In 1968 a mysterious man arrived in New Zealand and soon after was promising a miracle cancer cure. He charmed patients, health practitioners and journalists alike. And when he was chased out of the country in 1977, he took his ‘treatment’ elsewhere, to new islands and new patients. Tasha Black digs through the archives and speaks to family members still feeling the effects of New Zealand’s greatest conman, Milan Brych.

A doctor is injecting his patients with a mysterious yellow liquid. No one knows what’s in the liquid. But the doctor is charming. He bedazzles patients with his intelligence, kindness, and empathy. Patients adore him. Many of them are dying from cancer and they believe the doctor, and his mystery injections, is their last hope, their last chance for a miracle. Desperate cancer patients travel from as far away as the United States and Australia to seek out the renowned doctor. There is just one problem: he’s a fake.

This is the almost unbelievable story of Vlastimil “Milan” Brych. A man who left a trail of destruction around the world, from the 1970s and decades beyond, with side effects still felt today. Brych could be New Zealand’s greatest conman, and yet was never prosecuted. He left the country in 1977 and took his scam treatments to other countries before disappearing forever.

Cancer is a frightening thing. In the early 1970s, it was likened to a death sentence with limited treatment options. So, in 1972, when a doctor at Auckland Hospital began offering a new treatment – a series of injections based on his research in Europe – the question for terminal cancer patients was why not? What do you have to lose?

Brych (pronounced “brick”) first arrived on New Zealand shores in 1968 as a 28-year-old refugee from Czechoslovakia. He settled in Auckland and quickly found employment as a laboratory assistant at Auckland Hospital. In 1972 he was granted full registration as a doctor with the Medical Council and before long, Brych was working in the department of radiotherapy, treating cancer patients. In mid-1972, Brych went public with his claims of a potential new cancer treatment. Patients loved the foreign doctor. Brych had a caring, if unorthodox, bedside manner. The New Zealand Listener reported in 1974 that Brych would take his patients’ hands and stare silently in their eyes. “Brych does seem every patient’s dream of a romantic doctor,” the magazine wrote.

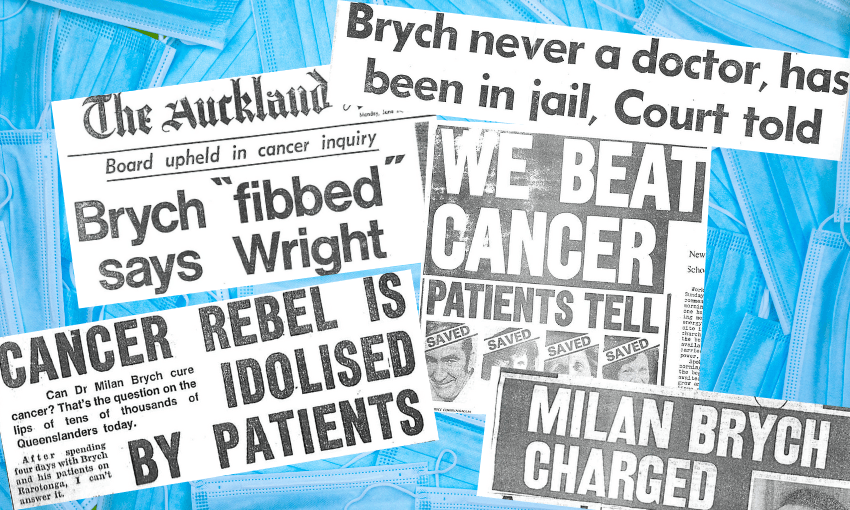

The media fawned over Brych. They were enamoured by the charismatic young doctor and his potential cure for cancer. Newspaper headlines screamed: THE DOCTOR THEY CALL GOD and CANCER VICTIMS SAVED. Brych peppered his speech with medical terminology and spoke with such assured confidence it was hard to doubt the man.

