RALEIGH, N.C. — It was her second time trying to reverse what was supposed to be irreversible. The first time, Maranda Bordelon saved up for the $1,500 deposit, then booked a surgery date a few months out, so she’d have time to cobble together the remaining $4,500 she’d need to undo her sterilization. But just before her appointment, her parents’ house burned down, and she couldn’t stomach not being there to help. The deposit was non-refundable. That was in 2020. This time, instead of seeing that same surgeon, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from her home in Marksville, La., she’d picked a clinic six states and nearly a thousand miles away.

It was Dr. Charles Monteith’s website that convinced her: hundreds of pages of testimonials, newborn after newborn, fat-cheeked, wide-eyed, caught mid-giggle or mid-wail. Many of them wore T-shirts that said, “I’m a Monteith miracle.” The families had come to Raleigh from everywhere, it seemed. Arizona, Iowa, Utah, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Florida. When they’d arrived, the moms’ fallopian tubes had been closed: burned or clamped or cut or obstructed with metal coils. When they’d left, the tubes were reopened, ready for fertilization. It would cost $7,500, plus travel. Bordelon had started saving up again.

“We’re leaving here broke,” said her fiance, Kaleb Gentry, with a hint of pride, when they finally arrived in November 2024. “We’ve spent everything we had to do this.”

She was a nurse, he was a foundation driller, each one tattooed with the other’s name — and here was Monteith himself, familiar from YouTube, same black scrubs, same gap-toothed smile, giving them his pre-op spiel. “What makes you want a reversal?” he asked.

“We got together after I’d already had my children,” Bordelon said. She was 27. They were both from Marksville, a speck of a city where cotton had given way to corn and soy, the fields carved out of the bayou. They had mutual friends, and he’d slid into her Facebook messages. She’d joked she was nothing to be fixated on, she had bad credit and a bunch of kids. He’d replied he had good credit and no kids. He took her bowling with four of his cousins. He seemed like such a catch, she wondered if he was a serial killer or something, why he was single.

“Did you look into IVF at all?” Monteith asked.

“I did a little bit, but I’d kind of rather do it the full natural way.”

“I hear that a lot, ‘the natural way,’” Monteith said. “Having sex is more fun than getting stuck with needles.” Bordelon giggled. In some respects, theirs was a classic tubal ligation reversal story, the story Monteith heard most often: Tubes tied young, when she already had kids and thought she was done. Then she’d gotten divorced, met someone new who had no kids of his own, realized maybe she wasn’t as done as she thought.

How doctors are pressuring sickle cell patients into unwanted sterilizations

But there was another reason she wanted this surgery, another reason IVF wouldn’t do. Ever since she’d had a segment of each fallopian tube removed, she’d been living with terrible pain. It would start a week before her period and linger afterward, lasting the better part of a month. She thought it was appendicitis at first; it sent her to the emergency room. Then it just became her new, unlivable normal. She kept having to leave her nursing shifts at the psych hospital, curl into bed, and wait for pain meds to kick in.

Post-tubal ligation syndrome, as it’s known online, is a lesser-known instance of a now-familiar curse: a set of symptoms debilitating enough to unravel lives but inexplicable enough for many doctors to doubt it’s a syndrome at all. After all, tubal sterilization is among the most common forms of female contraception. Some 700,000 Americans get one every year. Per the medical literature, as surgeries go, this one is safe.

Those with PTLS beg to differ — at least for some uncounted subset — and they point to their 15,000-member Facebook support group as evidence. The mismatch sends women on maddening pilgrimages in search of recognition and relief. The best remedy, many with PTLS say, is reversal: Almost like turning back the clock, reverting to your pre-sterilization self. In fact, the first time Bordelon had put a deposit down to have this procedure in Louisiana, she was a single mom with three small kids at home, not looking to have another; she’d just wanted the symptoms to end.

That odyssey can lead not only into the operating room, but also into a tug-of-war with mainstream medicine, which recently has drawn some — be it avidly or uneasily — into the data-distrusting orbit of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Bordelon and her daughter make dinner and dessert together in their kitchen.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon and her daughter make dinner and dessert together in their kitchen.Emily Kask for STAT

Is there evidence for a post-tubal ligation syndrome?

