In recent years, New Zealand politicians have proposed a lot of big stuff but achieved far less. If they actually want to build things again, they may need to think small.

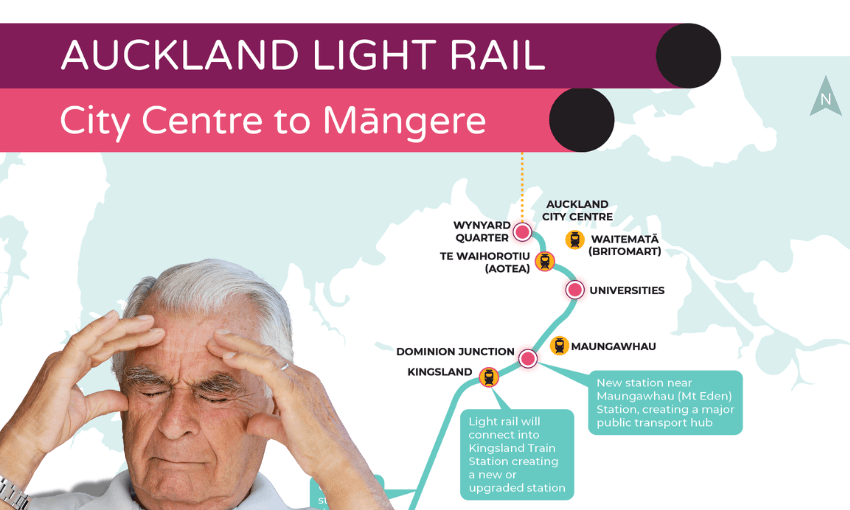

Grant Robertson was bullish as he announced Labour’s plan for a partially tunnelled light rail line to Auckland’s airport. The cost was eye-watering: about $15bn by the government’s figures. As high as $30bn by Treasury’s. But the finance minister insisted a huge, city-shaping investment was needed to “future-proof” Auckland’s transport system. “We are not going to repeat the mistakes of ad hoc planning and a scramble to build infrastructure when it is too late,” he said.

That was 2022. We know what happened next. Another year of reports. Roughly $230 million spent. Not a metre of track laid. When National came to power, it promptly euthanised the light rail plan before throwing its corpse unceremoniously into a ditch marked “money for big roads”.

At least Auckland light rail (2017 – 2023 RIP) has company in its final resting place. New Zealand’s political history is littered with abandoned and stalled megaprojects. When Labour came to power in 2017, it dumped a bunch of expensive motorways, including the East-West Link and the Pūhoi to Wellsford highway extension. Let’s Get Wellington Moving was meant to reshape the capital’s entire transit network. It built one traffic crossing in four years. Robbie’s rail would have been a massive overhaul to Auckland’s transport system if it wasn’t summarily dumped into the bin by Robert Muldoon. Politicians are now in their third decade of trying to build an extra Waitematā Harbour crossing, and may well be trying for at least three decades more.

Some of these projects fall victim to political opposition. Others descend into a kind of rabbit hole of business cases and reports as officials try to grapple with the sheer scale of the task before them. But all of them suck up huge amounts of resources and time while achieving somewhere between almost nothing and nothing at all, and as a result, New Zealand can feel completely paralysed. While we angst our way through 15 different route variations for a single light rail line or churn out investment cases for what will likely be an $18bn-plus highway to Whangārei, other countries just get on and build thousands of kilometres of high-speed track.

Given their at-best patchy record, why are our politicians and officials so addicted to megaprojects? Auckland’s mayor Wayne Brown has a blunt diagnosis. “Sometimes big projects are necessary to get a city functioning well, but too often politicians use them as a namesake to make their mark. Gold-plated, over-designed megaprojects are very rarely needed,” he says.

Green Party transport spokesperson Julie Anne Genter agrees. She says politicians love cutting ribbons on new megahighways when we’d all be better served by smaller investments. “It’s a political economy problem,” she says. “It’s easier to campaign on and claim credit for a few big projects – but those are not usually the best use of public money to get the outcomes we want.”