In the 1970s, New Zealand’s medical system was hierarchical and conservative. Too stuffy, some felt. And now here was Brych, challenging the status quo. He wore flamboyant shirts, was a smooth talker, and offered what all patients seek: hope. Brych was the ultimate underdog fighting against the establishment. The debate over Brych and his cancer treatment played out publicly in newspapers, radio, and television news. Brych was notoriously cagey about what his treatment actually was, but patients and staff reported injections of yellow liquid.

Pressure was building and in 1974 the Auckland Hospital Board undertook a study into Brych’s patients. They found his treatment results were “no better, no worse” than conventional cancer treatments, but patients had been treated with supplementary additives, the nature of which was unknown. Only a decade earlier the drug thalidomide, used to treat morning sickness, was revealed to have caused severe birth defects in babies.

While the media loved the story of the flamboyant hero doctor, not everyone was so convinced. When Philip “John” Scott (later Sir), a young doctor with a steely commitment to scientific truth, first encountered Brych in the hospital wards, he was troubled. According to an interview with Dr Scott in the 2012 TV documentary Cancerman: The Milan Brych Affair, Brych claimed to have sent blood samples away to the laboratory, but when Dr Scott called the lab, he discovered no such request had been made.

Brych had been caught out in a brazen lie, kicking off a decades-long dogged search for the truth by Dr Scott. While other colleagues excused Brych’s lack of medical knowledge with the belief that medical training in eastern Europe was of a lower standard, and Brych was still mastering English, Dr Scott was less forgiving and far more suspicious. He questioned why Brych never disclosed specifics of his treatment and why his patient notes were so poor. Scott’s daughter Philippa, speaking to The Spinoff said, “[My father] thought right from the start that [Brych] was lying, there was something wrong, something dodgy about this new doctor, that if he had this fantastic treatment he should have been making notes of it on each patient.”

In 1974 an Inquiry into Cancer Services at Auckland Hospital was launched. Brych’s supporters came out in droves, turning up to the Auckland Town Hall to fervently defend him. Patients spoke passionately of Brych’s miracle cures and jeered at anyone who spoke against him. During the inquiry Brych refused to answer some questions, which in turn “made him an increasingly mysterious and, inevitably, glamorous figure,” wrote The New Zealand Listener.

Meanwhile, Scott and his family began to receive mysterious and dangerous threats. Phillippa remembers their home was broken into. A bomb was left in the letterbox, which turned out to be a fake. Police provided surveillance. It has never been proven who was behind the threats.

The inquiry into cancer services concluded and the findings were laid bare: Brych was a liar, caught “professionally fibbing”. Brych’s employment was terminated at Auckland Hospital and he was given three months’ notice. Brych’s behaviour during the inquiry, particularly his poorly worded answers to medical questions, left Scott wondering: was Brych even a real doctor?

Brych claimed to have lost his medical qualification papers when he fled Czechoslovakia. So Scott travelled to eastern Europe – behind the Iron Curtain – in search of answers. And he found them. In late 1958, Brych had attacked a shopkeeper with a hammer and served seven years in prison. This was the time Brych claimed to be studying medicine. No record was ever found of Brych’s medical qualification. Brych countered these claims, saying Czechoslovakian authorities were attempting to discredit him as a political refugee.

In 1974, Brych was deregistered by the Medical Council meaning he could not practice medicine. However, Brych immediately appealed the decision at the Supreme Court, and while the appeal was pending, Brych’s name was reinstated and he continued to treat cancer patients, now at the Adventist Hospital and Glenelg Private Hospital in Auckland. Legal proceedings dragged on for three years, and then in early 1977, shortly after the court date for hearing the appeal was announced, Brych abruptly dropped his appeal.

Behind the scenes, Brych had been plotting his next move. He had a knack for befriending politicians, including Albert Henry (later Sir), the first Premier of the Cook Islands. The two came to an agreement: Brych was permitted to set up a cancer clinic at Rarotonga Hospital if he also headed up an institute to study traditional Polynesian medicine.

