London’s National Gallery is to build a major new extension, featuring nearly as much space as the present Sainsbury Wing. The project will cost around £400m, of which £375m has already been quietly raised behind the scenes—an astonishing achievement.

The pledges revealed today include two donations of £150m each. Gabriele Finaldi, the gallery director, told The Art Newspaper that these both represent “the largest-ever known cash donations to any cultural institution, not just in Britain, but globally”.

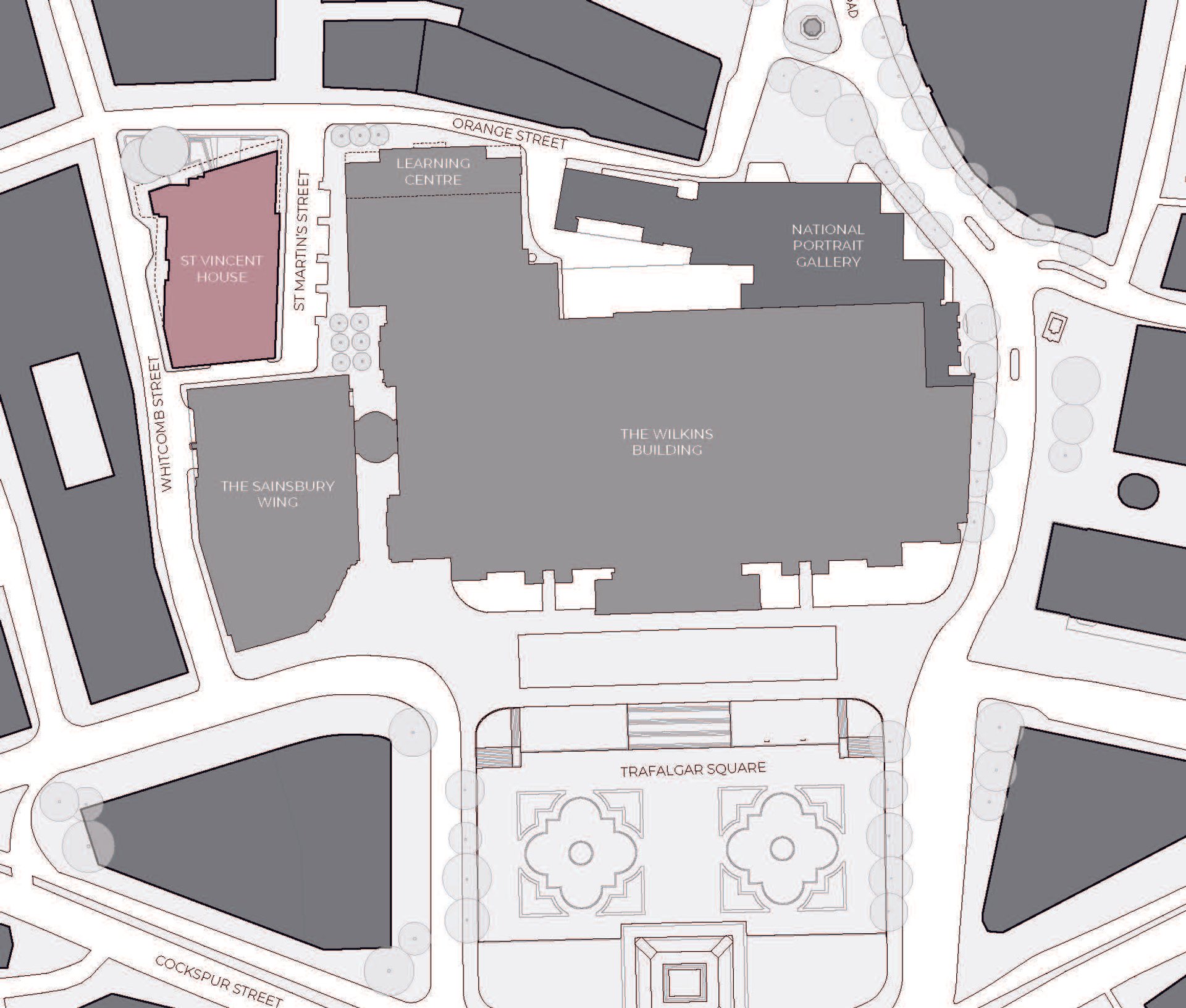

An international architectural competition for the extension will be launched on 12 September. The new wing, which is expected to open in the early 2030s, will be on the site of St Vincent House, an undistinguished 1960s building just to the north of the Sainsbury Wing. St Vincent House, now set for demolition, was bought for the gallery in 1998 to provide future land and much of it has been leased out (it currently houses a Thistle Hotel).

A view down St Martin’s Street, with St Vincent House on the right. In the distance is the back of the Sainsbury Wing

Photo: The Art Newspaper

Today’s other key announcement, which will have a revolutionary long-term impact, is that the gallery will start to collect paintings from across the entire 20th century. Until now its cut-off date has been around 1900, although since the 1990s it has occasionally acquired early 20th-century works. Finaldi says that the new acquisition strategy will be enacted in “collaboration” with Tate, which has long collected international art from around 1900.

Who are the record-breaking donors?

The two leading donors for the new wing are Michael Moritz’s Crankstart foundation and the Hans and Julia Rausing Trust. Cardiff-born Moritz, who lives in San Francisco, began his career as a journalist with Time magazine and went on to make his fortune as a venture capitalist with the firm Sequoia Capital, investing in Google, YouTube and LinkedIn.

Moritz’s funds for the gallery are channelled through Crankstart, a foundation he set up with his wife Harriet Heyman. He is committed to giving away half his wealth to charitable causes. In 2012 Moritz donated £75m to Oxford University, where he studied. He has also been one of the major funders of the Washington, DC-based Lincoln Project, which campaigns, according to its website, “to Stop Trump, Break MAGA, and Save America”. Moritz is an art collector, and owns several important paintings by Lucian Freud.