Transport minister Chris Bishop doesn’t think that’s a fair characterisation. Though megaprojects get the headlines, he points out that 96% of the projects in our infrastructure pipeline have a budget of under $50m and 98% have a budget of less than $100m. “It’s the high-profile, high-cost projects like Auckland Light Rail, Lake Onslow, and Let’s Get Wellington Moving that make the headlines. But it’s the low-profile and often low-cost projects that actually make New Zealand,” he says.

Bishop could add some of the government’s roads of national significance to that list of headline-grabbing big ticket items. In a recent speech to a roading industry conference, he admitted the cost of the 17 routes National has committed to has blown out to $56bn, and many won’t be built for many years to come. The Infrastructure Commission Te Waihanga estimates one of the roads alone – the highway from Pūhoi to Whāngarei – could take up 10% of the entire national budget for new infrastructure for the next 25 years.

Some politicians don’t think the cost is sustainable. When he’s not chucking road cones around, Brown can be found haranguing officials to get more out of existing infrastructure. He thinks the cheapest solutions are often the best. “It’s easy to become distracted by government-imposed megaprojects which opposition parties promise in an election-year brain fart,” he says. “These divert attention from simple fixes for our daily lives like getting traffic lights to flow better.”

Wayne Brown can often be spotted carrying out violent retribution against his hated road cones.

Brown and AT’s chief executive Dean Kimpton have had their disagreements, mainly over the aforementioned cones, but on this, they’re perfectly aligned. Kimpton says we’ve fallen into a habit of “ubering projects up and up and up” to include everything, when we’d be better starting small and expanding from there. He thinks light rail “fell over under its own weight” and believes we might not be stuck with nothing if the government had got on with laying some surface-level track on Queen St back when AT suggested it in 2015. “I think a lot of infrastructure investment is about momentum, not just about designing the ultimate solution,” he says. “So if there was one lesson learned, it’s ‘don’t think you have to have the ultimate solution’. You can have direction, but build it out and use momentum to help you get there, and it will deliver every time.”

In other words, wanting to “future-proof” projects may be understandable, but it’s often counterproductive. Greater Auckland’s Matt Lowrie says we end up spending billions of dollars today to “stop someone standing on a platform in 2070” when we could be getting lower cost projects underway and leaving the business of expanding them for later. He points out the projects that have been built in recent decades, including Auckland’s rail and motorway networks, have been constructed in stages. “But all the stuff that we’re seeing now is building 30 kilometres of State Highway in one go or a whole rail line in one go,” he says. “We’ve got to plan it for 100 years, and so now it’s got to include stuff that we might not need for 99 of those years.”

Opponents like to cite the decision to build the Auckland Harbour Bridge with only four lanes in the 1950s as an example of the dangers of thinking too small. But starting with an undersized bridge and expanding to eight lanes a decade later arguably produced a better outcome than if politicians had stuck with the five lanes initially proposed, says Lowrie. “We’ve now got more capacity than what we would’ve had if we had just tried to go with what was originally planned.”

We also have, on the most basic level, a bridge. When Labour announced its headline transport policy ahead of the 2023 general election, it was met with a chorus of boos. The party wanted to spend $44bn building two road tunnels under the Waitematā Harbour, along with a light rail line through seabed sludge, the toilets of the Belmont McDonald’s and most horribly of all, Albany.

Lowrie called the plan “farcical”. The Herald’s Simon Wilson accused the party of being transport “fantasists”. Labour transport minister David Parker defended it as a multi-decade, phased investment. He may have been right, technically, but no-one believed him after the party’s light rail saga. The thing with megaprojects is they’re such huge, long-term ambitions, they look in practice like nothing, a hazy vision on the horizon never materialising in the real world, and what would you call that except a fantasy? Eventually it comes time to snap out of it.