Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the School of Advanced Computing have built artificial neurons that physically replicate the electrochemical behavior of real brain cells.

The study marks a major step toward more efficient, brain-like hardware that could one day support artificial general intelligence.

Unlike existing neuromorphic chips that digitally simulate brain activity, USC’s new neurons use real chemical and electrical processes to compute.

In other words, instead of just mimicking how the brain works, they function more like actual brain cells.

The work was led by Joshua Yang, Professor of Computer and Electrical Engineering and Director of the Center of Excellence on Neuromorphic Computing at USC.

Yang and his team have developed a new kind of artificial neuron based on what they call a “diffusive memristor.” Instead of using the movement of electrons like traditional silicon chips, these neurons rely on the movement of atoms to process information.

In the human brain, neurons use both electrical and chemical signals to communicate. When an electrical signal reaches the end of a neuron at the synapse, it turns into a chemical signal to transmit information to the next neuron. Once the signal crosses, it becomes electrical again.

Yang’s team has now recreated this same process using silver ions in oxide.

“Even though it’s not exactly the same ions in our artificial synapses and neurons, the physics governing the ion motion and the dynamics are very similar,” says Yang.

He adds, “Silver is easy to diffuse and gives us the dynamics we need to emulate the biosystem so that we can achieve the function of the neurons, with a very simple structure.”

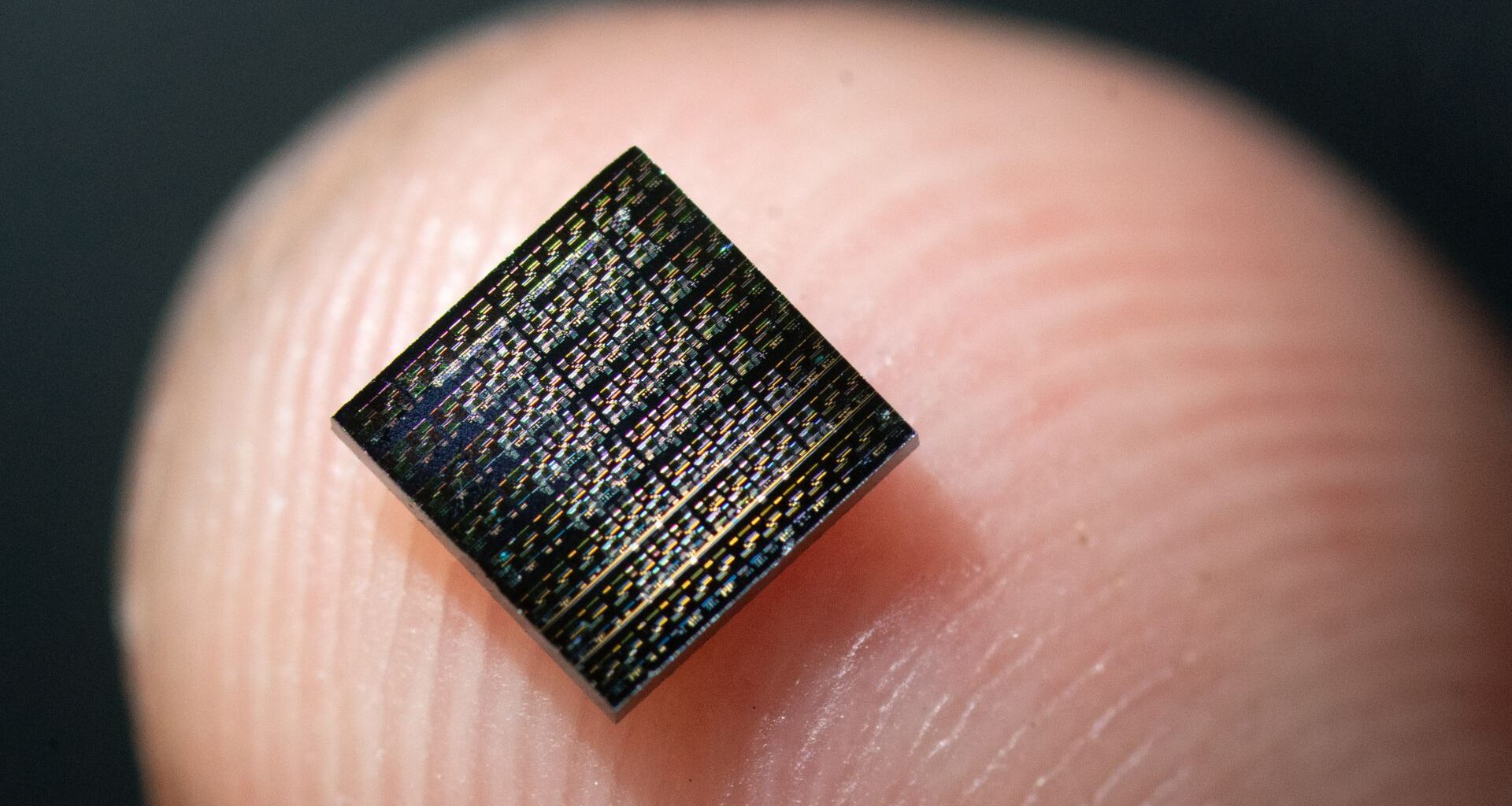

This design, called a “diffusive memristor,” lets each artificial neuron occupy the space of just one transistor, instead of the dozens or hundreds used in conventional designs.

Yang says the team chose to use ion dynamics “because that is what happens in the human brain, for a good reason and since the human brain is the winner in evolution, the most efficient intelligent engine.”

Energy efficiency at the core

Yang says the main issue with current computing systems is not power, but efficiency.

“It’s not that our chips or computers are not powerful enough for whatever they are doing. It’s that they aren’t efficient enough. They use too much energy,” he explains.

Modern computers are designed for processing massive amounts of data, not for learning from small examples the way humans do.

“One way to boost both energy and learning efficiency is to build artificial systems that operate according to principles observed in the brain,” says Yang.

He believes ions could be the key to that. “Ions are a better medium than electrons for embodying principles of the brain,” he says. “Because electrons are lightweight and volatile, computing with them enables software-based learning rather than hardware-based learning.”

Building toward artificial general intelligence

The human brain can learn to recognize something after seeing it only a few times and uses just about 20 watts of power to do so.

By contrast, today’s AI systems and supercomputers require massive amounts of energy for similar tasks.

Yang’s team hopes their atom-driven neurons can close that gap. “Instead [with this innovation], we just use a footprint of one transistor for each neuron,” he says.

The current devices use silver, which Yang notes is not compatible with standard semiconductor manufacturing. His team plans to explore other ionic materials that can offer similar performance.

Now that USC researchers have developed compact and capable artificial neurons, their next step is to integrate large networks of them and test how closely they can match the brain’s learning ability.

Yang says that in the process, such systems could also help scientists better understand how the brain itself works.

The study is published in the journal Nature Electronics.