age calculated using the formula: [age (years) + 1] × 30 mL [26]. In the current literature, the rate of spontaneous resolution for PMU is reported to range between 34% and 88% [27,28,29].

Approximately 24% of patients with PMU require surgical intervention, particularly those with a mean ureteral diameter of 17 mm or greater, while the remaining 76% experience spontaneous resolution, typically within a median timeframe of 19 months [30]. An important predictor of spontaneous resolution in PMU is baseline ureteral dilation < 11 mm, as these patients are more likely to resolve within 24 months of age. Conversely, patients with ureteral dilation > 14 mm are more likely to require surgical intervention [1]. In addition, a nonobstructive washout pattern and presentation during the prenatal or neonatal period are also significant predictors of spontaneous resolution [19]. Given the potential for long-term complications reported in the current literature [31], it is recommended to maintain long-term ultrasound follow-up, at least until puberty. The duration of follow-up should be guided by the postoperative ultrasound findings, as symptoms can emerge even after years of observation [32].

The purpose of follow-up is threefold: (i) to confirm the resolution of PMU; (ii) to detect complications or worsening conditions, thereby assessing the need for surgical intervention; and (iii) to minimize painful procedures, radiation exposure, and economic costs through accurate risk stratification [32].

This case report is limited by the absence of long-term follow-up data and the lack of a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) to definitively exclude vesicoureteral reflux, as the patient declined this invasive procedure. While the diagnosis of bilateral primary nonobstructing nonrefluxing megaureter was supported by imaging and renal scintigraphy, the conservative management approach also limits the ability to assess histopathological or surgical findings.