Hans Kristian Rausing inherited wealth from his family’s stake in the Swedish-based Tetra Pak food-packaging company. He and his second wife Julia Broughton, whom he met when she was a senior director at Christie’s, set up what is now called the Julia Rausing Trust. Julia died of cancer in April 2024. Rausing said in a statement published today: “This gift is given in her memory, so that others may discover the same beauty and inspiration in art that meant so much to her.”

Before this latest donation, the Rausing trust had already given more than £10m to the gallery for building projects, including the refurbishment of its largest room.

The trust has also supported numerous other art institutions, including donations of £1.5m each to the Museums Association and the Art Fund. On 19 August it contributed £100,000 to help buy a Barbara Hepworth sculpture for The Hepworth Wakefield. Three weeks earlier it had pledged £2.5m to save Acme Studios, which provides affordable space to artists in Deptford, south London. The trust gave £2m towards the 2023 refurbishment of the National Portrait Gallery and £950,000 towards the acquisition of Joshua Reynolds’ Portrait of Mai (around 1776).

Both donors have been honoured with knighthoods for their philanthropy. Moritz received his in 2013 and Rausing last June.

In addition to the £300m raised from the two lead donors, the gallery has raised a further £75m for the new extension. These include contributions from the National Gallery Trust and the chairman of the gallery’s trustees, the entrepreneur John Booth, who is personally contributing £10m.

What are the gallery’s hopes for the new wing?

The extension on the site of St Vincent House will be the UK’s largest museum building project since the £134m opening of Tate Modern in 2000 and its 2016 £260m extension. Finaldi has named it Project Domani (Italian for “tomorrow”), and it has been framed a successor to the NG200 celebrations, which looked back and commemorated the gallery’s establishment in 1824.

The estimated cost of the gallery’s wing will only be known after architectural plans are finalised, but it is likely to be around £400m.

