The Vallarta mud turtle, the world’s smallest turtle, lives only in temporary lagoons in the Mexican city of Puerto Vallarta, which poses a huge challenge for its conservation.By the time scientists had determined they were a distinct species, just 1,000 turtles remained; since then, their number has dropped to 300.A key driver of this decline is the illegal pet trade, with an estimated 200 turtles smuggled to China this year alone, according to experts.Even though the turtle is listed as critically endangered, Mexican authorities have been slow to implement measures to protect it or its habitat, which is being lost to tourism developments.

See All Key Ideas

It sounds like a scene out of the Ocean’s series of heist movies. Only this one didn’t happen in Las Vegas, but at a Mexican university campus surrounded by lush tropical vegetation. And it wasn’t about taking on a casino, but stealing valuable turtles. Armando Escobedo Galván, a biologist at Centro Universitario de la Costa (CUC) in Puerto Vallarta, on Mexico’s Pacific Coast, says he’s still startled about how the thieves tricked him last December.

“Two people arrived at my office,” he recounts, “wearing uniforms of the environmental prosecutor’s office,” a federal agency known as PROFEPA. They said they were there for an inspection of his turtle program, asked for his permits, and cited corresponding laws. Everything during the two-hour procedure seemed completely normal. Then they asked to see the laboratory where the turtles were kept for scientific research: a climate-controlled container, secured with a padlock.

That’s when the problems began. The officials criticized the way the turtles were being kept and complained about missing permits. Escobedo Galván says he started feeling stressed. They threatened to punish him, he says, so he was relieved when they offered instead to take 40 of the 100 turtles into their “protection” while he sorted out the necessary paperwork.

“We’ll bring them back when everything is in order,” Escobedo Galván recalls them telling him.

“That was a psychological masterpiece,” he says. “They put me under pressure and then offered a solution.”

Measuring only 10 centimeters (4 inches) in length, the Vallarta mud turtle is the smallest turtle in the world. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

Measuring only 10 centimeters (4 inches) in length, the Vallarta mud turtle is the smallest turtle in the world. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

So he handed the turtles over.

It was only two weeks later, during a conversation with regional representatives of PROFEPA, that the professor learned they had never ordered such an inspection. A few days later, friends sent him photos of his turtles, now being offered for sale on Facebook in Hong Kong for tens of thousands of dollars each.

“We recognized some because we had marked them on their shells,“ Escobedo Galván says.

He filed a complaint, and federal prosecutors arrived at the university campus with local reporters in tow. It was newsworthy because the stolen turtles were a rare species: casquito de Vallarta, or the Vallarta mud turtle (Kinosternon vogti), the smallest turtle in the world, found only in Bahia Banderas, a bay between Puerto Vallarta and Nuevo Nayarit.

The turtles around the corner

It’s unclear how long the Vallarta mud turtle has been living in the region. The first scientific study about the species was published in 2018, with Escobedo Galván, a herpetologist, one of the co-authors. He had come to Puerto Vallarta at the invitation of fellow professor Fabio Cupul Magaña.

“A few days after my arrival, he took a jar out of the cupboard containing a tiny turtle preserved in alcohol with a yellow spot on its nose, and said that it had been in the university a long time and asked if I could identify the species,” Escobedo Galván tells Mongabay.

A search began, involving other turtle experts from different universities. At first, they thought it was a genetic mutation of the Jalisco mud turtle (Kinosternon chimalhuaca), which lives a little farther south. Then, they found some of the same turtles just around the corner, in some of the wetlands near the university campus. Locals recognized the turtles as ones they’d spotted since their childhood.

For the scientific community and turtle enthusiasts worldwide, it was a pleasant surprise when the new species was announced. Mexican scientists named it in honor of U.S. herpetologist Richard Carl “Dick” Vogt, who had worked for several years in Mexico and made many contributions to herpetology, including the important finding that the sex of turtle offspring is linked to egg incubation temperature, and that turtles use vocalizations to communicate to one another.

But the good news was tempered by the fact that the recently discovered turtle’s habitat was rapidly shrinking.