A contested illness presents a catch-22. With data limited, definitions fuzzy, and causes uncertain, some doctors are unconvinced. But how to collect data when it’s hard to define exactly what you’re collecting data on? The strict stipulations and cutoffs that help make something studiable and diagnosable may well leave out some of the very patients who already feel brushed off. It’s true of long Covid, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia, too. Each one comes with this secondary affliction: not just the symptoms themselves, but the rift between official medical knowledge and people’s accounts of what’s unfolding within their own bodies and lives.

For Amy Barnett, it began right after her tubal ligation, during the birth of her second child, with an electricity-like pain crackling from her belly into her legs. When she asked whether her surgery might’ve sparked this, the nurse said no. Doctors told her everything looked normal. She wound up in a wheelchair, unable to walk even a few steps to the bathroom. Eventually, fed up with Barnett’s mysterious disability, her OB-GYN refused to see her. She was accused of drug-seeking when she went to the ER.

The only plausible explanation she could find came from Google. When she looked up her symptoms — she would count around 32 of them — she happened upon a blog about PTLS affiliated with a Dr. Vicki Hufnagel. This had to be what she had. Only later would Barnett learn that Hufnagel was an anti-hysterectomy crusader who had lost her medical license in the 1980s amid a storm of lawsuits, accused of comparing herself to Galileo, botching procedures she claimed to have invented, and submitting fraudulent bills.

Hufnagel had denied those claims and sought, unsuccessfully, to get back her revoked credentials — but even decades after the fact, Barnett saw that any semblance of an association between Hufnagel and her own attempts to get her PTLS recognized would hurt her cause. She wanted the condition studied, legitimized, not further discredited. When she began setting up online support groups in 2011, and became a PTLS social worker of sorts, she was careful never to steer fellow sufferers toward anything Hufnagel-tinged. She knew that the outside world was already primed against them.

“When you hear about it, you think, ‘OK, these are a bunch of kooky women, they’ve developed some sort of cult, and they’re just completely against tubal ligation.’ That’s not true,” Barnett said. “I’m all for being able to make an informed choice.”

What doctors should tell sterilization-seeking patients about PTLS, though, is itself contested. They had to discuss risks — but where did responsible disclosures end and fearmongering begin? As early as 1951, there were statistical blips suggesting that some version of PTLS might be measurable in studies — but they were often eclipsed by findings suggesting it wasn’t. A 1998 review titled “Is there any evidence for a post-tubal sterilization syndrome?” reported a possible yes for women in their 20s who’d previously had menstrual issues — but a no for women over 30. A big New England Journal of Medicine study from 2000 found that women who’d had tubal ligations described more menstrual irregularities than those whose partners had had vasectomies — but significantly fewer instances of pain and heavy bleeding. A few more papers, and some doctors considered the question settled: The data showed no consistent link between sterilization and these symptoms.

That depended on what sort of data, though. Sufferers couldn’t help but see patterns in their stories — affecting only a small minority of women, perhaps, and so diluted in the wash of studies, but worth addressing. Even when researchers explicitly set out to address patients’ concerns — to bridge the gap between doctors with expertise in study design and people with expertise in their own bodily experiences — the community still felt dismissed. Barnett served as an adviser on a 2021 study, but ended up alienated. “Unfortunately, the scientists did not include most of the symptoms that we wanted to look at,” she said. It was the same vicious cycle contested illnesses are often caught in, academic medicine reaching for stricter criteria than patient groups. When the study came out, Barnett distrusted the results.

There was already plenty of distrust to go around, with doctors repeatedly telling those with PTLS that their illness was all in their heads, that they were depressed or suffering from personality disorders or merely exhausted. It was hard not to see, in such dismissals, a generalized shrug about women’s pain, and with it, a kind of critique. Motherhood is a medical and moral battleground, its every detail attracting judgment with an almost magnetic pull, people judging you for having too many children or too few, for breastfeeding or for not breastfeeding, every parenting decision a referendum on your worthiness and character. When Stacey Underwood, a real estate agent in North Carolina, told her doctor about her symptoms, his diagnosis was a maladjustment to having five kids, his prescription for a babysitter. “It made me feel like my role as a mother was under attack, like I was not good enough,” she said.