The new building will be linked with the 1991 Sainsbury Wing, which since its refurbishment in May has become the main entrance. There is currently a lane separating the Sainsbury Wing and St Vincent House, known as St Martin’s Street, but it is hoped that this little-used road can be shortened, allowing the extension to “plug into” the earlier wing. It is also expected that a bridge would be built above a different section of St Martin’s Street to link an upper floor of the new wing to the gallery’s main building.

An aerial view of the National Gallery with St Vincent House marked in red

© The National Gallery, London

The plan is to use the two upper floors of the extension for part of the permanent collection. This would provide the equivalent of one and a half times the space currently occupied by the early Renaissance paintings in the Sainsbury Wing. The new wing would have space for hanging up to 250 pictures.

A temporary exhibition gallery would be housed on another floor of the extension; it would be around twice as large as the existing, equivalent space in the lower basement of the Sainsbury Wing. Plans for the old exhibition space, which suffers from a lack of natural light, are now being discussed, but it could be used to display the “reserve” collection—paintings of secondary importance currently housed in storage.

The new wing’s ground floor and basement will house public facilities. There will also be an energy centre, designed to provide more efficient power for the entire gallery.

Finaldi says that the gallery hopes to appoint an architectural firm next March. Ideally he would like a building that is “distinctive, of high quality and representing a significant architectural contribution to London, but that is also part of an architectural estate with the Sainsbury Wing and original Wilkins Building”. The scheme would also provide a more attractive walkway between the cultural hubs of Trafalgar Square and Leicester Square.

It might take the appointed architect a year to develop designs and another year to get the appropriate planning permissions. St Vincent House would then be demolished before construction begins, with the new wing expected to be completed in the very early 2030s.

Venturing into the 20th century

As part of the Domani Project the National Gallery is now taking the bold decision to expand the scope of its collection to include the full 20th century. At present its collection begins, chronologically, with Italian art of the 13th century and extends to works dating to roughly 1900, although in recent decades it has occasionally moved into the early 1900s.

