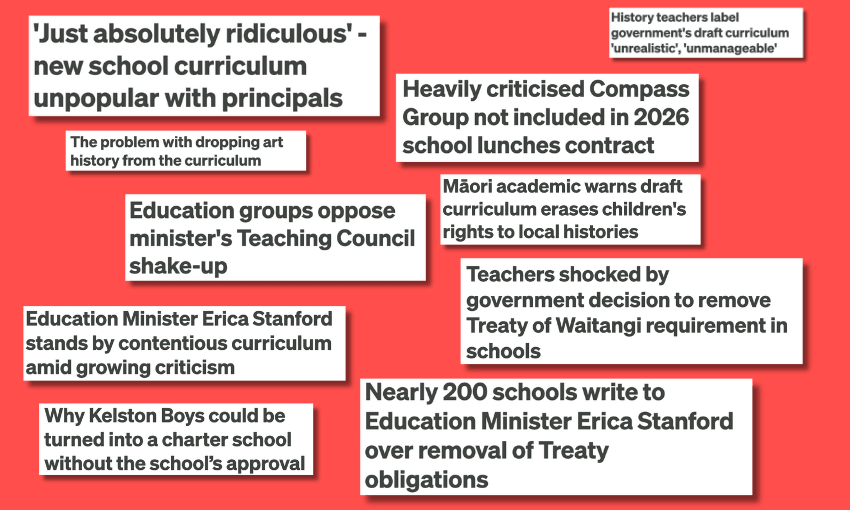

Struggling to get your head around the recent barrage of education-related headlines? Here’s a rundown.

You’d be forgiven for losing track of the education news whirlwind currently ripping through the country. Reforms, last-minute legislative tweaks, surprise contract announcements and controversial governance changes, the effects of which reach into every corner of school life – from what kids eat at lunchtime, to what they learn in class, to how school boards operate, to how teachers are trained.

Each change has been made even more discombobulating by the various offshoots of commentary, confusion and frustration. It’s all unfolding upon the foundations of an industrial dispute between the government and teachers that contributed to one of the largest worker strikes in this country since 1979. In short, there is an awful lot going on in this country’s schools. So, in case you blinked, here’s a rundown of the recent education changes worth having on your radar.

Haere rā to NCEA

After more than two decades of loyal service, NCEA is being sent on its merry way, the government announced in August. Consultation closed in September and the final shape of the reforms remains to be seen, but the plan is essentially to retire the old qualification system for students in years 11-13, and roll out a shiny new model which will be phased in over the next five years.

Under the proposal, year 11 students will get a “Foundational Skills Award” with compulsory English and mathematics. Year 12s will move to the New Zealand Certificate of Education (NZCE), while year 13s will graduate into the even fancier-sounding New Zealand Advanced Certificate of Education (NZACE). The grading system will also get a facelift: goodbye Achieved, Merit and Excellence, hello A to E grading scales. Students will need to take five subjects and pass four of them (with fewer subjects to choose from); and, tragically, there will be more end-of-year exams (marked with the help of a bunch of AI examiners).

A collection of around 64 principals from schools like St Kentigern College, Auckland Grammar and Epsom Girls’ Grammar have urged the education minister to go ahead with the plans, calling the reforms “a powerful antidote to a trend of student underachievement”. But around 90 principals from largely lower-income communities, plus Te Rūnanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa, which oversees kura kaupapa, have given the changes a very solid Not Achieved, calling for an immediate pause to the proposal. They have cited concerns with reform overload in the case of NCEA and parallel reforms across both primary and secondary schooling.

Prime minister Christopher Luxon and education minister Erica Stanford (Photo: Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

Secondary schools get newly minted subjects and a curriculum shake-up

Speaking of parallel reforms, the first step in the winding up of NCEA is the launch of a newfangled curriculum in 2026, followed by a parade of fresh school subjects to be phased in (and out). Education minister Erica Stanford introduced a lineup of “industry-led subjects”, pitched as giving “students more choice”, in September. Those mentioned include AI; Earth and space science; statistics and data science; electronics and mechatronics; civics; politics and philosophy; media, journalism and communications; te mātai i te ao Māori; Pacific studies; music technology and new specialist maths subjects including the ominous-sounding “further maths”. Conspicuously missing from the subject list was art history – a decision that has sparked a fair amount of backlash. And concerns have been raised about the potential privatisation of the planned “industry-led” subjects. Draft Ministry of Education-led subjects for years 11-13 will be released in term 1, 2026 for feedback, with the development of subjects led by various industries to begin at the same time.

The sweep of changes has continued into this week. The Education and Training (System Reform) Amendment Bill was introduced to parliament yesterday, having its first reading last night. It would give the minister of education more influence over changing the curriculum, including the power to create alternative versions of the curriculum for different student groupings or school types.

