One day back in 2021, after about a month of weekly sessions, my therapist urged me to get assessed for ADHD. At the mention of ADHD, my mind went back to the ’90s classrooms I longed to escape from, full of tween boys hawking spitballs past motivational posters with kittens on them. Those kids definitely had “ADD.” I was just a daydreamer back then, a hair-twirler who frequently forgot her textbooks at home and doodled endlessly on notebooks and desks. Surely, I had nothing in common with the hyperactive boys of my youth who ate glue for fun.

ADHD’s a brain disorder, like OCD, that has become a part of our cultural lexicon, and one used as a personal punchline by many women trained to excuse themselves and apologize for living. When I heard I might have it, my first response was in line with this conditioning: “Well, doesn’t everyone have a little ADHD?” No, it turns out. ADHD affects approximately 2 to 4 percent of adults worldwide (although if we account for the undiagnosed, that number is likely much higher).

Once I became aware of adult ADHD, it was everywhere. The online tracking gods had my number, and social media fed me an endless supply of on-theme memes and TikTok videos. I could relate to the feelings of confusion, overwhelm, and shame people were depicting, but I still wasn’t convinced I could have it. I viewed ADHD as an excuse for being scattered and disorganized, and I wasn’t ready to excuse myself. Not yet.

My assessment with a psychiatrist was long and taxing, detailing the inner workings of my mind and my experience of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The report came back a week later, and I was officially diagnosed with ADHD at 39 years old.

getty images

Learning I have a neurological disorder that emerges in childhood baffled me at first. I showed many of the symptoms, so how did no one notice it for over three decades? I started looking back with suspicion, then anger, at the many signs that my parents, teachers, doctors, and caretakers not only missed but also turned into personality flaws: “She’s lazy,” “She has her head in the clouds,” “She gives up too easily,” “She’s careless,” “She’s a klutz.”

I dug into the research conducted on girls and women with ADHD with a sinking feeling in my stomach. In 2022, while chatting with UC Berkeley distinguished professor of psychology Stephen Hinshaw, a leading expert on the subject and one of the first researchers to study girls, so much of what felt off about these massive holes in ADHD research was confirmed for me. I asked Hinshaw what the field was like when he first started studying the disorder, and he told me that in the 1980s and ’90s, most people assumed girls just didn’t get ADHD. “The beat went on with that stereotype, no one did any research and girls kept getting ignored,” Hinshaw said. “I’m an objective scientist, but I had a hunch the field was full of shit.” (He was right.)

In 2022, I put out a call on social media to survey women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood, and heard from 40 of them. Some filled out a Google form I made full of invasive personal questions, others exchanged emails or texts with me, and a few I chatted with (and we’re besties now, obviously). They ranged in age from their early twenties to their fifties, but most of them fell into the 34-to-50 age range. They were honest, vulnerable, and beautifully generous with their stories. They were also grappling with the pain that comes from learning something essential much later than you should have. Many of us were undiagnosed in childhood, only to see our issues compounded by the time we reached adulthood. We got used to being, and feeling, invisible.

“I always thought I was a uniquely fucked-up fraud. Discovering that I was actually part of a big, chaotic sisterhood felt like being ushered into a secret group that I’d been searching for my entire life.”

Since an immense loneliness, born of feeling like an outsider in most school, work, and social situations, had defined so much of my life, it was baffling to consider myself one of many. The imposter syndrome that has followed me since childhood had another reason to torture me. I always thought I was a uniquely fucked-up fraud. Discovering that I was actually part of a big, chaotic sisterhood felt like being ushered into a secret group that I’d been searching for my entire life. It was cathartic, hearing from other people whose life experiences mirrored mine. I felt less alone in the world. I refer to us as ADHD’s lost generation because we were all overlooked and suffered for it in similar ways. This made me want to create some kind of Island of Misfit Toys for us to just talk, heal, and validate one another. I don’t have those kinds of resources, so I wrote a book instead.

getty images

I decided to call us “Nowhere Girls” because we’re a group of women who have felt like we were running, without a destination, from our emotional demons for most of our lives; because finding out, or even considering, that there was something larger at play than simply being fuckups who couldn’t get our shit together is a process that often plunges us into grief and anger at the way we’ve been treated. And at the way we treated ourselves.

Nowhere Girls are a cohort that science left out of studies and literature for decades, and the impact of this extends far beyond the pages of the papers we should’ve been included in. Too many women of this generation grew up missing a pretty essential piece of information about themselves, one that has likely touched every aspect of their lives.

What being undiagnosed, untreated, and ignored for most of our lives means for Nowhere Girls is incredibly complicated. A late diagnosis forces one to look back and filter the past through a different, hopefully kinder lens, but the process of reliving your entire life in order to change your mind about it is gnarly.

Many Nowhere Girls told me that they were branded as daydreamers or chatterboxes in school, but since we didn’t act out or fail our classes, teachers and doctors had no reason to suspect we had ADHD. When they did alert our parents that something was wrong, as my seventh-grade math teacher did, it was usually done in a way that placed blame on us instead of considering issues beyond our control, reinforcing the myth that we were simply slacking off or unmotivated.

getty images

The ways ADHD presents in women might seem complicated, but let’s not get it twisted—the biggest reason girls didn’t, and don’t, get diagnosed with ADHD as much as boys is because we were not considered in the research for many decades. You need only look at the rise in adult women being diagnosed with the disorder to see that there’s a major course correction currently under way, and it’s been a long time coming.

Becoming a part of this course correction and looking back at my own history has answered many questions I had about my brain and life experiences. But more important, it’s also quieted my most frequent question to myself, which for a long time was, What the hell is wrong with you?