Sebastián Flores from Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza measures a Vallarta mud turtle. The turtle was handed in by people who found it on the street; it will be released back into its habitat. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

Sebastián Flores from Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza measures a Vallarta mud turtle. The turtle was handed in by people who found it on the street; it will be released back into its habitat. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

“We counted back then only thousand of those turtles in temporary lagoons in Puerto Vallarta,” says Alejandra Monsiváis Molina, director of Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza (Students Conserving Nature), a local environmental group. The NGO is partially financed by the Turtle Survival Alliance, a global conservation organization dedicated to preventing the extinction of tortoise and freshwater turtle species through coordinated conservation programs, including in-situ protection, captive breeding and species monitoring.

As the TSA’s local partner in Puerto Vallarta, Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza monitors turtles, organizes workshops and works to get the government and the private sector on board with conservation. Together with scientists, it pushed for the newly described turtle to be listed by the IUCN, the global wildlife conservation authority, as a critically endangered species.

A habitat on private property

Monsiváis Molina says she’d hoped that achieving this status would shake up the government and prompt it to take swift protective measures. But nothing happened. Since then, their numbers have dwindled, Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza tells Mongabay. Torsten Blanck from the Austrian branch of the U.S. NGO Turtle Island, who is also trying to help the Vallarta mud turtle, estimates that there are no more than 300 individuals left in the wild and that their habitat has shrunk to barely 20 hectares (50 acres) across four lagoons, down from eight when they were discovered. That’s because the mud turtle’s habitat is being swallowed up by a rapidly growing city. Puerto Vallarta, a popular vacation destination for Hollywood stars since the 1960s, still attracts retirees from the U.S. and Canada. Every year, the city is losing dozens of hectares of land to the construction of roads, golf courses, hotels, supermarkets and apartment blocks.

This poses a huge threat for the turtles, which, during the rainy season from May to September, live in the shallow waters of the temporary lagoons that pop up in the swamps of Bahia Banderas. With the onset of the dry season, they bury themselves deep in the ground.

Over the last two years, however, two of these lagoons have been lost to real estate developments, without any intervention from local authorities or the environment ministry, known by the acronym SEMARNAT, which is legally obligated to check the environmental impact studies and could stop harmful projects or force modifications and impose fines for violations. Mongabay contacted various officials at SEMARNAT for comment, but didn’t receive an answer.

The environment hasn’t been a priority for Mexico’s last two leftist governments, which have slashed funding for environmental programs over the last seven years. That includes the current administration under President Claudia Sheinbaum, a former member of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, who oversaw a 36% cut in funding in the 2025 budget. Many government staffers working on environmental issues have been laid off, and the pressure on those remaining is piling up as Sheinbaum seeks to revive the sluggish economy.

Given the uncertainties on the trade front due to the tariffs imposed by the U.S. government, Mexico is betting big on tourism — and Puerto Vallarta remains an attractive destination and paradise for real estate investors.

Environmentalists briefly considered buying one of the turtle habitats that lies within private property, but the landowner asked for 9 million pesos ($492,000) for the 1-hectare (2.5-acre) area. “That’s impossible, even if we all pool our money in,” Blanck says.

Puerto Vallarta municipal officials started to build a wall around one of the lagoons to prevent intrusion. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

Puerto Vallarta municipal officials started to build a wall around one of the lagoons to prevent intrusion. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

Over the last year, construction of some developments in the area has begun, according to Monsiváis Molina and Blanck. Other developers, such as Grupo Vidanta, which operates a golf resort near the Puerto Vallarta airport, have denied turtle experts access to their land. Residents have spotted mud turtles on the surrounding roads. Some miles farther, another landowner burned down bushes and sent in excavators last year, without prior information, according to Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza.

Authorities remain silent

When the environmentalists arrived, hundreds of turtles had been burned or flattened, among them dozens of Vallarta mud turtles. Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza informed authorities and filed a report to SEMARNAT in January.

Ten months later, “we are still waiting for a response,” Monsivais Molina says.

The silence from the authorities is incomprehensible for them: Mexico’s environment minister, Alicia Bárcena, is a biologist and, as former executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL), was a driving force behind the drafting of the Escazú Environmental Agreement. That regional treaty, which Mexico ratified in 2020, includes provisions to protect environmental human rights defenders and guarantees public participation in environmental decision-making and access to relevant information.

But so far, authorities have shown little interest in the fate of the Vallarta mud turtle. Last December, federal, regional and municipal authorities inaugurated a bypass road to address the chronic traffic jams around the Puerto Vallarta airport. It cut in half one of the biggest, most populated and best-preserved turtle habitats, sacrificing an entire lagoon for the construction. Mongabay has asked the authorities for access to the environmental impact study, but hasn’t received a response yet.