The primary schools curriculum also gets a makeover

Confusingly, there’s a whole other curriculum change going on. In late October, the full draft of the curriculum for year 0-10 students, to be phased in across three years from 2026, was released. Stanford called it a “significant step” towards a “world-leading system for every learner”.

The reception in school staffrooms across the country has been less positive. The Principals Federation, Te Akatea (the Māori principals and leaders association), NZEI Te Riu Roa (the primary teachers’ union) and an assortment of subject associations – science, technology, social sciences, languages, arts, drama, health and physical education and more – responded in unified frustration.

Critics say the draft curriculum is old fashioned, too prescriptive, consists of an unrealistic number of learning objectives, sidelines te Tiriti o Waitangi and Māori knowledge, appears to be written by foreign contractors and seemingly ignores teachers’ previous recommendations. The new and finalised maths curriculum was a particular focus of consternation. It’s the third reincarnation of the maths curriculum in three years and schools had already rolled out an updated model earlier this year, only to find a new, out-of-the-blue finalised version with significant tweaks included as part of the announcement – rendering months of work this year to bring in the last edit essentially pointless. Principals Federation president Leanne Otene said the latest rewrite pushed principals past the point of revolt. That mood is reflected in a recent NZEI survey of 228 principals which found that although, positively, 84% were pleased with the strengthened focus on literacy and numeracy in the curriculum, over 80% rejected the process and the timeline for developing the curriculum, and, perhaps mostly gloomy of all – 73% said they were likely to quit within the next five years because of changes in workload and wellbeing.

Photo: halbergman via Getty Images

The country’s founding document is now optional for school boards

As part of the government’s wider review of Treaty clauses in legislation, last week, amendments to the Education and Training Act that remove the requirement for school boards to give effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi were quietly passed at the 11th hour. Significantly, this happened without any broad consultation with the public or Ministry of Education, or with Māori, for that matter. In fact, it was instead introduced after consultation had closed.

The now removed Treaty requirement in the Education Act said school boards were obliged to give effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi by ensuring plans, policies and curriculum reflected local tikanga, mātauranga and te ao Māori; by taking reasonable steps to make instruction in tikanga Māori and te reo Māori available; and by achieving equitable outcomes for Māori students.

Originally, the government had been progressing a softer amendment that would alter the Treaty objective to one achieving equitable outcomes, and replacing references to local curriculums reflecting local tikanga, mātauranga and te ao Māori with “teaching and learning programmes”.

The fallout from the more radical amendment dropping the entire Treaty requirement has been dramatic. A petition led by the National Iwi Chairs Forum – and supported by NZEI Te Riu Roa, New Zealand Principals’ Federation, New Zealand Post Primary Teachers’ Association Te Wehengarua, Te Akatea New Zealand Māori Principals Association, Secondary Principals Association of New Zealand, Te Whakarōputanga Kaitiaki Kura o Aotearoa/New Zealand Schools Boards Association, Ngā Kura ā Iwi o Aotearoa, and Te Rūnanga Nui o ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa – calling on the prime minister and minister of education to immediately reverse the amendment has gained more than 18,000 signatures. And almost 200 schools have reportedly written to Stanford to protest the removal.

Critics have warned that the change undermines the legal standing of school boards as Crown entities, risks eroding social cohesion; weakens Māori culture and language in schools and shirks the Crown’s responsibility to ensure every learner, including those who are Māori, achieves equitable outcomes. For some, it fits cleanly into what they see as an ongoing and politically-driven pattern of attacks on Māori language, knowledge and culture in schools: cuts to Te Ahu o te Reo, removal of Māori words from early readers, slashed Māori resource teachers – and now this.

Stanford countered criticism of the move by saying that Treaty obligations were the Crown’s responsibility, not schools’. Meanwhile, Act leader and associate education minister David Seymour, a cheerleader of the review into Treaty clauses, called the change “a major step forward”, insisting that boards still had the choice to “teach as much tikanga, mātauranga Māori, and te reo Māori as they like” – the difference being that “the law won’t force them to”. On social media, he lauded the announcement with a post saying “not everyone wants their child’s education to be an eternal marae visit”.

(Image: Facebook)

Teaching Council balance of power tips towards the government

Last week, the government again seemingly united the entire teaching profession in collective displeasure by unveiling major changes to the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand, which registers teachers, sets professional standards and approves teacher education programmes. The reforms were slipped into the Education Training Amendment Bill at the last minute earlier this month, despite the minister having previously shelved a similar proposal after advice from her own officials.

