Opinion: We might think of air pollution as a problem for other places: the smog-shrouded skylines of Asian megacities, or California’s gridlocked freeways and wildfire haze.

In Aotearoa, where sea breezes sweep across coastal cities and skies seem clean, it’s easy to assume our air is among the world’s purest.

In reality, it’s one of the largest public health problems facing the country.

The Our Air 2024 report from the Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ estimates that air pollution contributes to more than 3200 premature deaths and 13,000 hospitalisations annually, and about $15 billion in social costs.

Motor vehicles account for most of the harm, followed by domestic fires, especially in colder regions.

“We’re talking vehicle exhaust and home heating – wood burning and coal burning are the largest environmental contributors to health [problems] here in the country,” says Dr Joel Rindelaub, a senior lecturer in the School of Chemical Sciences at the University of Auckland.

Those emissions generate a range of pollutants: gases including nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide, but also fine particles known as PM2.5, which are so small they can slip deep into the lungs, bloodstream, and even the brain.

Measurements show that urban centres in New Zealand record higher concentrations of black carbon – the sooty residue from incomplete combustion – than comparable cities in Europe or North America. And rural towns aren’t immune.

“Some of the worst air quality across the motu is in our rural locations, specifically like Central Otago, where during wintertime we’re burning a lot of solid fuel for heat,” Rindelaub says.

“The topography there creates what’s known as an inversion layer – basically, it puts a lid on the air, keeping it there and letting concentrations of pollution build up to dangerous levels.”

Rindelaub’s research shows air pollution peaks in winter, and it’s often the smoke from chimneys driving those spikes.

This is concerning because, though people enjoy the smell of wood fires and beach bonfires, the smoke they produce contains a high number of carcinogenic chemicals.

Motorways add another burden.

“Transport corridors are going to have higher concentrations of the two things that current mortality rates and estimations are based off – nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter.”

In all, he says air pollution leads to more premature deaths annually than diabetes, colon cancer, melanoma and road accidents combined.

“It’s the largest environmental threat to human health.”

Understanding the risk

Rindelaub’s team has been investigating air quality in Auckland neighbourhoods over recent years and has found some concerning trends.

In winter, for instance, the researchers recorded high concentrations of arsenic, a carcinogen.

Though tracking where pollutants come from is complex, every combustion source leaves its own signature.

“Anytime you’re having combustion events, you’re going to be creating bad things,” he says.

“But we can look at wind directions and air parcel back trajectories, and chemical composition can be indicative for a certain type of source.

“Shipping emissions, for instance, might have an increase in elements like vanadium, which would be unique to them.”

The Our Air 2024 report also highlights wide inequalities in exposure, with Māori, Pacific peoples and lower-income communities breathing the dirtiest air, especially near busy roads or industrial areas.