THE PATIENTS

Media coverage of Brych’s treatment had rippled across the sea, and Australians were taking notice, including a young couple from Perth. Debbie Harris was 16 years old in 1977, and dating Mark Gasiorowski. “We were madly in love, you know how it is,” Debbie says, chuckling. Gasiorowski was fun to be around, forever a joker, but one day he developed a cough. “He joked, ‘Oh, I must have lung cancer,’ and we just laughed it off,” says Harris, now 64 and living in Perth. “But we ended up going to the doctors, and yes, he had lung cancer.”

The prognosis was not good. “Basically, he was told by the doctors they couldn’t do anything for him. He was written off,” she says. But Gasiorowski, who was just 19 years old, was undeterred. He began researching, looking further afield for options. “He had to find something that he was going to do to try and save himself,” says Harris. That’s when he came across media reports of Brych’s clinic in Rarotonga. The treatment was experimental, sure, but it did seem to be showing some remarkable results – one young girl with cancer had reportedly learned to walk again.

Some of the reporting on Brych’s patients

In January 1978, the young couple – now engaged – travelled to Rarotonga. They moved into a beachside unit, Gasiorowski began Brych’s treatment, and they fell into the rhythm of island life. They would ring home on a black Bakelite telephone and write airmail letters. With other cancer patients and their families, they formed a community. Gasiorowski was optimistic. “We never thought for one minute that he wouldn’t come home,” remembers Harris. “You don’t think like that, as silly as it sounds, we were full of hope.”

But Gasiorowski began losing weight. A few months after he arrived, he had a seizure and three days later, on April 6 1978, he died. Repatriating Gasiorowski’s body to Australia wasn’t an option. In the 1970s, commercial flights to and from Rarotonga were infrequent, only every few days. There was no morgue, so Gasiorowski was buried quickly in the tropical heat.

Harris treasures the time she spent with Gasiorowski in Rarotonga, describing it as a beautiful paradise. These days, she has trouble reconciling her experience with what she would later come to learn about Brych. “I think Brych knew that Mark wasn’t going to end up going home. [Brych] said, ‘Oh, we’ll just try one more treatment’, and I think that was probably a money-making exercise when I look back on it now. But obviously, at the time it was like maybe this is the one that gets [Mark] over the edge, and you end up with this miracle cure.”

At the time, Brych’s cancer treatment cost $680 per patient, per four-week period (approximately $5,600 today). Some families remortgaged or sold their homes and spent life savings on the treatment. New Zealand Police would later document that between 1977 and 1978 in Rarotonga, Brych made several lavish overseas trips, spending $26,000 (nearly $200,000 today).

Within the medical fraternity, the tide was turning against Brych. However, a handful of general practitioners in Australia were still referring cancer patients to him.

Nathan Steinkoler, a Jewish immigrant and Melbourne shopkeeper, sought treatment from Brych after he was diagnosed with cancer in 1975. Nathan’s son, Leon, says his father was referred to Brych’s clinic by his doctor. His parents respected doctors and so, based on this advice, they flew to Rarotonga for treatment.

Leon remembers when he heard the news that his father had died. It was the Jewish New Year and Leon was 18 and home alone in Melbourne. “It was forever ago, but almost like yesterday,” he says from his home in Melbourne. The last time Leon had spoken to his mother, the prognosis was positive. “She was really excited because [my father] was doing much, much better,” he remembers. “So, it was a bit of a shock when he died about a week later.” This was a common story with Brych’s cancer patients. They improved and then they died.

Over the years, Leon has come to hold Brych responsible for his father’s death. “I refer to him as the man who murdered my father. He still had 18 months or so to live,” says Leon, tears in his eyes. “Mum and Dad made a really poor choice, but they weren’t informed correctly. No one has apologised.”

I ask Leon what he thinks of Brych today. “I hope he’s burning in hell.”

THE INVESTIGATIONS

In Auckland, 1977, Scott acquired syringes Brych had used and discarded. The syringes were sent off for forensic testing. The results showed traces of steroids, which Scott had predicted, but the main content was procaine, a local anaesthetic which can create euphoric effects. Further research by Scott showed that “almost all” of Brych’s original group of patients in New Zealand were now dead. “Of the other people he treated, we are well aware that many of them never had cancer,” Scott wrote.

