Fascia: It’s neither muscle, bone, tendon, nor ligament, but it’s crucial to how bodies move. So what is it, what does it do, and how can dancers keep theirs healthy?

Pointe spoke with physical therapist Dr. Jessi White, owner and founder of Statera Wellness, to find the answers to these questions. Read on for an overview of fascia for dancers.

What Is Fascia?

According to White, fascia is a connective tissue that runs all throughout the body, holding our muscles, organs, bones, tendons, and even nerves in place. Composed of collagen, elastin, and ground substance (a gel-like substance in most of the body’s connective tissues), it provides both structure and flexibility, which helps our bodies move. There are different kinds of fascia, says White, but for dancers, it’s most helpful to think about its relationship to muscles.

How Does Fascia Work?

![]() Dr. Jessi White. Photo by Aria Smith of Planes and Pixels, courtesy White.

Dr. Jessi White. Photo by Aria Smith of Planes and Pixels, courtesy White.

Fascia helps define muscle groups. White uses a burrito analogy to provide a visual, with muscles as the filling and fascia as the tortilla. “Muscles can contract and move by themselves,” she says, “but wrapped in fascia, they become much more efficient.” She adds that fascia has three key functional characteristics: tensegrity, thixotropy, and myofascial structure:

Tensegrity is the ability to combine tension and compression, which creates stability in muscles and joints.

Thixotropy is a substance’s ability to move between more solid and fluid states. “Fascia can become softer and more elastic, which allows our body to stretch and bend,” says White.

Fascia’s myofascial structure involves its interconnectedness with muscle. When a muscle contracts, it pushes against the fascia, creating resistance and generating more force, says White. “Fascia allows us to be stronger, create more power, and jump higher.”

What Is Fascial Injury?

Because fascia is intertwined with the body’s various tissues, fascial injury can be difficult to define, says White. “Oftentimes when we see fascia that’s not working well, it’s because there’s been a traumatic injury, like a torn muscle or tendon. The fascia in that area probably also tore.”

If the connective tissue between fascia and muscle grows too rigid, the fascia can also become “stuck down,” continues White. This is also known as “adhesion” (think: scar tissue), and it affects muscles’ ability to contract and move correctly. This can contribute to feelings of weakness, tightness, or delayed recovery from overuse issues, like tendonitis.

With either traumatic or chronic injury, it’s crucial to consider the full picture: “If we don’t step back and look at how fascia connects to the entire body, we may miss a part of the healing process.”

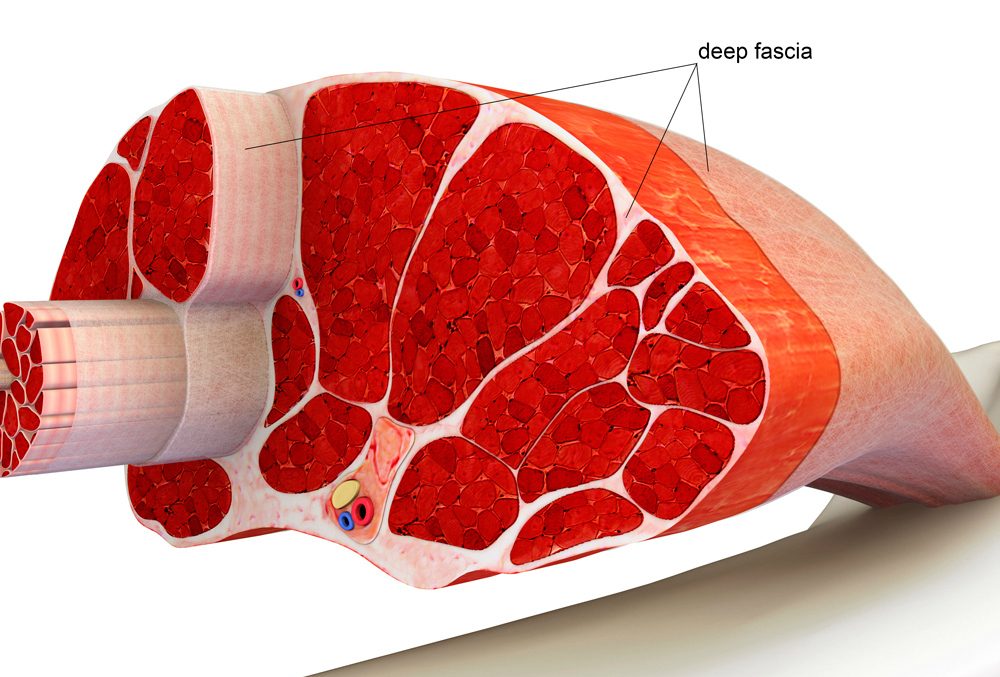

A rendering of deep fascia. Photo courtesy White.