Some found in Barnett’s Facebook group what mainstream medicine could not or would not provide. “Amy was amazing. She would message me. She would talk to me, answer my questions,” said Misty, who’d found herself using a walker at 38 and bleeding out clots the size of golf balls, and spoke on condition that her last name not be used. “I just felt like a vampire who finds other vampires at a convention.”

Tubal ligation reversal, a ‘dying art’

Tubal ligation reversal sits on the outskirts of American medicine, in a weedy gray zone, not quite shunned by the establishment, but not quite part of it, either. The guidelines are clear: Sterilization must be considered permanent. Undoing it is sometimes possible but never certain. Some 65% of reversals result in pregnancies, a 2023 analysis found, but the number can depend on age, health, and surgical methods used. For many, the success rates are moot. While ligation is typically covered by insurance, reversal almost never is, and thus is often unattainable. It suggests the judgy economics of just-desserts: You can change your mind, but you’ll have to pay for it yourself.

Hospitals offer the procedure, but the overhead expenses mean it can cost in the tens of thousands of dollars. It’s also become rarer since the advent of in vitro fertilization in the 1980s, which many doctors prefer. By siphoning out eggs with a needle through the vaginal wall, physicians can circumvent blocked tubes without surgery; by relocating reproduction to a lab dish, they gain more control over various sources of infertility, male or female. Some training programs no longer teach reversal at all. “It’s a dying art,” said Eliran Mor, a Los Angeles-area reproductive endocrinologist.

All this gives it a contrarian allure, creating a niche for businesses like Monteith’s. He relishes his outsider status. He’d spent his early career as a more traditional OB-GYN but eventually began to feel like a cog, and left to apprentice himself to an older reversal surgeon. When his mentor retired to open a medical spa, Monteith took over the practice.

To prevent ovarian cancers, fallopian tube removal is on the rise

That sense of being different from other doctors is an essential part of his spiel. The day before Bordelon’s surgery, he pulled up his website to show her how to send in a baby pic if the operation were successful. “You get pregnant, you let us know,” he said. “Under ‘testimonials,’ come down to ‘patient reporting.’” He scrolled and clicked. “The reason I put all this on here is that a lot of doctors don’t think this is possible, and they put the patients down.”

By his estimation, post-tubal sterilization symptoms are the reason for only about 5% of the 600 or so reversals he performs every year. Another 10% are motivated both by those issues and the desire for another child. The vast majority just wanted another child. But even that largest group has, in Monteith’s view, been alienated by mainstream doctors, who sometimes talk about medical decisions as if they took place in a sterile, mathematical realm, divorced from the tangled stories of people’s lives.

“Most infertility specialists just think of this as a way to get pregnant,” he said. “So when they talk about IVF versus tubal reversal, they just throw out statistics. But those statistics are meaningless to a person who wants to undo a prior mistake.” His work, he knew, was part physiology, part symbol.

Bordelon shows a tattoo memorializing her son.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon shows a tattoo memorializing her son.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon’s tattoo for Gentry.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon’s tattoo for Gentry.Emily Kask for STAT

‘I never got to plan to be pregnant’

Bordelon knew all about wanting a fresh start. She’d had her first child at 16, her second at 18. Soon, she was married, and her husband whisked her off to Mississippi to take an internship as a welder. She had two more kids, one at 19, another at 20. She’d tried all kinds of contraception — the pill, the patch, the shot, an IUD — but none had worked for her. Each time she’d found out she was pregnant, the news didn’t feel exciting. A tubal ligation seemed like the only option. She was far from home in a relationship that was foundering, her husband working nights. They hardly saw each other and had little to say when they did. “We were basically like roommates,” she said.