So, how did Brych keep slipping past the authorities? New Zealand Police investigated Brych for years. Despite “compelling evidence against Brych” police decided not to prosecute him, mostly based on the fact that Brych was deregistered from New Zealand’s Medical Council and no longer practising in New Zealand, and the cost to fly overseas witnesses, who could help prove Brych never qualified as a doctor, to New Zealand was deemed too high.

New Zealand Police considered extraditing Brych from the Cook Islands but noted it would “inevitably involve consideration of our relationship with the Cook Islands administration and therefore the question becomes a political one.” According to documents released under the Official Information Act, police were sceptical that a New Zealand jury could be unbiased. A trial of Brych “would be clouded by the undoubted emotion aroused by the controversy over both his medical qualifications and his claims to a cancer cure”.

The Cook Islands government invited the New Zealand police to investigate fraudulent administration of Brych’s Rarotonga clinic, from 1977-1978. Police tried to locate records belonging to the trust that oversaw the clinic, but “a number of important records were found to be missing”. Bank records were “destroyed in mysterious circumstances”. Customs records to ascertain what drugs the trust had imported, were also missing. Police enquired about the “supposedly secret preparation” that was injected into patients. According to the files, no one spoken to could or would describe what this was. “Doctor [redacted] states he knew but was sworn to secrecy. Doctor [redacted] thought it was a steroid and thus nothing unusual.”

In 1978 the Cook Islands premier resigned and the incoming premier made it clear Brych was not welcome. Brych left Rarotonga abruptly, leaving his patients in the lurch, but not without a pocketful of cash for himself. In just over a year, cancer patients in Rarotonga had paid Brych’s private practice more than $600,000 (nearly $5 million today) in patient fees. Brych paid no tax on his earnings and is alleged to have left the Cook Islands with a forged tax reference.

Brych fled to Los Angeles where media soon reported he was driving a Rolls-Royce and living in luxury. Before long, Brych returned to his ways, finding work in a cancer clinic. One day, in 1980, a man entered the clinic describing cancer symptoms. Brych quickly diagnosed him with cancer, but unbeknownst to Brych the man was an undercover agent and just as Brych was offering him treatment, the agent arrested Brych. Charges were laid against Brych, including practicing medicine without a license and fraudulently providing cancer treatment. Brych pleaded not guilty.

Once more, Brych’s supporters rallied, even travelling from New Zealand to Los Angeles to testify, fervent in their belief Brych was a maligned genius. Scott also travelled to Los Angeles to testify for the prosecution, but the underlying threat to his family had not gone away, with unannounced visitors at the house and numerous incidents. Scott’s daughter Philippa remembers, tearfully, being concerned for her mum’s safety. “I remember… just feeling so sad for my mum, she was on her own and had to put up with that.” Phillippa believes Brych’s supporters were trying to scare the family – a torment that lasted decades. “I can think about it rationally, but the actual feelings, the fears, they stay with you, that you felt as a child,” she says.

The drugs Brych was using to treat cancer at the Los Angeles clinic were analysed and found to include a cheap drug commonly used in chemotherapy and, at the time, worth about USD$10 per vial. Brych was charging patients USD$9,600 per injection. Brych was found guilty on 12 charges, including medical malpractice and grand theft by false pretences. The judge described Brych as a callous, devious, and cunning human being. To Scott’s relief, the Americans achieved what New Zealand never could: they put Brych behind bars.

THE CEMETERY

In Rarotonga a gentle sea breeze rustles through the coconut trees. The afternoon sun beats down on Cate Walker as she sweeps and cleans graves at Nikao Cemetery. She is tanned from hours spent tending to the dead. Walker loves cemeteries. She has restored countless gravestones near her home in Queensland, Australia. But her passion for cemeteries stems from a place of pain: Walker’s mother is buried at Nikao Cemetery. Gloria Walker, a primary school teacher, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1976 and was treated by Brych the following year in Rarotonga. She is one of 65 foreign nationals buried there between April 1977 and August 1978. All were under Brych’s care. It’s a staggering number for a nation with fewer than 18,000 residents at the time. Most were Australian, but there were a handful of American, British and New Zealanders. At the time, news reports show locals were concerned their island was gaining a reputation as a place to die. The cemetery was nicknamed the Brych-yard.