A rendering of deep fascia. Photo courtesy White.

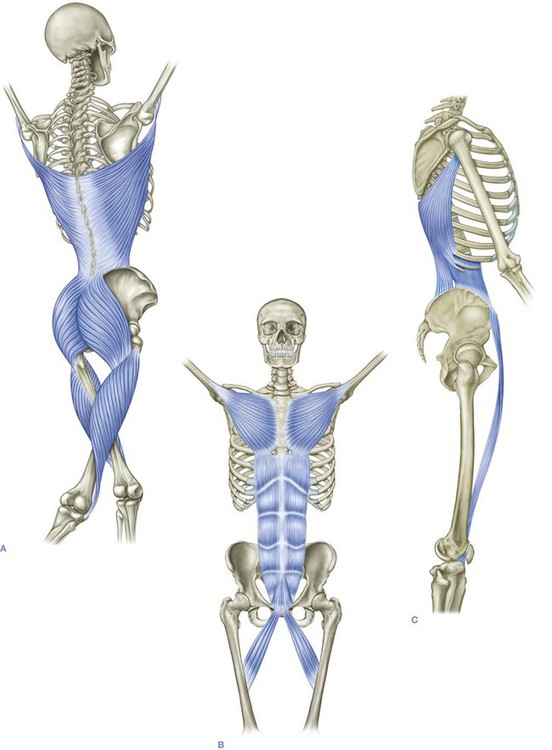

What Are Fascial Slings?

A full-picture view is also important because of systems known as fascial slings, which connect muscle groups across the body. The posterior oblique sling, for example, connects the shoulder to the opposite hip, across the back. White explains that if a dancer’s left arabesque isn’t as high as the right, they could try doing some stability exercises for the right shoulder blade outside of class. “There may be a disconnect where the fascia isn’t working as well across that [sling] line.”

Sometimes, she says, when dancers have a knot, the myofascial connection can send the pain signal to a different part of the body. This can make it difficult for dancers to self-treat trigger points through self-massage, foam rolling, or other at-home release methods. White, who is certified in myofascial trigger-point therapy and dry needling, recommends triggerpoints.net for a visual of trigger-point pain-referral areas connected by fascia. If self-treatment isn’t working, dancers should consult a physical therapist or an athletic trainer.

How to Treat Fascial Injury

Fascial lines. Photo courtesy White/Basicmedical Key.

Fascial lines. Photo courtesy White/Basicmedical Key.

When it comes to fascia, different kinds of massage target different issues. White explains that with trigger-point or deep-tissue massage, the fascia ideally gives and allows pressure to transfer to the knot deep inside the muscle. But if the fascia is too rigid, prolonged or increased pressure can cause it to stiffen further. In those cases, “a lighter type of massage, called myofascial release, is better,” she says. “We gently pull at the fibers to get them to stretch and separate.”

Another option is dry needling, which targets knots and disrupts the bond between the fascia and muscle. “If you’ve ever seen a piece of raw meat, that shiny outer layer is fascia,” says White. “When you peel it off, you’ll notice the cobweb-like structure that has to separate. That’s the bond with the muscle.” If that bond is too rigid and is causing myofascial pain, dry needling can provide immediate relief. Since dancers are generally bendy people, White assigns them exercises to create healthy stability after releasing the tissue: “What’s good for our whole body is also good for our fascia.”

How to Keep Fascia Healthy

White says that fascia requires hydration and movement to remain pliable. Dancers should drink plenty of water and do non-ballet movement on days off to keep fascia supple. (She suggests yoga, hiking, or swimming, though any non-ballet exercise will do.) Massage and foam-rolling also help, but don’t try rolling out your IT band, she warns. “It’s a really thick, different kind of fascia that doesn’t stretch.” Instead, target major muscle groups, like the quads.

Dancers should also warm up properly before each class and rehearsal, elevating their heart rates to increase blood flow to muscles and fascia. Heating pads can provide relief, White says, but don’t use them for too long (maximum 15 to 20 minutes at a time, to avoid burns). “Do all things in moderation.”