Things will change from now on, says Vincent O‘Halloran Lepe, Puerto Vallarta’s municipal secretary of sustainability and urban planning. He welcomes Mongabay at his air-conditioned office, with a Vallarta mud turtle stuffed toy sitting next to the computer on his desk. A trained biologist, he started his job in October 2024, together with the new mayor from the Green Party.

The party’s historical role has been as a junior coalition partner for the major parties, and today is part of the coalition led by Sheinbaum’s left-wing nationalist Morena Party.

“The problem with this turtle is that it is living in the middle of the city,” O’Halloran Lepe says. Another problem, he says, is that it’s small habitat is split between two states, Jalisco and Nayarit, which are governed by different parties.

The team of Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza has found more than 30 traps set by smugglers this year; authorities confiscated three more. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

The team of Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza has found more than 30 traps set by smugglers this year; authorities confiscated three more. Image by Sandra Weiss for Mongabay.

O’Halloran Lepe says he’s figured out a partial solution. Two of the turtle lagoons are public land under the municipal administration. One, the Cuapinole lagoon, in the northern part of Puerto Vallarta, is surrounded by streets and homes that have for decades dumped their waste into the lagoon. Several years ago, the municipality cleaned up the lagoon and fenced it off.

But then, according to O’Halloran Lepe and Monsiváis Molina, someone released a red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) into the water, probably a pet they wanted to get rid of. Since then, this invasive species, native to northern Mexico, has proliferated and, in some cases, cross-bred with the mud turtle. Environmentalists warned that unless the invasive species was eradicated, this lagoon could no longer serve as Vallarta mud turtle habitat.

The second lagoon, Tomasa, isn’t only located on public — it’s also designated as a natural biotope, O’Halloran Lepe says. However, even this low-level protection status hasn’t been enforced, and the lagoon was also used by construction companies to dump their rubble.

Thanks to a donation campaign organized by Estudiantes Conservando la Naturaleza, the municipality cleaned up the waste and is now building a wall around the lagoon. Trained neighbors are helping to monitor the turtles there and reporting on intruders and illegal turtle traps set by smugglers. Until recently, they removed the traps themselves, but stopped after receiving threats.

That’s why the city is planning to install permanent surveillance camps in three lagoons during the rainy season, according to O’Halloran Lepe.

“There will be municipal police and students to deter poachers,“ he says.

Three weeks after Mongabay’s visit, however, when we reach out to O’Halloran Lepe for an update, he admits they haven’t managed to achieve that, saying they were kept busy preparing the mayor’s annual report. In the medium term, he says, the plan is to convert the lagoon into an eco-park: a protected area that includes a site for captive breeding and scientific work, which will also benefit local residents with jobs as tour and nature guides.

“We think of this lagoon as the main refuge for the species,“ O’Halloran Lepe says.

He declines to talk about the possibility of expropriating the remaining private lagoons, saying the local government is working with other authorities about a coherent and binding conservation strategy.

Smugglers sense an opportunity

Smugglers have been quick to take advantage of authorities’ delayed response. The media coverage of the theft at Escobedo Galván’s lab alerted international smuggling networks to the opportunity to be had here.

“At the beginning of the year, we started to hear about people offering as much as 20,000 pesos [$1,100] per turtle to locals,“ Escobedo Galván says.

Mexican officials seize a load of smuggled turtles at the Mexico City airport, among them Vallarta mud turtles. Image courtesy of PROFEPA.

Mexican officials seize a load of smuggled turtles at the Mexico City airport, among them Vallarta mud turtles. Image courtesy of PROFEPA.

That’s usually how wildlife trafficking works in Mexico: the risky jobs such as stealing, hiding and transporting the animals is outsourced to locals. By the time it reaches the black market in Asia, a Vallarta mud turtle can sell for $10,000 or more.

The university reinforced security measures; it put up a fence around the turtle lab container and installed cameras. Yet even that wasn’t enough. In January this year, a month after the first heist, thieves broke through the university’s perimeter fence, broke the locks of the container, and took another 15 turtles. The surveillance cameras showed they were young men wearing hoodies, who were in and out in just three minutes. This time, the story reached the national media.