When it appeared, her pelvic pain was layered onto all this isolation and heartache. Then, in 2020, her youngest died at 18 months old, of sudden infant death syndrome. His name was Hudson. Their love for him was what had kept Bordelon and her husband together; now, he was gone. They got divorced. Within a year, she was a working single mom, seeing specialists for a mysterious chronic illness, bringing her older kids to decorate their younger brother’s headstone for Christmas and Valentine’s and Mardi Gras.

Though she didn’t know it at first, she represented a new life for Gentry, too. They’d been dating for a few months when she found out about his meth addiction. They were in the car, in search of corn-on-the-cob fabric for her daughter to wear in the “niblet pageant” at the Bunkie Corn Festival. They’d struck out at Hobby Lobby; she was using his phone to look up directions to Joann Fabric and Craft when she saw what looked like a message from a dealer.

What’s this, she demanded.

He’d been meaning to tell her. It had started when his first wife had gotten cancer. He’d be up all night, caring for her, then head to the construction site in the morning, exhausted. A buddy handed him some speed to help. He’d gotten hooked — and still was when he first started spending weekends at her house. He hid his meth pills in Tylenol bottles. But he swore he’d been sober for a month, that she was the best thing that ever happened to him. He begged her not to throw him out.

It felt like a betrayal. She couldn’t believe there had been drugs around her kids. Then again, her times with Gentry had been among her happiest. She loved watching him with her children, how he took them fishing and squirrel hunting on the bayou by their house, the pride he took in them. Plus, she had noticed a change in him recently, his disposition less irritable, his body filling out. Maybe he really had kicked his drug habit.

At first, she brought drug tests home from work and made him pee in a cup. He did it willingly, almost joyously, excited to prove he was sober still. Eventually she stopped. All around were stories of people who’d been lost or who’d pulled themselves back from the brink. The memory of one buddy inked on Gentry’s hand, a guy who’d been sleepless for days on speed and died in a car crash at 21. Their pastor, who’d managed to kick meth and find God.

Gentry was the one who first brought up the idea that they have another child, maybe two. Bordelon had already tried to get a reversal as PTLS treatment. A specialist she’d seen more recently had suggested it as a possibility — and she felt a yearning for a baby, too. She thought about how all four of her pregnancies had been surprises, her mind kicking into a clear-eyed anxiety. “I wanted the full experience,” she told Monteith. “I never got to plan to be pregnant. Getting excited to test positive is different than, like, ‘uh-oh.’”

The sheer amount of effort they had to put in was a testament to how committed they felt. This time, it would be the opposite of unplanned. “The route that me and Kaleb took to have a baby means a lot more to me than just finding out I was pregnant,” Bordelon said. “We’ve saved money, scheduled a surgery, traveled across the country to this random doctor’s office in this random place.”

The family prays before dinner together.Emily Kask for STAT

The family prays before dinner together.Emily Kask for STAT

How PTLS symptoms can remap someone’s world

There’s a Google doc that gets passed around the PTLS community to help people find these “random” doctors — a crowdsourced cheat sheet for a hard-to-navigate realm. Some surgeons won’t perform reversals unless the patient is planning to have a child. Some will remove clips from the fallopian tubes but won’t look for them if they’ve become dislodged and wound up somewhere else. One doctor in Tennessee will only do reversals for married women. It’s a kind of TripAdvisor for those in search of a very specific sort of trip.

“Believes in PTLS,” some entries say. Or: “does NOT believe in PTLS.”

“BELIEVES IN PTLS-per his website but denied it in the past-approach with caution.”

“Will accept patients with BMI over 40!”

“Noted to be caring and understanding of PTLS symptoms- DOES NOT PERFORM REVERSALS”

Illness can remap your world. What was once a daily activity now requires a calculus about conserving energy. The professionals who might’ve earned reflexive trust now seem hapless if not downright harmful. It can start with fallopian tubes and expand outward, to encompass everything.

