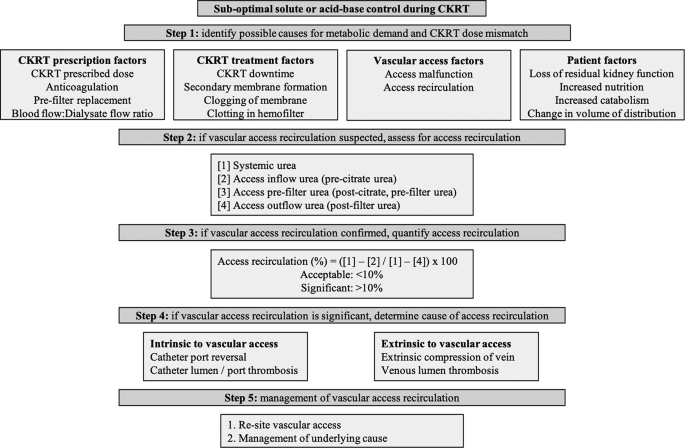

We have reported a case with sub-optimal solute and acid base control despite adequate prescribed dose of CKRT-RCA delivered uninterrupted. Systematic assessment of factors identified AR as the cause of compromised CKRT dose delivery. Our case presented us several learning points which are discussed below, along with a proposed systematic approach to evaluate inadequate CKRT dose delivery and AR (Fig. 4).

Algorithm for evaluation and management of vascular access recirculation in continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT)

Post-operative AKI may be seen in up to 13.4% of patients subjected to non-cardiac surgery [3]. In patients with AKI who develop complications such as hyperkalaemia, metabolic acidosis or fluid overload refractory to medical management, initiation of dialysis is indicated [4, 5]. To allow uninterrupted delivery of appropriate dialysis dose, and in absence of contraindications, RCA is the preferred anticoagulation choice for CKRT [6].

When CKRT efficacy is suboptimal, we need to assess patient and treatment factors. Patient factors include increased catabolism, higher nutritional supplementation, altered volume of distribution, and worsening renal function. Treatment factors include prescription issues (no anticoagulation, high filtration fraction, pre-dilution replacement), delivery issues (interruptions from procedures, alarms, bag changes), technical issues (secondary membrane formation, membrane clogging), and vascular access problems [7, 8].

The key to successful delivery of dialysis remains an optimally functioning vascular access. Temporary NTDC are most common vascular access for CKRT. In patients where dialysis may be required for beyond 2–3 weeks, a cuffed tunnelled dialysis catheter should be considered [9]. Vascular access recirculation, an under-recognized complication of dialysis catheter, occurs when dialyzed blood exiting from the outflow line, instead of returning to systemic circulation, re-enters the inflow line and recirculates through the dialyzer. The severity of recirculation determines the magnitude of dilution of un-dialyzed blood from the systemic circulation flowing into the in-flow line of the circuit [10]. In dual-lumen dialysis catheters, the incidence of AR ranges from 2 to 15% [2]. The main causes of AR are thrombosis, both intrinsic and extrinsic to vascular access, as well as inappropriate catheter length, catheter tip position, intravascular volume status, catheter ports abutting vessel wall, and extrinsic compression [11]. Intrinsic thrombi, found in up to 18% of catheters are formed within the lumen (intraluminal), at the tip or within the sleeve surrounding the catheter (fibrin sheath), whereas extrinsic thrombi form outside but can sometimes be attached to the catheter [12]. All the above factors are modifiable and ought to be considered during assessment for reduced efficacy of CKRT. Very often, the management involves removal and re-siting an appropriate dialysis catheter.

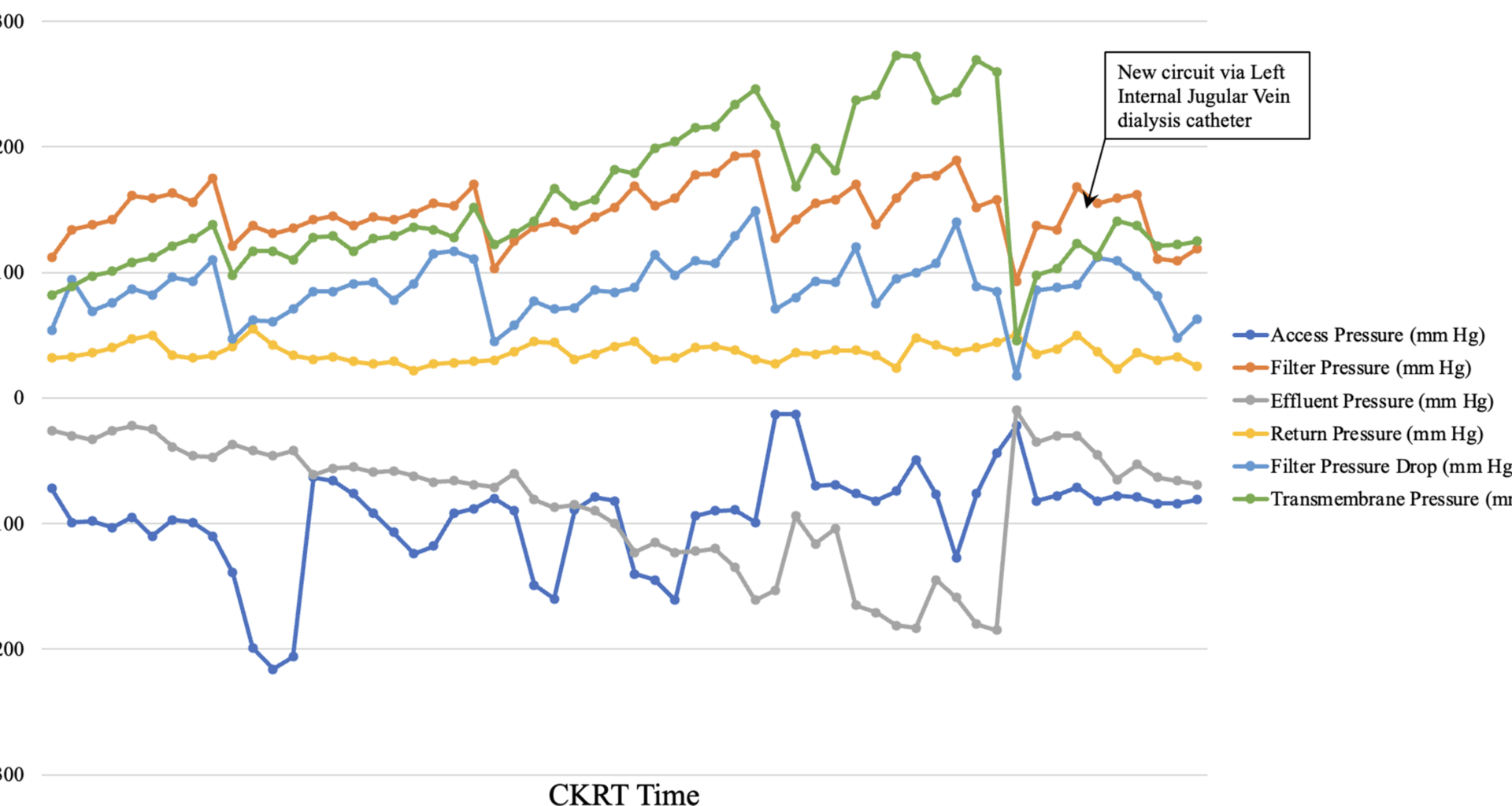

The persistent but stable metabolic abnormalities in our patient may be explained by significant AR secondary to development of a new clot in the infra-renal IVC just distal to the tip of the right femoral NTDC. Though CT venogram showed a partially occlusive IVC thrombus causing marked recirculation (> 90%), some perithrombus flow likely persisted, permitting limited solute clearance. Effectively, a “very low dose of CKRT” was being delivered to the patient, partially meeting the ongoing metabolic demands, but not adequately correcting the metabolic abnormalities. In fact, this may also have been responsible for the slight delay in the diagnosis of AR in our case.

Cancer confers a four-fold increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and 1 in 20 cancer patients will develop VTE in the course of their disease [13]. Indwelling catheters and blood transfusions have been identified as some treatment-related risk factors for VTE in patients with cancer [14]. The patient discussed above developed extensive venous thrombosis in the right internal jugular, subclavian and brachiocephalic vein and subsequently in the IVC.

Once suspected, AR must be quantified by any one of the various urea or non-urea-based methods [10, 15,16,17]. Measuring blood urea levels from systemic circulation, access line and return line sampling ports provides a quick and easy measure of AR: AR = [Systemic Urea – Access urea] / [Systemic Urea – Post-filter Urea] [15]. In our patient using described urea-based method we quantified AR to be > 90%.

Many current CKRT-RCA protocols allow infusion of IV calcium into the venous return line of the CKRT circuit. In our institution, we administer IV calcium separately into a central venous line via an infusion pump. This explained the finding of extremely low total and ionized calcium levels from access line and post-filter sampling ports, as significant AR caused local accumulation of citrate but not calcium. If IV calcium was administered in the venous return line of CKRT circuit, there would have been concomitant local calcium accumulation, leading to a post-filter ionized calcium closer to the expected range of 0.25–0.40 mmol/L. Therefore, our practice allowed us to also demonstrate AR by measuring the pre- and post-filter total and ionized calcium levels. Alternatively, it may be argued, regular 6 hourly monitoring of post-filter ionized calcium may have highlighted the recirculation issues earlier. Our protocol has abandoned the regular monitoring of post-filter ionized calcium as the current analyzers may not be calibrated to measure extremely low levels of ionic calcium and may result in multiple, but unnecessary, adjustments in citrate dose [18].

In the context of RCA, the development of, or persistence of elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis suggests two possible differential diagnosis: inadequate citrate/ buffer delivery or citrate accumulation [19]. The former is usually suspected when the patient is relatively stable or improving, metabolic acidosis is persistent but stable, there is no progressive decrease in systemic ionized calcium level requiring increasing IV calcium replacement, and therefore the ratio of systemic total to ionized calcium is < 2.5. On the other hand, citrate accumulation is diagnosed by demonstrating a triad of progressively worsening elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis, low systemic ionized calcium level requiring increasing IV calcium replacement, and consequently a systemic total to ionized calcium ratio of > 2.5. Citrate accumulation should be suspected in patients whose clinical or haemodynamic condition is worsening progressively, along with rising serum lactate. In the case discussed, after initiation of CKRT-RCA there was expected improvement in solute and acid base parameters. However, beyond 12 h, the patient’s metabolic abnormalities persisted but remained stable, with normal serum lactate and ketones and absence of worsening haemodynamic status. The post-filter ionized calcium of 0.23 mmol/L suggested an adequately anticoagulated circuit. Due to calcium load from IV calcium, her systemic total and ionized calcium levels increased, leading to periods when IV calcium replacement was reduced to 0 mL/hour. To increase buffer supply, her dialysate flow rate was increased from 800 mL/hour to 1200 mL/hour, without any significant impact.

A review of literature identified 3 reports of severe AR in CKRT-RCA leading to sub-optimal CKRT delivery. The first report was of a child post-cardiac surgery, where AR secondary to CathPR, resulted in a significantly low systemic ionized calcium when measured from vascular access sampling port. A simultaneous systemic ionized calcium from patient’s radial artery catheter revealed asymptomatic hypercalcemia [20]. Second report was in an adult patient where deep iliac vein thrombosis caused 96% AR by Day 12 of CKRT and led to low calcium levels in the circuit but high calcium levels in the patient due to excessive calcium load provided by IV calcium [21]. In response to this finding there was progressive decrease in citrate and IV calcium flow up to zero in their patient. Access recirculation was suspected due to increase in return CKRT pressure and multiple episodes of filter clotting. The most recent report highlighted 3 patients with COVID-19, who developed AR due to thrombus and calcification at tip of catheter between 7 and 53 days after commencing CKRT-RCA [22]. All patients were using a left sided femoral non-tunnelled dialysis catheter. All patients were diagnosed with AR as: (1) they displayed very low circuit urea levels and post-filter ionized calcium levels due to local citrate overload; and (2) systemic total and ionized calcium increased due to IV calcium replacement but total to ionized calcium ratio remained < 2.5. In contrast, AR was suspected in our patient due to suboptimal solute and acid-base control, along with a progressive increase in both systemic total and ionized calcium levels despite reduction of calcium replacement, and a total to ionized calcium ratio remaining below 2.5.