And the shift is no small alteration. Until now, the council’s governing board consisted of seven teacher-elected members and six ministerial appointees. So teachers held the majority. Under the new model, the minister’s appointees will hold the majority: one teacher-elected representative will be booted out of their seat, and that seat will be given to a government appointment – flipping the balance of power away from the profession and towards central government.

Stanford said the overhaul was prompted by a Public Service Commission investigation into procurement and conflict-of-interest concerns at the council, arguing that the shift will lift the quality of teacher training and restore public confidence.

The sector, however, is unconvinced. Ten education organisations – including NZEI Te Riu Roa, PPTA Te Wehengarua, the Principals’ Federation, Te Akatea and several others – sent an open letter on November 9 warning the reforms marked “a fundamental shift in professional autonomy and independence”. Speaking on behalf of signatories, Otene added that no evidence had been offered to indicate how the ministry might outperform the council.

It seems like additional changes are on the cards. The Education and Training (System Reform) Amendment Bill that has just been introduced to parliament proposes shifting a bunch of existing responsibilities from the Teaching Council to the ministry and shrinking the total size of the council to either seven or nine members – again with the majority appointed by the minister. During the first reading of the bill last night, Labour’s education spokesperson Jan Tinetti said the bill marked a “fundamental shift about who has control in education” and

“undermines the independence of the teaching profession”, promising it would be repealed by a future Labour government.

Compass Group gets the chef’s kiss (goodbye)

While the constant barrage of shambolic headlines related to David Seymour’s revamped school lunch programme might have, surely to his pleasure, tapered off, the tales of disastrous, dubious and downright disgusting school lunches being served to school students seem to have stuck in the public consciousness. That might well be why, when it was announced last week that 10 suppliers had been contracted to deliver primary school lunches next year, Compass Group – the multinational at the centre of a year’s worth of edible (and at times, inedible) controversy – was notably absent.

Those suppliers who did gain contracts will be feeding around 52,000 students across 188 primary schools. They include Appresso Pro Foods, Montana Group, Ka Pai Kai, KDJ Catering, Café Mahia, Star Fresh, the University of Canterbury Student Association, Knuckles, The Y Gisborne, Pita Pit and Subway. Another development is that these local and regional providers will operate under a slightly higher per-meal allowance, with some able to charge up to $5 per meal – a whole $2 more than Seymour’s initially budgeted $3.

Compass Group, however, has not been fully ejected from the school lunch kitchen. The company remains locked into a separate two-year, $85m-per-year contract to churn out $3 lunches to around 51% of the country’s intermediate and high schools as leaders of the School Lunch Collective. That contract, which began in term 1 of this year, has been plagued by troubles: inconsistent portions, late or missing deliveries, undisclosed funding top-ups, questionable recycling claims, food-safety mishaps, nutrition complaints, diminutive portions, “vegan” dishes with beef, “halal” meals with ham, plain “gross” meals and the collapse of partner Libelle Group in March. Oh, and then there was the case of the student who was sent to hospital by an “exploding” cottage pie.

With the auditor-general now investigating the entire alternative provision model for the lunches, critics said the shift back to local providers for primary schools was a necessary course correction. Child Poverty Action Group called the change a “huge win for tamariki and their communities”, while urging the government to restore the original $8 meal funding.

(Image: Reddit)

Turbulence on the charter school front

Charter schools have surged back into the headlines over the last month – and not always for especially auspicious reasons.

Spurred by the $153m Budget 2024 push to establish 15 new charter schools and convert 35 state schools, a fresh batch of charter schools has been recently confirmed for launch next year: the online-based Aotearoa Infinite Academy, Autism NZ Education Hub, Te Aratika High School in Hawke’s Bay, Sisters United Academy, Altum Academy in Wellington and Upper Hutt sports academy. This brings the total number of new charter schools to 17, exceeding the originally indicated 15.

But the rollout hit a slight snag last week when it emerged that the Charter School Agency had, in the establishment of an Upper Hutt sports academy charter school, signed a contract with a trust that did not actually exist. Associate education minister David Seymour labelled the incident “a bit of a screw-up”, which is one way to describe a legally questionable deal with an imaginary organisation. Even so, the school is set to go ahead.

Meanwhile, the state-to-charter conversion process has also had some issues. Although applications closed last week (with two unnamed state schools approved beforehand), the most headline-grabbing development has centred around the uniquely weird Kelston Boys’ High saga. A West Auckland charity by the name of Bangerz Education and Wellbeing Trust joined forces with a former board member to lodge what has been described as a “hostile takeover” bid to convert the school. The episode revealed that nearly anyone can, in fact, attempt to take over an existing school – a revelation that seemingly came as a surprise to many, including the school itself. In response, acting principal Daniel Samuela told parents and the wider community that the proposal was neither “endorsed” nor “supported” by the school.