Earlier this month, Harriet Wild was struck by the sheer volume and interconnectedness of stories reflecting the drivers and determinants of mental illness, its societal impacts, and the gaps in treatment. She explains.

As the pressure on the health system continues unabated, there is rarely a day without a health story in the media, because public interest is so acute. Hospitals and healthcare are the second-highest concern for New Zealanders behind inflation and the cost of living.

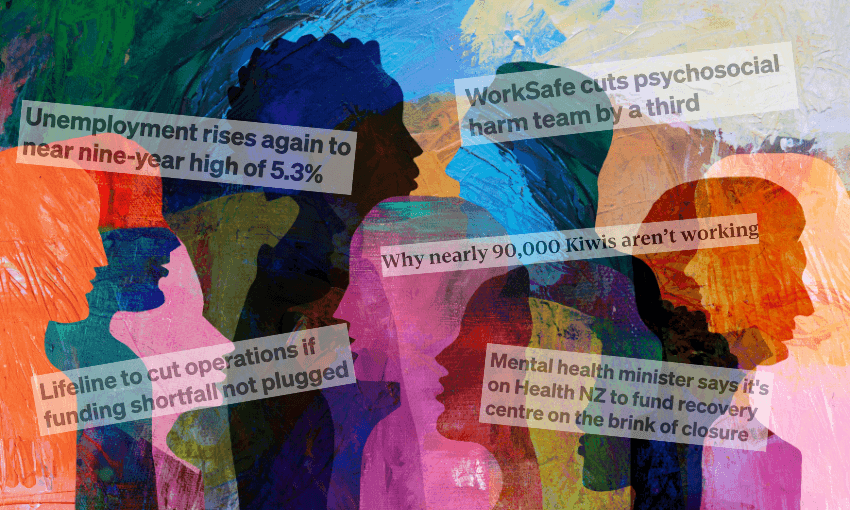

What struck me, however, was the sheer volume and inter-connectedness of stories in the week of November 3-7.

For ASMS (Association of Salaried Medical Professionals), these stories reflected the drivers and determinants of mental illness, its societal impacts, and the gaps in treatment risked by the lack of or the imminent loss of services. They also reflect the findings of one of our recent research papers, Managed Decline: The Health of New Zealand 2011-2024, by ASMS economist Andrea Black.

Managed Decline examines nearly 15 years of data in response to the self-rated health question from the annual New Zealand Health Survey (NZHS). How we interpret our own health and wellbeing is important – and is relatively well-correlated to mortality data.

Our health is deteriorating. Our population, particularly people of working age (15-64 years) were in worse self-reported health in 2023/24 than in 2011/12.

Self-reported “excellent” health – which could be closely aligned to the WHO definition of health – declined 45%, from 21.3% of adults 15-64 years in 2011/12 to just 11.8% of adults in 2023/24.

For people over 65 years, “excellent” health declined 25% between 2011/12 and 2023/24.

Self-reported “fair” health increased 54% for people under 65, while for people over 65 it was broadly unchanged (12.1%-12.3%).

Women more likely to rate their health as “fair” or “poor” compared to men (15.8% versus 12.9%), with wāhine Māori (24.6%) and Pacific women (20.1%) also overrepresented in “fair” and “poor” health.

The increase in “fair” health for working-age people is likely due to social, economic and environmental determinants of health, including housing, income and employment.

On November 3, RNZ reported that ACC funding would cease for Whakamātūtū, the Depression Recovery Centre in Wellington. One client said the service has “given me that connection back to the community and is a huge stepping stone for me to return to the workforce”. The loss of this service echoes the closure of Rauaroha Segar House in Tāmaki Makaurau in September.

November 4 – joblessness and mental distress

A decline in health – including mental health – can mean an exit from the workforce. Stuff’s Bridie Witton reported on November 4 that nearly 90,000 people rely on a benefit due to mental distress – the single-largest health-related reason.

Some of the increase in “fair” health could be attributed to the significant increase in levels of psychological distress. This is pronounced among working-age people, compared to people over 65.

Psychosocial harm like bullying, harassment and unsafe working conditions may cause people to leave the workforce: on November 4 RNZ reported that Worksafe has reduced staff in its team monitoring and responding to psychosocial harm by 30%.

On November 4, the Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission released Urupare mōrearea: Crisis responses monitoring report. It found that crisis response services were fragmented, inconsistent and not working for Māori, young people or people living rurally: groups impacted by disproportionately high rates of unemployment and mental distress.

November 5 – unemployment data doubles down

Psychological distress, depression and anxiety can make it harder to enter or re-enter the workforce. Unemployment figures released on November 5 by Stats NZ showed that young people were disproportionately impacted by higher unemployment.

15.2% of young people aged 15-24 are out of work, compared to 13.1% a year earlier, and the overall unemployment rate of 5.3%.

The rate for 25-34 year-olds has also increased more than 1% in the year to September, up to 5.2%.

The NZHS shows that one in five (22.9%) 15-24 years-olds and 18% of 25-34 year-olds experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress, up from one in 20 (5.1% and 5.3% respectively) in each age band in 2011/12.

November 6 – the impact of long-term conditions

Long-term conditions also reduce a person’s ability to participate in paid employment. On November 6, University of Otago researchers spoke with Nine to Noon’s Kathryn Ryan on the experiences of long Covid patients and the toll the condition has taken on their physical health, mental health and employment prospects. On November 6, RNZ reported that mental health support service Lifeline was facing a $2 million shortfall, though it did not appear to be included in the minister’s $61.6 million crisis support announcement made on November 5.

Managed Decline found there has been a 33% increase in people leaving the workforce due to illness or injury between 2011 and 2024 (2.14% to 2.89%). For women, the increase was almost 50% (2.06% to 3.01%). Although the absolute numbers are small compared to the total labour force, the trend is concerning.

The determinants and drivers of health have a profound impact on our health and wellbeing, and if New Zealand continues on the current trajectory, the picture in 2035 is bleak: fewer than 7% of New Zealanders would describe their health as “excellent” .

The World Health Organisation has called on member states to recognise that health and the economy are interdependent, and good health for all is essential for the resilience and stability of economies globally. A healthy population is good for all of us – and it’s time for governments of all stripes to treat the health of the population as a long-term investment, rather than a short-term cost. This includes funding community-based services, such as Lifeline, Whakamātūtū and Rauaroha Segar House that have direct impacts on people’s health, wellbeing and connection with their communities.

The Ministry of Health will release the 2024/25 New Zealand Health Survey results this week: what will they reveal about the health of New Zealanders?

Harriet Wild is director of policy and research at ASMS, the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists.