We present a clinical case involving a 3-month-old female infant of Tanzanian origin who was admitted to our hospital owing to recurrent high-grade fevers that began during her first week of life. Each episode of fever lasted at least 1 week. Importantly, these febrile episodes were not associated with any vaccinations, and the patient did not experience any seizures during the fevers.

She had a history of multiple hospital admissions for severe sepsis and recurrent anemia, which required blood transfusions. Sepsis was documented to have been high-grade fevers, tachycardias, lethargy, and gastrointestinal symptoms, where she was treated with antibiotics. There was no history of jaundice or bleeding disorders. Upon admission to our facility, she was continuing a 6-week course of clindamycin treatment for osteomyelitis in her left elbow and thigh, initially prescribed by another health center. She was born at term via cesarean section, with a birth weight of 3.2 kg, and no significant perinatal events were reported. She had received appropriate immunizations according to Tanzania’s National Immunization Schedule. She was breastfed and supplemented with formula milk. At her first presentation, her developmental milestones were delayed for her age, as she was unable to control her neck at 3 months. She is the youngest in a family of 3 children, born to nonconsanguineous parents, and the two older siblings are well with no history of similar illness.

Upon admission, she appeared pale and febrile, with an axillary temperature of 39 °C. There were multiple mobile, nontender lymph nodes in both the cervical and inguinal regions, the largest measuring approximately 3 cm in diameter upon palpation. She had a warm, swollen left elbow joint and tenderness on her left mid-thigh. There were no dysmorphic features, frontal bossing, or hypertelorism. She weighed 4.5 kg and had a body length of 60 cm, which is below the third percentile for her age. Her occipital–frontal circumference measured 40 cm, placing her in the 25th percentile for age. In addition, she presented with an erythematous macular rash that was distributed across her trunk and extremities, as shown in Fig. 1. Other systems were unremarkable.

Skin manifestations of the index patient. A Erythematous macular rash with irregular borders on the lateral aspect of right leg and instep of right foot. B Erythematous macular rash on the anterior aspect of right leg and bridge of right foot (images for trunk lesions not available).

Initial investigations revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 20 × 109/L (5–15 × 109/L), absolute neutrophil count of 9.79 × 109/L (1.5–6.3 × 109/L), with moderate microcytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin count of 7.3 g/dL: [> 11.5 g/dL], mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 72 fL [74–102 fL], and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) of 23.5 pg: [23–31 pg]), thrombocytosis (platelet count 567 × 109/L [150–450 × 109/L]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 110 mm in the first hour (< 10 mm/hour), a C-reactive protein concentration of 167 mg/dL (< 5 mg/dL), and a serum lactate dehydrogenase of 547 U/L (120–300 U/L). A peripheral blood smear showed toxic granulations and microcytic hypochromic anemia without blasts. Urine culture grew Gram-negative rods sensitive to amikacin and ciprofloxacin but resistant to ceftriaxone, nitrofurantoin, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. There was no growth detected in the blood culture. Hemoglobin electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography both revealed hemoglobin AS (HbAS) reflecting sickle cell carrier state. Her parents were tested and her father was also found to have HbAS, while her mother had HbAA.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Gene X-pert for tuberculosis DNA were negative. To investigate the possibility of primary immunodeficiencies, she underwent screening for serum immunoglobulins. The concentrations of IgA, IgM, and IgG were all within normal ranges. Serum IgE was 2300 (< 100 IU), and CD4 and CD8 count were also within normal ranges. Serum immunoglobulin D (IgD) testing was not performed because it is a very rare cause of primary immunodeficiency, and our suspicion at the time was quite low. While genetic studies were recommended, they were not conducted owing to the unavailability of testing in the country and the high costs associated with international processing.

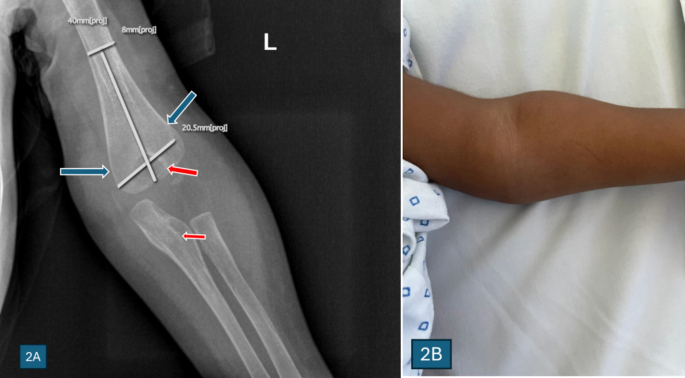

X-ray of the elbow and bone scan showed features of osteomyelitis and osteopetrosis of the distal humerus, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

A An X-ray of the left elbow joint of the index patient showed features suggestive of Erlenmeyer flask bone deformity (blue arrows) of the left distal humerus with a bone-in-bone appearance of the distal humerus and proximal ulna (red arrows), which are features suggestive of autosomal dominant osteopetrosis. B Swelling of the elbow

X-ray of the left leg, taken in the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral view. There is a periosteal reaction along the medial mid-shaft of the tibia with some ill-defined sclerotic changes in the adjacent bone, which is suggestive of osteomyelitis

She was successfully treated for osteomyelitis, initially as an inpatient, and then discharged to complete the dose.

In the following months, she was admitted several times and treated with various intravenous antibiotics, including amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, clindamycin, and fluconazole. Despite several weeks of treatment, there was little improvement, and the child continued to experience recurrent fevers and skin infections, eczema, persistent diarrhea, vomiting, and poor weight gain leading to failure to thrive, with a weight of 5.4 kg and length of 43 cm by 10 months of age, which were below the 3rd percentile for her age, and she could not sit without support.

At 18 months of age, her parents agreed to do the genetic studies. A CentoImmuno panel (sequencing and next-generation sequencing [NGS]-based copy number variation [CNV] analysis) was performed by Lancet Laboratories, Johannesburg, South Africa, in collaboration with Centogene Company of Germany. The genetic panel test revealed two heterozygous-like pathogenic variants in the MVK gene, the MVK variant c.346 T > C p. (Tyr116His) and the MVK variant c.829C > T p. (Arg277Cys), as presented in Table 1. These findings are consistent with those of mevalonate kinase deficiency (MKD) and hyper-IgD syndrome. These results, together with the constellation of clinical symptoms, confirmed the diagnosis of MKD in our patient.

Table 1 Main findings of the genetic studies for the patient in discussion

The child is currently 2 years old and is under regular follow-up, during which her symptoms have shown improvement. She weighs 10.5 kg, which falls between the 10th and 25th percentiles for her age. She is able to speak in two-word phrases, walk independently, and understand two-step commands. She is prescribed dexamethasone at a dosage of 0.5 mg once a day, given three times a week. This dosage has been tapered down from an initial daily dose of 0.5 mg. In addition, she is taking vitamin D, calcium, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (ibuprofen) as needed for fever. She has not started the recommended medication for MKD, such as canakinumab, owing to limited availability and high costs associated with purchasing these therapies in our setting.