For Barnett, what began with PTLS led to concerns about surgical clips, which case reports have found might spark an inflammatory response in a minority of people. She discovered her body contained them not only from her tubal ligation but also from previous gallbladder and thyroid surgeries. She flew to Raleigh for a reversal, to Austin for one clip removal operation, to Boston for another. She started another Facebook group and Google doc devoted to clip issues, advocating for surgeons to screen patients for metal sensitivities before any procedure. She wondered if PTLS might share some explanations with other contentious syndromes that seemed further afield but that were also hypothesized to stem from foreign substances in the body, such as breast implants, surgical meshes, or certain ingredients in vaccines.

Her illness influenced her thinking more generally, too. In the lack of discussion about PTLS before sterilization, she couldn’t help but see the same erosion of informed consent that she saw in vaccine mandates. She wouldn’t post about that in her Facebook group. There’s a rule against “political, vaccine, or religious debates.” Still, it shaped her personal politics.

In 2024, you might say she was a single-issue voter, her issue being bodily autonomy. To her, Kamala Harris represented vaccine mandates, President Trump represented the overturning of Roe v. Wade. She couldn’t stomach either one. She’s a registered Republican who often votes Democrat, a woman whose religious beliefs disallowed abortion for herself but who knows there are obstetric scenarios unimaginable until you’ve lived them. She cast her ballot for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for president, knowing he couldn’t win.

But once he became Trump’s health secretary, her hope was tinged with unease. She liked his stance against artificial food dyes, his scrutiny of rare vaccine adverse events, his vow to fund research into the causes of autism. Yet some of his claims struck her as crazy. The myth that poppers, rather than HIV, caused AIDS, for instance. Plus, in allying himself with Trump, Kennedy had joined forces with the man who’d helped end Roe and spark an uptick in sterilization — to Barnett, a double whammy of women losing agency over their own bodies.

As MAHA turns 1, a fired-up movement is still figuring out how to fulfill its promises

In her apprehension about Kennedy, it was hard not to hear echoes of her take on Vicki Hufnagel, the disgraced doctor whose websites helped Barnett to discover PTLS in the first place: a figure to be wary of, in spite of certain useful ideas. Here’s a man seen as a misinformation machine by many physician groups, making headlines for swimming in sewage-contaminated waters, a lawyer who has no medical license to lose. Some PTLS sufferers hated him; others were too sick to pay much attention. “Our community already faces intense skepticism from the medical system,” Barnett said. “The last thing our advocacy needs is to be undermined by political assumptions or for members to feel alienated over differing views.”

Yet doctors’ skepticism about PTLS drew others to Kennedy. At first, Kenna Kerr took the pain medicines, muscle relaxers, and antidepressants her physicians prescribed. She didn’t attribute her son’s autism to vaccines, because “only crazy people think that.”

“I worked in the medical field. I believed in vaccination. I got flu shots. We made sure all of us did,” she said. It was the reaction to her illness that converted her. “When I brought up PTLS to one doctor after another, they told me there’s no such thing. I pretty much had to stop talking to them because it’s like, OK, you’re getting me nowhere, you’re getting me no help, you’re pushing medication on me but I’m not getting better, I’m getting worse.”

Her fallopian tubes had been removed entirely, so she wasn’t a candidate for reversal, but she flew from Arizona to California to have the stumps reopened. Her symptoms dissipated — and she started to believe that Kennedy had a point in worrying about chemicals in the food supply and in embracing debunked notions about vaccines. She sobs at the link she sees between the immunizations she gave her children and her son’s autism. “What I went through with my sickness, how crap the treatment was through the medical system, it’s like my eyes opened,” she said.

In dismissing people’s pain, American medicine has helped usher in a kind of defensive dismissal, patients brushing away the entire edifice that doctors represent. The medical literature is clear: Again and again, studies have shown that vaccines do not cause autism. When PTLS patient Stacey Underwood was asked about all of that evidence, she said, “I just think that a lot of doctors are closed-minded. I was discredited for years because of the symptoms that I was having.” She believes that people with bad reactions to vaccines face the same disbelief. But if her symptoms weren’t real, how was it possible that she could get a reversal and see the vast majority of them disappear?