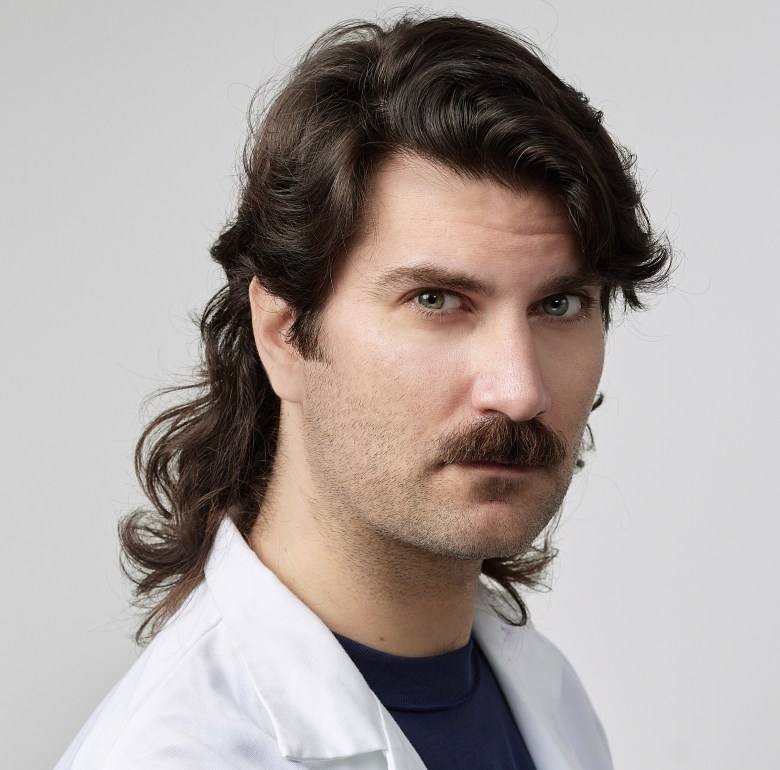

Dr Joel Rindelaub, atmospheric chemist at the University of Auckland, says air pollution remains one of Aotearoa’s biggest and most underestimated environmental health threats. Photo: Joel Rindelaub

Dr Joel Rindelaub, atmospheric chemist at the University of Auckland, says air pollution remains one of Aotearoa’s biggest and most underestimated environmental health threats. Photo: Joel Rindelaub

That pattern was reinforced by recent research led by the University of Canterbury, which found that children born in deprived neighbourhoods grew up in significantly dirtier air: a disparity likely to carry lasting health effects.

This, Rindelaub says, only strengthens the case for better monitoring and tougher standards.

“Absolutely, we need to be gathering more data. It’s imperative for the health and safety of the country.”

Air pollution and climate change are linked by the same root cause: burning fuels.

“When we think about combustion events, we’re creating harm in both categories – things that are negatively affecting our health as well as negatively affecting the planet.”

And as the planet warms, the feedback loop will worsen.

“With increased temperatures, we’re going to have more inclement weather. We’re also going to have an increased risk of things like forest fires – and these major events are going to increase in frequency as the troposphere warms.”

Hotter, drier years are also known to drive up energy demand – and hence more combustion.

The case for controls

For Rindelaub, the single biggest fix would address the lack of PM2.5 regulation in New Zealand.

The US has regulated it since 1997, the European Union since 2008, and China since 2013.

“And this is the type of air pollution that we know can lead to premature death, lung disease, heart disease, as well as impacts on cognitive health,” he said.

Rindelaub points to research showing that people living near motorways are more likely to develop dementia.

“People that live in areas with increased air pollution have reduced measures of intelligence and can also be associated with increased risks of schizophrenia, bipolar and personality disorders and depression – but the biggest concerns are on the developing brain.”

Even short-term exposure, he adds, can harm fetal and infant development.

“We need to regulate PM2.5 specifically. We need greater controls and the cost-to-benefit ratio of putting in these controls is a massive victory. It’s a huge win.”

He noted that, in the US alone, an annual 239,000 early deaths are estimated to be saved by PM2.5 controls.

“In China, in the four years after implementing their PM2.5 controls, they estimated that over 42,000 premature deaths were prevented and more than 700,000 years of life saved.”

Here, he says, the benefit-cost ratio would be about 8.4 to 1.

“For every one dollar spent, we’re getting $8.40 in savings – easing healthcare costs and days of work lost.

“It’s shown in numerous countries across the world that if you implement air-quality regulations, people are healthier and your economy is better. It’s an easy saving.”

If there’s one misconception that frustrates Rindelaub, it’s that people equate regulation with ‘red tape’.

“Sometimes when we hear the term regulation, it doesn’t sit well. There’s a lot of negative connotations. But when it comes to air quality, these aren’t regulations.

“This is literally an investment into New Zealand, and so the return-on-investment on this is huge. It would benefit everyone.”

The other misconception is more subtle: the assumption that if we can’t see the pollution, it must not exist.

“Air pollution can be invisible to the eye, so it can still be present even if we can’t see it,” he says.

“And when we think air pollution, we first think about lung or maybe heart issues, but we also need to recognise that air pollution affects the brain – which turns out to have massive impacts.

“By not addressing air pollution, we could literally be making ourselves dumber.”

The world is facing unprecedented environmental challenges. Planetary Solutions, an initiative of the Sustainability Hub at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, and Newsroom, explores these issues — and the practical ways we can all be part of the solution.