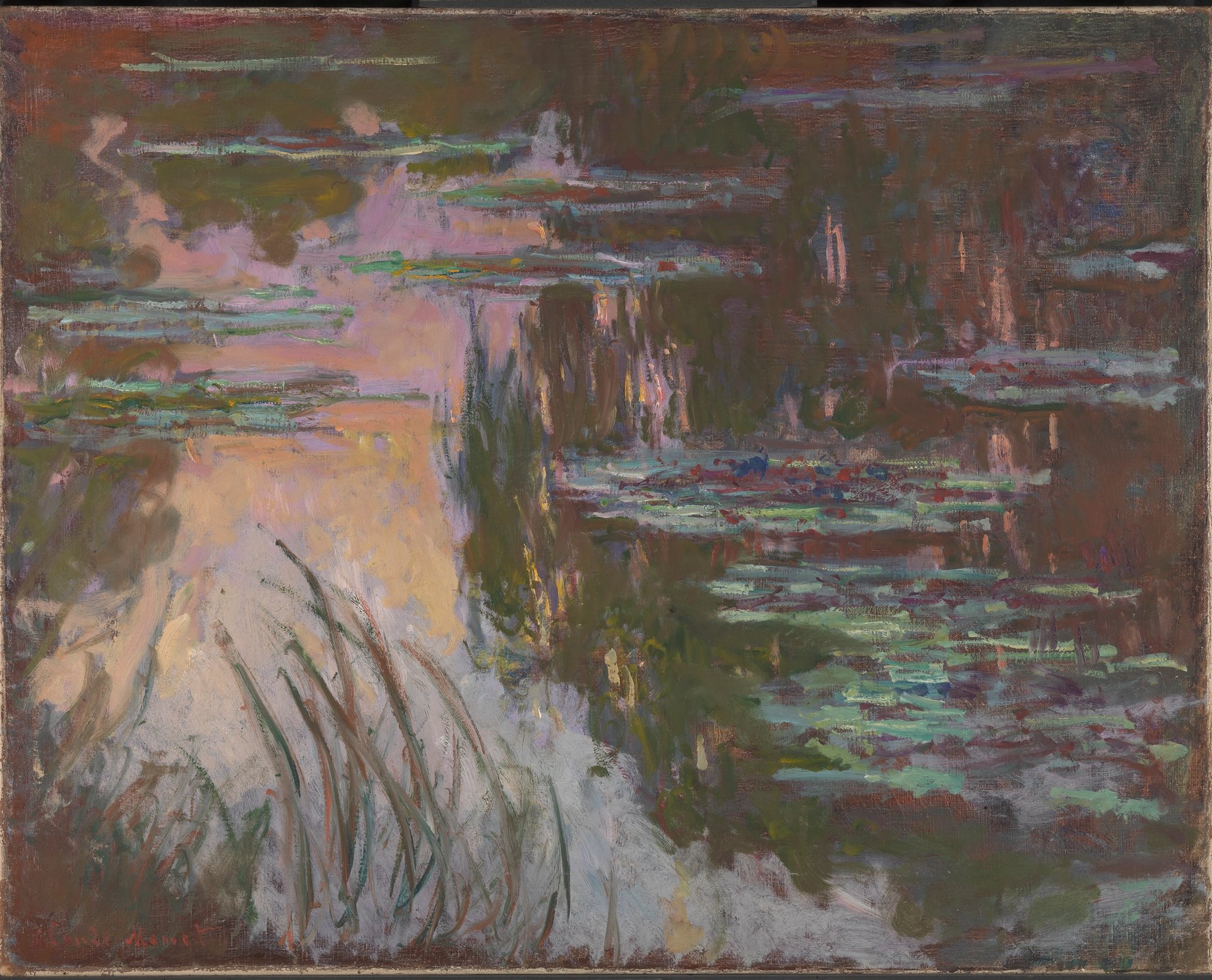

Finaldi envisages the 20th-century collection as starting with the later French Impressionists, then the arrival of Picasso and Matisse, the Italian Futurists, German Expressionists, Surrealists, American Abstract Expressionists, and up to the near the present, with a good chronological and geographical spread. No longer will the gallery’s collection be almost entirely European.

The 20th-century collection will be built up with both acquisitions and loans. Acquisitions will be dependent on raising yet more funding. To assist with loans, Finaldi intends to approach the estates of leading artists. With Tate, there would hopefully be an even greater exchange of loans between the two galleries.

Claude Monet’s Water-Lilies, Setting Sun (around 1907) is one of the relatively few 20th-century works currently in the gallery’s collection

© The National Gallery, London

The present approximate cut-off date of 1900 will need to be negotiated with Tate, which collects art from that year onwards. Finaldi has been in discussions with Tate director Maria Balshaw and the National Gallery hopes to reach a collaboration agreement by the end of this year.

Balshaw said yesterday: “Tate looks forward to working closely with colleagues at the National Gallery on loans, curatorial and conservational expertise to support the development of their new displays.” Both sets of trustees recently held a joint meeting and established a working group to collaborate and “further the national collection as a whole”.

According to Finaldi, the 1900 boundary “looks more and more artificial as time passes”. He points out that “painting becomes very exciting in the course of the 20th century”—and he wants the National Gallery to tell that story.

How will a visitor in the early 2030s encounter the new wing? Finaldi envisages that people will continue to enter the gallery by the Sainsbury Wing and proceed to the upper floor, where they would start their visit viewing early Renaissance works from around 1250 onwards. They would then enter the original galleries in the Wilkins Building, where the chronological sequence would take them to the far end, reaching the 18th century. There they would turn back in what would be a “horseshoe” configuration. This would eventually lead via a bridge into the new wing, where the late-19th and 20th century works would be displayed.

Finaldi stresses that the National Gallery is a “paintings gallery”, not an “art gallery” with sculpture and works on paper. By including the 20th century, he says that it will become the world’s most comprehensive paintings gallery, covering the story from its origins in the 1250s right up to now.