Charles Monteith performs a reversal surgery.Eric Boodman/STAT

Charles Monteith performs a reversal surgery.Eric Boodman/STAT

‘I may not be able to repair this side’

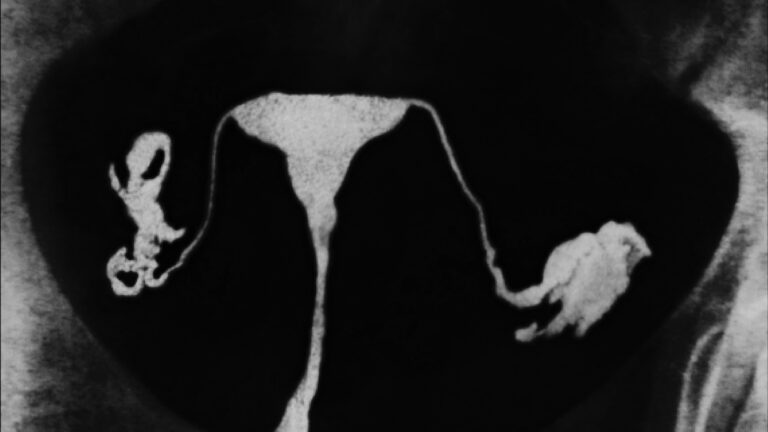

Monteith peered into Bordelon’s abdominal cavity. Usually, he is focused but relaxed in the operating room, chatting, joking, like a performer backstage at a show. But now, his voice took on an edge of seriousness. “She has adhesions to this tube that are pretty dense. I may not be able to repair this side,” he said.

He was about 30 minutes into her surgery. She was draped and anesthetized, the only part visible a tiny bit of skin framing a red hole. He’d sliced through her belly, separating layers of fat and muscle, an assistant widening the sides of the incision with a sort of metallic shoehorn. The right tube had been easy enough. It looked a bit like an earthworm as he maneuvered it — at once robust and pliable, squishier than you might expect for the passageway where egg had met sperm, forming a single cell that had then traveled down into her uterus, becoming an embryo, and, eventually, a child.

He’d found the two severed ends and snipped them open where they’d scarred shut, inserting a temporary stent into one side to keep it wide as he worked. Then he’d begun suturing — first, a stitch to hold the segments close, so that they could be sewn together as if merely mending a wound. He’d tweezered out the stent and put the finishing touches on the seam. “The tube is repaired,” he’d announced. “Now we just have to hope it heals open.”

Her left side was more complicated. The tube and uterus were webbed with stringy tissue, gleaming pinkish in the lights of the operating room. These were bits of the apron that covers the abdominal cavity, made sticky in the scarring after her four C-sections. “Like wallpaper glued to a wall,” Monteith said.

He touched the webbing with a gloved hand. “I could take this down, but the deeper I go, the more chance we could have bleeding. I may get all this off, and find the tube is crap, so to speak, and I’ve done it for no reason,” he said. “I’m not trying to push it, we’ve repaired the right tube, it’s in really good shape.” By his own count, he’d only had to send one patient to the hospital because of complications in the last 10 years. He didn’t want Bordelon to be his second.

Sign up for Daily Recap

All the health and medical news you need today, in one email

He’d had patients get pregnant after reconnecting only one tube. What that might mean for Bordelon’s symptoms was hard to say. She’d hardly talked about her pain in the pre-op appointment.

It didn’t seem worth it. He’d just made the announcement to the team, so they could amend the operative note, to specify that the surgery was no longer bilateral — “I’m not going to repair the left side. So this is going to be a right tubo-tubal anastomosis” — when he slipped a finger under the mat of pinkish stuff. Maybe it wasn’t as bad as he’d thought. In fact, that was something he could safely cut. He started in, the electrical scalpel giving off the strange plasticky smell of burnt flesh.

He began to chat again. “This helps restore her sense of fertility and of being a woman,” he said, as he reached deep inside her abdomen with pincers, threading sutures in and out, in and out. “Trying to have a child with him the natural way, as opposed to IVF, which is definitely more of a —”

He stopped himself. “Well, this is a process. I mean, this is surgery. I’m not kidding anybody.”

His suturing was nearly done. “Stent’s out,” he said, and the whole team answered in a chorus, “Stent’s out,” their way of check-listing every piece that went in, to make sure nothing foreign got accidentally left inside her body. He pulled taut a few last, delicate stitches — fine as the hairs on your forearm, the difference between a severed tube and, hopefully, a functional one — and then was ready to start closing her up.

Can tubal reversal help with symptoms after sterilization?

Would this work? In terms of restoring her fertility, the answer was uncertain, but the uncertainty had been officially clocked, pregnancy and live birth rates tabulated, separated out by age and sterilization method and reversal technique, bounded with error bars — the predictable unpredictability that medical science is built on. In terms of treating her pain, the uncertainty was anecdotal. Of the PTLS Facebook group members who receive reversals, Barnett said, “I don’t have any data to back this up, but if I were to give it a number, I would say 98% of them either improve completely or vastly improve — more than half of their symptoms go away.”

Why this might be was as mysterious as the biology of PTLS itself. Different phenomena might be at play in different bodies, but could present in a similar way. “We know so little about pain, and it can be so multifactorial, especially in the pelvis, where there’s a lot going on, and women’s pelvic pain is just such an understudied thing,” said Kavita Arora, an OB-GYN at the University of North Carolina and a sterilization researcher.

To her, some of that pain might have to do with women stopping birth control and their periods returning after a long hiatus. Barnett, though, points out that many with PTLS weren’t on birth control. Some scientists have wondered whether sterilization might disrupt tiny blood vessels, shifting both blood flow to the ovary and its production of hormones. But the data are mixed, with some studies suggesting there is an impact and others suggesting there isn’t. Why yet more surgery might help is unclear.

Or it might have to do with what is known as retrograde menstruation: the idea that during menstruation, when blood flows out of the uterus through the cervix and vagina, some also goes through the passage of the fallopian tubes and out into the pelvic cavity. “When those passageways are blocked, it makes sense that there’s probably some pain and cramping there,” said Arora.

Then again, in about half of Monteith’s patients who report these symptoms, he sees the tubal ligation site studded with buckshot-like dark patches: a classic sign of endometriosis. It’s a common and mysterious diagnosis, often thought to be caused by retrograde menstruation, those bits of blood and uterine debris triggering inflammation and terrible pain. In theory, blocking retrograde menstruation could help prevent this — but it’s possible that in some cases, something about sterilization might open an accidental fistula, a fissure in the uterine wall, allowing that tissue to escape and settle where Monteith finds it on reversal. But endometriosis wasn’t present in everyone. Bordelon, for instance, had none.

Ditto for surgical clips. A rare inflammatory backlash might explain some aspect of reversal: Removing the object the body’s reacting to might truncate the reaction. But why then would someone like Bordelon, whose tubes had been severed — no clips involved — experience PTLS, too? And why would those who’d had their clips removed but not reversals find less relief than those who’d gotten both, as Barnett has observed in her group?

For some patients, the symbolism of reversal is explanation enough, the rejoining of what has been severed. Some doctors, meanwhile, couldn’t help but wonder whether the placebo effect was sometimes involved. The literature describes a strange phenomenon: the more intensive a treatment, the better patients seem to feel. One study found that four daily sugar pills were associated with better ulcer healing than two. Injecting saline was better at treating migraine and hypertension than oral pseudo-medication. Sham surgery has been found to help with everything from torn knee cartilage to Parkinson’s disease. This might be at play in some PTLS patients, the intensity of the surgery itself therapeutic.

Barnett rejects this idea. To her, it sounds dangerously close to labeling the syndrome psychosomatic. Yet those who study the brain circuitry involved in sham therapies disagree. “There’s no question that patients with Parkinson’s disease have a real illness,” said Matthew Burke, a cognitive neurologist and placebo effect researcher at the University of Toronto, who emphasized that he has no expertise in gynecology or PTLS. “But Parkinson’s patients are exquisitely placebo-responsive.”