In 2014, on a visit to the cemetery, Walker was dismayed. It was wildly overgrown, headstones were crumbling, and graves were washing into the lagoon and out to sea, including the coffin and remains of Debbie Harris’s fiancé Mark. “The cemetery was just a disaster zone,” says Walker. “I said, ‘I’m going to do something about this now. This is wrong.’” And she did. Walker petitioned politicians in the Cook Islands, New Zealand and Australia for support and in early 2016, the Cook Islands government began constructing a rock sea wall to protect the cemetery. After years of Walker’s advocacy, and support from local volunteers in Rarotonga to help maintain the grounds, the Cook Islands Investment Corporation announced earlier this year, it would manage and maintain the cemetery.

Cate Walker at her mother’s grave in Rarotonga

Cate Walker at her mother’s grave in Rarotonga

Walker runs a Facebook page for Nikao Cemetery and has connected with most of the families of cancer patients buried in Rarotonga. Some families, after making initial contact via the Facebook page, stopped talking to her after they realised she is anti-Brych. But Walker is pragmatic. “It’s very difficult to accept that you were scammed by a fraudster, someone who was a very, very clever conman,” she says.

Walker’s mother Gloria died on Easter Sunday, 1978. Cate was just 13 years old and staying in boarding school in Queensland. Walker is angry she missed the last four and a half months of her mother’s life, particularly at a critical time in her own life, as a young teenager. She has letters written by her mother while receiving treatment in Rarotonga, describing a lack of pain medication being administered. “It’s horrible to think that my mother died in pain, a long way from home.” Now in her sixties, Walker has had time to reflect. “I feel let down by a lot of people. New Zealand should have stopped Brych.”

SEARCHING FOR BRYCH

Brych served three years of his six-year prison sentence in the United States. On his release in 1986, the question was, where would he go next? He couldn’t practice in New Zealand; an Australian Immigration Department spokesman told the press that if Brych found himself in Australia he would be “hunted, prosecuted and thrown out”. After a luxury holiday in Tahiti with his third wife, reported on by media, Brych’s whereabouts becomes murky. And so began hours of researching, digging through old newspaper clippings, and searching social media profiles to find the current whereabouts of Milan Brych.

In the late nineties, Brych’s name popped up in Europe. According to news reports, a Swiss company called Telmat was selling two herbal products invented by none other than Brych. The products, named Vectorex and Scalarex, were marketed as “harmless”. That is until European health authorities were alerted that the herbal products, marketed as natural, allegedly contained corticosteroids – anti-inflammatory medicines used to treat a range of conditions, from asthma to lupus. This led multiple European countries, including Germany, France, and Switzerland to issue public warnings and ban the unauthorised distribution of the products.

After this, reports of Brych faded away. But he never disappeared, he just changed his name. Brych created a new identity for himself in the United Kingdom. In 2002 he married Swiss woman Heidi de Sepibus-Voegeli in Oxfordshire, England and he began to go by the name John de Sepibus-Smith. Under this new name, Brych and de Sepibus-Voegeli established multiple UK companies in the early 2000s, with medical-sounding names, such as Oxford Centre of Molecular Immunology. There is scant information about what any of these companies actually did. What little information available is on alternative health forums promoting the use of unregulated treatments. Brych’s new name is dropped in online posts, such as Dr. John de Sepibus Smith, professor emeritus of the University of Oxford.

In 2022, a Czech man wrote a blog post about being treated by one Professor De Sepibus-Smith in 2005 for severe gastrointestinal issues. Over dinner in the Czech town Litomyšl, he tells me that he visited the professor at his “mansion” in Beaulieu-sur-Mer on the French Riviera. The professor was a “very successful businessman” who funded his own research, he said.

