To the best of our knowledge, there are limited publicly available studies conducted in this state with similar objectives. This study therefore contributes valuable insights to an under-researched area. Malaria vaccines are the end of the fight for total eradication of malaria in Africa and Nigeria in particular. Making the malaria vaccine widely accessible will be a significant accomplishment, but its degree of acceptance, particularly in developing nations, might provide another significant issue that must be addressed to ensure the program’s effective deployment. A study by Chukwuocha et al. [31], revealed that approximately half of the respondents were not aware of any prospective malaria vaccine. This is corroborated by the findings of this study, where more than half of the respondents were not aware of any effective malaria vaccine, especially the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine. Abdulkadir & Ajayi revealed a poor awareness level among caregivers of children-under-5-years [32]. This might be due to inadequate dissemination of information about the vaccine. Moreover, vaccination programmes have always had low awareness levels of COVID-19 [28] and the HPV vaccine [33]. The very few respondents who were aware of the vaccine noted that their source of information mostly came from healthcare providers and news media. This means that awareness of the malaria vaccine may take more than just formal education attainment; more graduates were represented in this study; and awareness is necessary to implement health interventions, such as malaria vaccine awareness. Two studies, one in Kenya [34] and the other in Ghana [2], revealed that consistent communication and health promotional activities and enlightenment from the populace on topical public health issues tend to play a major role in ensuring wide acceptance of any intervention. There is a need for consistent information, education, and communication on public health issues, especially for new and prospective interventions. Most importantly, the respondents affirmed that a malaria vaccine could be a very effective preventive tool against malaria. Informing pregnant women and nursing mothers about the malaria vaccine would likely increase their interest in their willingness to allow their children to be vaccinated. Thus, creating awareness of the malaria vaccine could reveal policy-related issues that, if addressed, could facilitate the delivery of this intervention and child vaccinations [35].

Furthermore, acceptance of this R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine and willingness to allow their children to be vaccinated against malaria if the vaccine is made available stemmed from several positive results recorded from previous vaccination programme [2]. This study revealed a high percentage of willingness to use the vaccine, as reported by high agreement among pregnant women and nursing mothers regarding the addition of the vaccine to the normal immunization regimen for all children. This finding is consistent with several studies that reported a strong understanding of the benefits of the malaria vaccine to child vaccinations [2, 34,35,36].

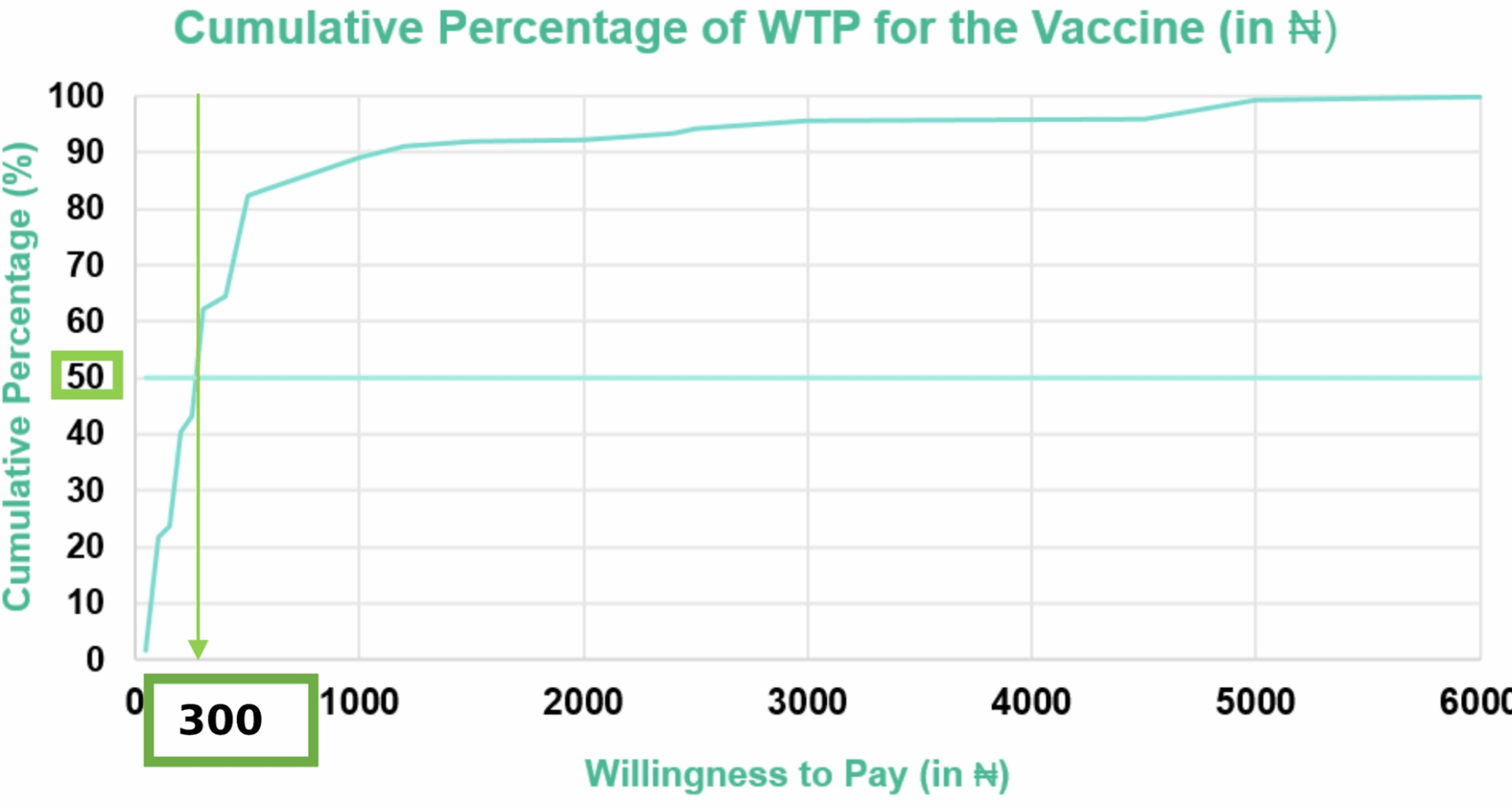

Quite encouraging, most of the respondents reported their WTP for their child to be vaccinated. This is similar to other WTP studies conducted elsewhere; in Ecuador, 85% of the respondents were willing to pay for a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine. The median WTP value of the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine as declared in this study was USD 0.38 (₦300.00). This implies that 50% of the respondents stated that they would accept a maximum payment of USD 0.38 (₦300.00) or less. The median value is usually used in declaring the WTP value to minimize the extreme values (outliers). A lower WTP value of USD 6.77, USD 6.70 and USD 5.06 was reported for hypothetical malaria vaccines in Nigeria, with varying efficacies of 75%, 85%, and 95%, respectively [24]. When adjusted for inflation, these WTP values are still comparable. While most childhood vaccines are free in Nigeria, WTP studies are always geared toward ascertaining the value the recipients are willing to pay for the vaccine if it is not free, as such cost and affordability have been associated with hesitancy and noncompliance with some health interventions, especially in low-middle-income countries, and can hamper the success of such interventions, such as malaria.

Finally, age, occupation, and health insurance were factors that were significantly associated with the WTP of the respondents. A study by Lu et al. identified age as a factor significantly associated with WTP for the HPV vaccine, where older people are more willing to pay than other age groups are [37]. This study revealed that respondents aged 18–21 years are more willing to pay. Unexpectedly, family income was not a significant predictor of higher WTP, as commonly reported in several WTP studies [22, 24]. Hence, it is critical to roll out a hybrid payment system such that the vaccine is made free of charge for low-income groups, whereas high-income groups pay for the vaccine.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, as a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study, the responses may not fully reflect participants’ actual behaviours or attitudes, since variables were measured at a single point in time. Future studies should therefore collect data at multiple time points to capture changes in awareness, acceptability, and WTP, thereby providing a stronger basis for decision-making on malaria vaccine promotion, communication, and resource allocation. Second, the study is subject to cognitive and response bias, as participants were aware of the study’s purpose, and no blinding or control for confounders was applied, which may affect the validity of the findings. Third, the study was conducted only in Nsukka and one location in Enugu city, which limits its generalizability to all nursing mothers in Enugu State or Nigeria, even though Enugu city is a metropolis with a diverse population. Lastly, because the vaccine is generally considered a necessity that should be provided at no cost, the WTP values reported may have been underestimated, despite respondents being informed of the study’s intention during data collection.

Recommendations

To increase awareness, acceptability, and willingness to pay for the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine, a comprehensive strategy involving the government, society, and nursing mothers is essential. First, government is encouraged to allocate funds to subsidize the vaccine’s cost, making it more accessible to all socioeconomic groups. Investing in public health campaigns can increase awareness of the importance of vaccines, and integrating vaccination into existing healthcare policies ensures widespread coverage. Additionally, collaboration with international health organizations is crucial for a well-rounded approach. Society plays a pivotal role in vaccine adoption. Community engagement is vital; involving local leaders and healthcare workers can address cultural beliefs and misconceptions. Tailoring vaccination campaigns to respect cultural norms and practices and promoting health literacy can break down barriers. By incorporating local languages and adjusting vaccination schedules, cultural sensitivity is ensured. Within communities, pregnant women and nursing mothers should have easy access to healthcare facilities, especially in remote areas. Education and counseling should be offered, addressing concerns related to vaccine safety, efficacy, and side effects. Advocacy for policies that reduce financial burdens on nursing mothers, such as free or low-cost vaccinations, is essential. Leveraging local celebrities and influencers such as ‘Vaccine_pharmacist’ can amplify vaccination campaigns.