Scientists have identified a new species of non-biting midge from 151-million-year-old specimens discovered by an amateur fossil hunter. Credit: Louise Reily / Australian Museum

Scientists have identified a new species of non-biting midge from 151-million-year-old specimens discovered by an amateur fossil hunter. Credit: Louise Reily / Australian Museum

An 82-year-old man from Australia with a lifelong passion for fossils but no formal training in paleontology has helped scientists challenge a long-standing idea about how a tiny but widespread group of insects first evolved.

His fossils, collected over a decade at a Jurassic site in New South Wales, have revealed a new species of non-biting midge. Although about the size of a grain of rice, this tiny ancient insect can reveal much about prehistoric Earth and may prompt scientists to rethink where these freshwater insects first emerged.

Researchers named it Telmatomyia talbragarica, meaning a “fly from the stagnant waters.” The new study, published in the journal Gondwana Research, identifies the oldest non-biting midge ever found in the Southern Hemisphere.

A Fossil Hunter’s Dream Come True

Beattie’s career was in classrooms, where he taught science and agriculture. Fossils were more like a hobby. “I couldn’t believe it,” he once said of his childhood find, according to The Guardian. “I’ve been interested in fossils ever since.”

He brought specimen after specimen to the Australian Museum. Things like fish pulled from an old sewer tunnel or beetles from abandoned quarries. And, eventually, a handful of delicate insects from the Talbragar Fish Beds, an ancient lake deposit ringed by volcanic ash and Jurassic conifers.

“We really didn’t understand the importance until we started studying them quite recently,” Matthew McCurry of the Australian Museum also told The Guardian. Their significance only became clear after years of detailed microscopy, phylogenetic analysis, and comparison with other fossils.

The fossils turned out to be about 151 million years old. They belonged to a group of non-biting midges called Podonominae, insects that today help anchor freshwater ecosystems and are especially abundant in the Southern Hemisphere.

Southern Origins

Scientists believed these midges originated in the North. The oldest known fossils came from Siberia and China, and the prevailing idea was that the insects evolved on Laurasia, the northern supercontinent, before spreading south.

But the Talbragar specimens flipped the pattern.

“This fossil, which is the oldest registered find in the Southern Hemisphere, indicates that this group of freshwater animals might have originated on the southern supercontinent of Gondwana,” said Viktor Baranov of the Doñana Biological Station, first author of the study.

The finding suggests the insects may have first evolved in the Southern Hemisphere, which fits with their strong presence today in places like Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Around 80% of insect species occur in the Southern Hemisphere.

A Strange Adaptation

T. talbragarica also possesses an unexpected trait, one previously known only in marine midges.

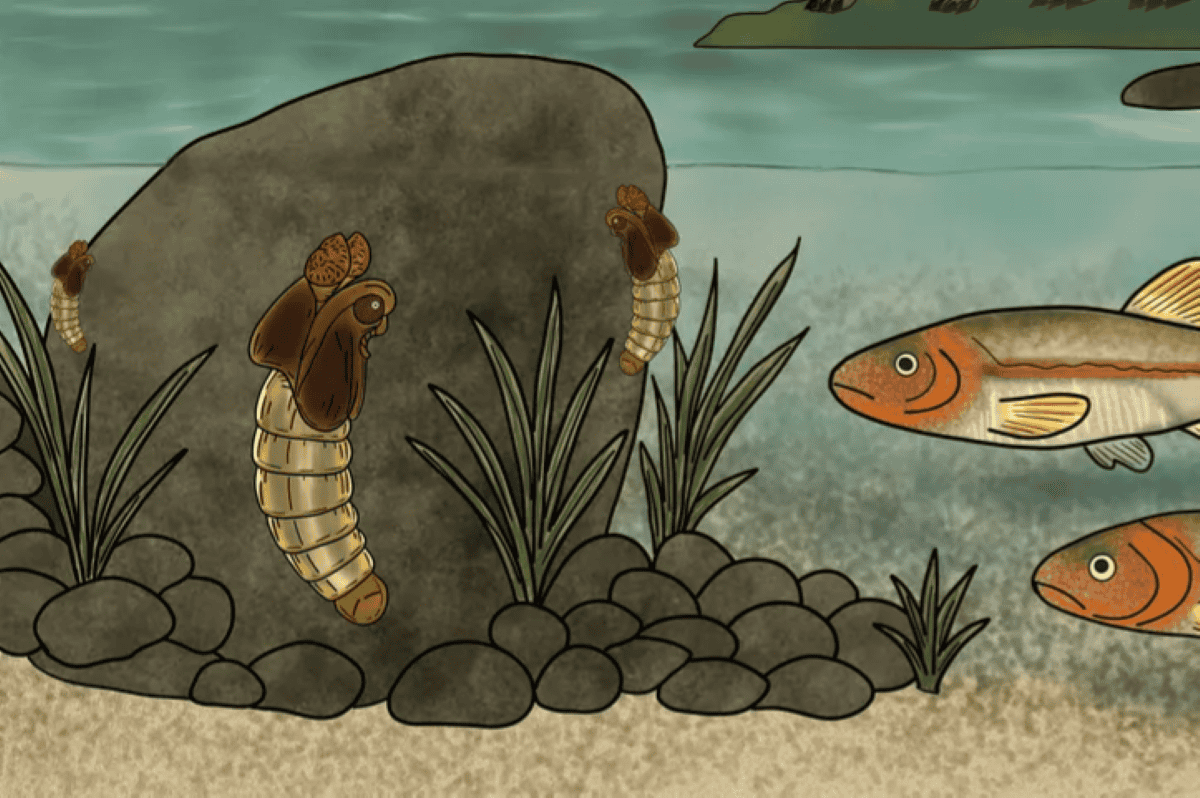

The pupae carry a suction disc at the tip of the abdomen. The structure allowed the young insects to cling to submerged rocks in rough water. Until now, scientists believed such adaptations evolved only in species living in tidal zones.

Finding them in a freshwater lake was a surprise.

Artist’s rendition of the prehistoric freshwater midge. Credit: Valentyna Inshyna

Artist’s rendition of the prehistoric freshwater midge. Credit: Valentyna Inshyna

The Talbragar lake once teemed with fish, dragonflies, and towering conifers. The midge pupae lived along its shallow edges, attached firmly to stones in choppy currents.

“This midge in particular … is an example of the fact that when we actually do look in the southern hemisphere, there are fossils to find, and they can start to correct that understanding,” McCurry added.

Why This Midge Matters

At first glance, the new species seems insignificant. It lived briefly in a pond overshadowed by dinosaurs. Yet here we are, millions of years later, with evidence of its existence.

The truth is that freshwater ecosystems rely on midges. They help cycle nutrients and support fish. Their modern descendants span continents. Understanding where they came from helps explain how biodiversity spreads, shifts, and endures.

The study also highlights how important amateur fossil hunters can be. And Beattie isn’t finished yet. He continues to explore, collect, and share. When asked how it feels to make a discovery that reshapes evolutionary thought, he simply shrugged. “Oh, we all do it,” he told The Guardian. “Lots of people find all sorts.”