I explained to him that “Doctor” De Sepibus-Smith was a man named Milan Brych, who was never a real doctor, and that he had been imprisoned for fraud. I sensed the Czech man was reluctant to believe me, but when he watched archival footage of Brych, he conceded that he believed it was the same person. He couldn’t recall the details of his treatment, except that it involved injections.

DIFFICULT QUESTIONS

Brych supporters argue that most of his patients had terminal cancer – they were going to die anyway, and Brych gave them hope. It’s true, Brych did offer people a brief glimpse of hope. But in the case of his Rarotonga clinic, Brych encouraged patients away from their homes and from their families, only for them to die and be buried 5,000km away. Leon Steinkoler is still pained at the missed opportunity to spend time with his father Nathan before he died. Leon believes he may have missed deathbed conversations with his father, including about his father’s experience surviving Auschwitz.

Then there’s the money. Brych’s patients handed over thousands of dollars, even selling family homes to pay for treatment.

It wasn’t just patients and loved ones that were taken in by Brych, it was politicians, doctors and journalists. Authorities quite literally took Brych at his word. The nation fell for Brych’s charm, his twinkly eyes and knowing grin. Brych was provocative, he pulled people into his orbit, and gave the media what they wanted. He was clickbait before the term existed.

LASTING EFFECTS

The ripple effects of Brych’s lies run deep. Decades on, families are still processing. Loved ones continue to make the pilgrimage to Nikao Cemetery in Rarotonga. Walker has worked tirelessly connecting families to gravesites. Those who lost loved ones find peace in the restoration work and the friendships formed through the Nikao Cemetery community. “Cate is a dynamo. I applaud her for everything she’s done, she’s done so much good,” says Leon.

In 1988, Scott was knighted for his services to medicine. He died in 2015 aged 84. Not only did he risk his own professional career, but it also took a “huge toll” on him, says his daughter. “It was really, really hard for him. It would have been a lot easier just to stop, just to give up.” But ultimately, he wouldn’t stand for a charlatan and a con artist. “I am proud of my father, his tenacity and following up what he thought was right. He believed in medicine, he believed in science,” says Philippa.

If Brych is still alive, he would be 85. But the story of New Zealand’s greatest conman may be over. At that restaurant table in Litomyšl, the Czech man told me that he heard “Professor de Sepibus-Smith” had died suddenly from an aortic rupture, likely between 2015 and 2018. His research, apparently, died with him.

There have been other fraud cases involving New Zealanders or those working in New Zealand healthcare. Fake psychiatrist Linda Astor tricked authorities to become head of clinical psychiatry at Nelson-Marlborough Health in 1997; Mohamed Shakeel Siddiqui used another person’s psychiatry qualifications to work for Waikato District Health Board in 2015; Zholia Alemi forged an Auckland University medical degree in 1995 and posed as a psychiatrist working in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service for two decades; and in 2022 Yuvaraj Krishnan faked his medical qualifications to work at Auckland’s Middlemore Hospital.

We may never know how many people Brych treated, but it could be in the thousands – spanning decades, from New Zealand, to the Cook Islands, Los Angeles and Europe. Brych’s influence was widespread. My own nana blended apricot kernels in a smoothie after she heard Brych promote the idea as a means to prevent cancer. The apricot theory is widely disproven, and even harmful – apricot kernels are toxic.

Even today, there are people who still support Brych, and believe he was a genius before his time. In reality, Brych was an expert manipulator, a serial liar who spun circles around people. He was almost always one step ahead, leaving town overnight to evade authorities and reinvent himself elsewhere. He had a violent streak bubbling below the surface. He took a hammer to a shopkeeper. He fleeced desperate people of their money. And he manipulated until the very end. Brych’s work was a human experimentation. There is not one written public record or publication in any scientific journal of Brych’s so-called cure. In the words of Scott, who knew all along, “there never was any miracle.”