“I then felt that authorities started to shift their attitudes, paying more attention to the turtles,” Escobedo Galván says.

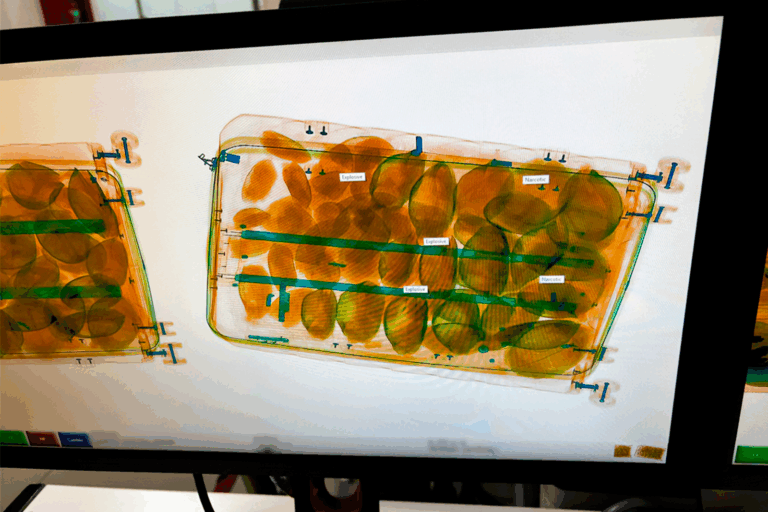

The smuggled turtles were hidden in small packages in baggage, but were clearly visible on the X-ray machine. Image courtesy of PROFEPA.

The smuggled turtles were hidden in small packages in baggage, but were clearly visible on the X-ray machine. Image courtesy of PROFEPA.

In February, authorities at the Mexico City airport confiscated two bags destined for Japan with a large number of smuggled turtles inside them, among them several Vallarta mud turtles. Authorities arrested one person and launched an investigation. In May, also in Mexico City, they arrested one of the fake inspectors who had conned Escobedo Galván the first time around. In September, police and soldiers raided three farms in two different Mexican states and found a dozen protected species, among them 12 mud turtles. They arrested three men suspected of working for the smuggling network, and charged them under organized crime statues.

PROFEPA, the environmental prosecutors’ office, told Mongabay that throughout 2025, they’ve confiscated 121 Vallarta mud turtles, destroyed three traps, and organized three night raids together with security forces.

No action could bring the demise of the species

Environmentalists have welcomed these actions, but say they’re insufficient, given the urgency and the high price collectors pay. Blanck estimates that at least 200 mud turtles have been smuggled to China in the past year alone.

“At this rate of plundering and habitat destruction, there will be no more Vallarta mud turtles within three years,” he says.

He adds he’s also frustrated by the unwillingness of the Chinese authorities to crack down on the trade there: “There are photos of collectors with turtles that are marked, other turtles were offered on the pages of an online pet shop in Hong Kong, which is known among experts as a hub for wildlife smuggling, but nothing has happened.”

A smuggler in Hong Kong posing with several smuggled Vallarta mud turtles on a Facebook post. Image courtesy of Turtle Island.

A smuggler in Hong Kong posing with several smuggled Vallarta mud turtles on a Facebook post. Image courtesy of Turtle Island.

The experts we interview agree that if Mexican authorities can’t protect the Vallarta mud turtle’s existing habitats, the only solution will be captive-breeding of the species. Early trials have been promising: when they have shallow ponds with enough seeds, insects, mollusks, small fish, shrimp and snails to eat, Vallarta mud turtles adapt well in captivity.

Guadalajara Zoo carried out the world’s first breeding program for the species in 2023. The NGO Turtle Island has also managed to breed some mud turtles, thanks to donations from European collectors who had brought or purchased a Vallarta mud turtle long before its scientific description as a distinct species in 2018.

“Females lay one to four eggs, two to three times a year. If all goes well, you could optimally produce around 300 animals per year in captivity“, Blanck tells Mongabay. “It is not the best solution, as our mission always is to preserve the species and release animals back into the wild.”

Experts say they hope that in the future there will be an opportunity to do that; but if more of the habitat disappears, they warn, there will be no other option.

Banner image: Scientists only described the Vallarta mud turtle as a distinct species in 2018. The males have a yellow spot on the nose. Image courtesy of Nadin Elizabeth López González.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.