The research is finally catching up for those of us left behind. Flawed as they might be, the studies from the past few decades prove that while a strong contingent of women with ADHD fall into the high-achieving, high-masking Type A category, a lot of us are also likely to have histories and lives that match our chaotic brains.

We are everywhere. In my regular little life, most of my friend group has been diagnosed, or has started to identify as neurodivergent, since my own diagnosis. I also run into, on average, one woman per week who has been recently diagnosed with ADHD.

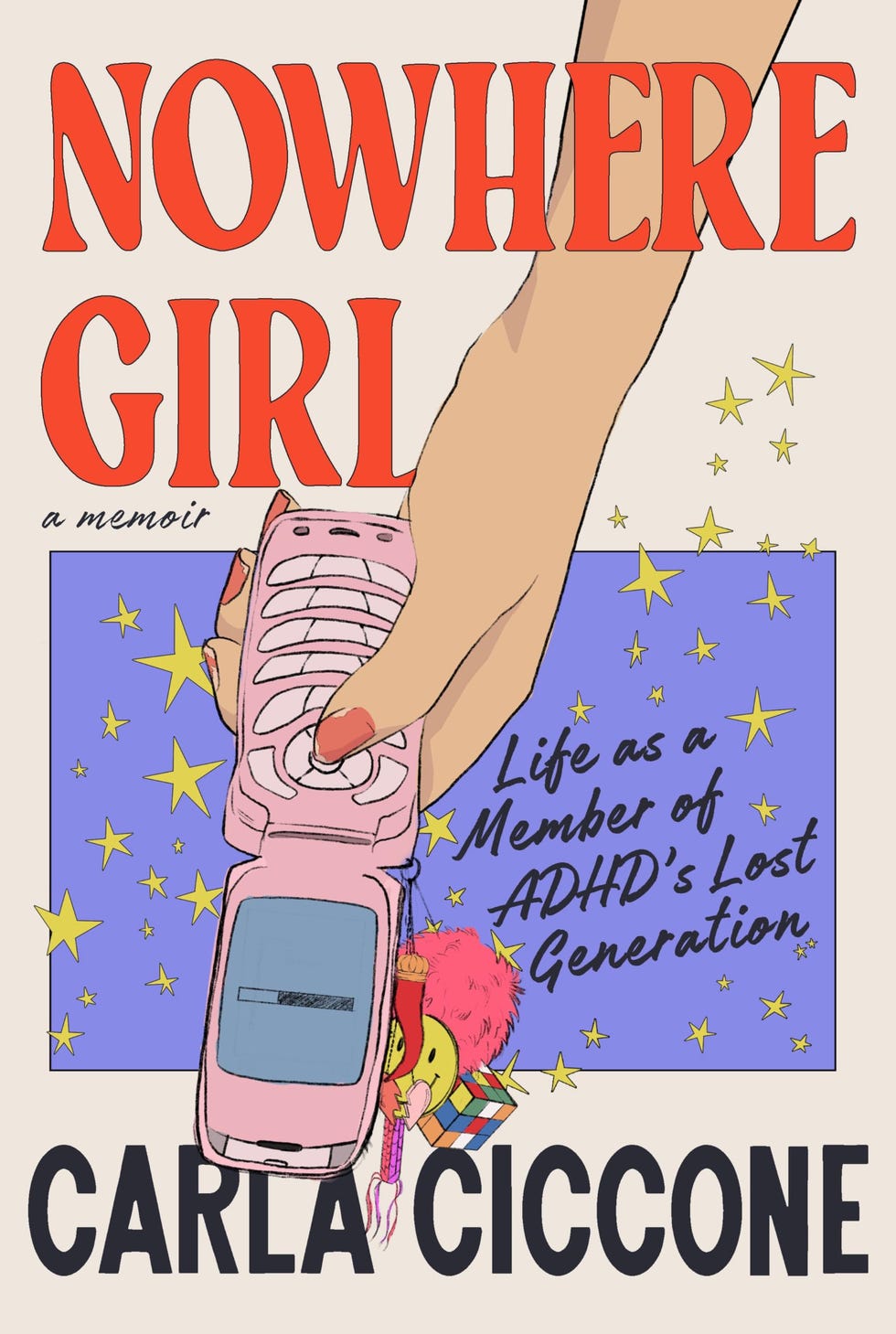

Nowhere Girl: Life as a Member of ADHD’s Lost Generation

Everyone invited late to the ADHD party has felt a sense of relief to have a diagnosis to point to, but our emotions are in conflict. We are sad and frustrated about the time we’ve wasted on doubting and blaming ourselves for being different. A lot of us are angry, and we have every right to be, especially since many of us grew up with our anger denied and rejected. Owning that anger and learning to live with it is just as critical as our need for gentleness and self-reconciliation to recover from the emotional ramifications of a lifetime of shame and self-blame.

There’s a generational reckoning under way, with girls who are now women finding out there’s nothing “wrong with” us, our brains just operate a little differently, and we have the scars to prove it. Nowhere Girls are not only the girls science forgot. We are the girls who’ve been bending ourselves into uncomfortable shapes for our entire lives, ashamed that we’re unable to perform life with the ease that other people seem to. We became great pretenders, or tried to. Many of us masked our discomfort and pain with alcohol, drugs, and by taking destructive risks. We deserve explanations, empathy, and second chances.

Even though the history of ADHD is fraught and the disorder itself complicated and sometimes controversial, we can choose differently for ourselves now that we know more. We deserve to experience the ease that has eluded us thus far. No one is going to give this gift to us. We have to take it.

Adapted excerpt from NOWHERE GIRL by Carla Ciccone. Copyright © 2025 by Carla Ciccone. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Related Stories