In Barnett’s thinking, physicians don’t need any more excuses for not studying PTLS. She’s been dismayed to see the Trump administration slashing scientific funding: She wants scientists to keep delving into her condition, exploring its immunological, hormonal, and genetic characteristics. “I challenge them to look at our group specifically. This could be a great pool to figure out some questions that we’ve not ever had the answers to,” she said.

Even those who in some ways are aligned don’t see eye to eye on everything. Monteith, whom Barnett considers an ally, isn’t sure about describing this group of patients as having a “syndrome.” That they have symptoms, however, is uncontroversial; to pretend otherwise feels untenable and unhelpful — a fact that you can’t dispute.

Gentry and Bordelon at their home in Marksville.Emily Kask for STAT

Gentry and Bordelon at their home in Marksville.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon holds up an ultrasound of her expected twins.Emily Kask for STAT

Bordelon holds up an ultrasound of her expected twins.Emily Kask for STAT

A pregnancy, and a greater vigilance

Bordelon and Gentry planned their wedding around the Monteith miracle they were hoping for. Too soon, and she’d be recovering from surgery, too far out, and she might not fit into her dress, or might be at the sleepless, unceremonious whims of a newborn. “We’d both already been married, we’d both already had the big old wedding with the reception and all that other stuff,” Bordelon said. This time, they’d keep it simple, just their families and a few friends at the bridge in City Park in New Orleans, surrounded by sweeping palms and cypresses. They picked a date in March.

Not long before, she discovered she was pregnant. Part of her was nervous: She knew that tubal reversal came with a higher risk of the embryo catching and implanting in the newly sutured tube, and she wanted to rule that out as soon as possible, before it became an emergency. But she was excited, too. At the wedding, she handed Gentry a gift bag, with the positive test in it, and a onesie that read “Baby Gentry.” He cried. A band paraded them down Bourbon Street. They ate nachos at the Hard Rock Cafe. Then, they went back to Marksville, Gentry back to drill shafts, Bordelon back to nursing shifts.

The pregnancy wasn’t ectopic: The ultrasounds showed it clearly in the uterus, not just one fetus, but two. She had not only dodged the risks of tubes healing closed and embryos implanting in the wrong place, but also, as far as she could tell, fixed her PTLS. She’d only had a handful of menstrual cycles before her periods stopped, but they’d involved none of the terrible pain she’d come to expect. She wasn’t sure what the problem was, biologically, but she figured it had to be related to her tube-tying: She’d never had issues before sterilization, they’d appeared right afterwards and then stopped once the surgery was reversed.

The ordeal hadn’t turned Bordelon off mainstream medicine the way it had for some. Bordelon still trusted the data showing that vaccines were protective. She showed up for her prenatal appointments. But she was warier, less willing to take what physicians said and did at face value. To her, there’d been a lack of communication before her tubal ligation. If she’d known about PTLS, she probably still would have gotten the procedure; it was the disempowerment that rankled. “Since it wasn’t explained, I feel like that choice was taken away from me,” she said.

She didn’t want anything like that happening with her twins. She got a bad feeling from her old obstetrician, who provided medicine as if it were rote, the appointments conveyor-belt like, in and out in 10 minutes, with little time for discussion. “They just didn’t really seem concerned that it was twins, and that made me feel a little iffy, because it should have been high-risk pregnancy,” she said. She changed OBs.

The shift in her was subtle: not mistrust on a grand scale, but a greater vigilance. “I’ll ask more questions — Is it necessary? What’s better for the babies? — rather than just going with my doctor’s first response.”

Once she began to show, word got around. She was pregnant again after a tubal. Other moms started calling, wanting to know the details, wondering if this was something they could pursue themselves. Often, that wasn’t just because they wanted another child. By her count, she heard from five people who’d been having similar symptoms.

She remembers one night in particular, waiting for her daughter to emerge from an elementary school dance, chatting with a group of women and discovering that a few of them also had this condition that doctors couldn’t seem to explain or dispel. From a distance, it seemed like a pleasant evening — cool, by Louisiana standards, chilly enough for a 9-year-old to wear jeans, parents conversing in the foyer with strains of Kidz Bop and kids’ voices filtering from the gym — but lean in close enough and you’d hear an undercurrent of pain.