Seven years ago, a young sculptor from Varad village in Malvan was asked if he could craft two unusual wooden figures – the heads of the mythological serpent Vasuki and a peacock. For Kunal Joshi, the challenge was two-fold: he was unfamiliar with wood and he had no clear idea what these animal heads were meant for.

“I thought they were to be used as mementos or show pieces,” he said.

It took him six months to painstakingly chisel away at blocks of Burma teak to shape the figures and dispatch them. Only months later did he learn their purpose: they were to bookend a priceless old rudra veena belonging to Bahauddin Dagar.

The musician was seeking to restore the instrument once owned by his father and was crafted in 1960 in Calcutta by the master luthiers Kanailal and Brother. His father, the rudra veena legend Zia Mohiuddin Dagar, had redesigned the rudra veena to produce a lower octave that would match the human voice. To this, he added the beautiful end pieces for a reason: the Vasuki would reduce tension on the strings, while the peacock head would contain a chamber, allowing for greater resonance.

“I could find no one to restore the veena and thought that I could start by just getting the Vasuki and peacock made and then see if its maker could go further,” recalled Dagar.

Joshi would uncover all this only when he landed up at the ustad’s dhrupad gurukul in Panvel. This was in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic had forced him to extend his stay there and the magic of the veena – its profoundly deep bass resonance – drew him into a study of the instrument’s sound and structure. Over the next two years, guided by Dagar, he learned to deconstruct and then reconstruct the veena step by step. Today, five veenas owned by Dagar’s students are Joshi’s handiwork, and he now offers Dagar-style veenas to any musician seeking one.

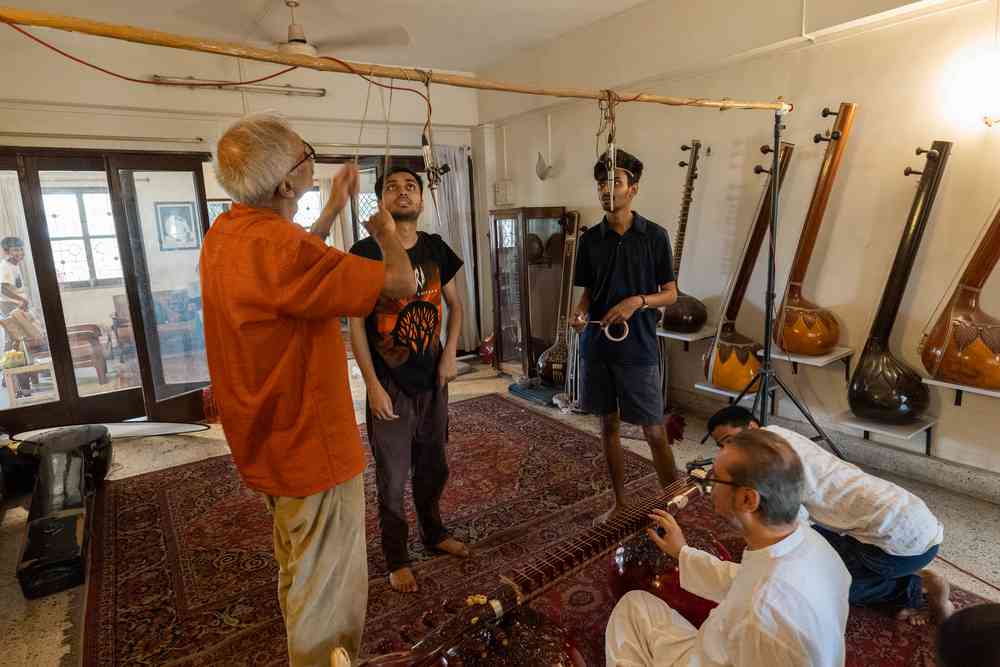

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

The story of this remarkable creative journey – where art, material, music and the science of sound came together under a master musician’s innovative mentorship – is the subject of the short documentary The Shape of Sound. Produced by the Film and Television Institute of India, it is directed by renowned sound engineer and designer Madhu Apsara, who has collaborated with Dagar for over two decades.

Why this experiment became necessary is, in itself, a fascinating story, one that traces back to the rare and precious nature of this instrument. Known to be notoriously hard to master, the rudra veena has counted only a handful of true practitioners at any point in history. Extinction always looms close, not just for the art, but for its making as well. Today, with one or two exceptions, most of the old master luthiers have stopped crafting the rudra veena.

“The whole project came from my fear that there will be no veena makers left,” said Dagar, an eclectic artiste with varied interests and a young, dedicated following. “I needed someone to join my journey to find an avenue out of the crisis by mentoring fresh talent in the art. Kunal was a godsent and some of my other students are learning the craft as well. In fact, Shibu Maity, who has been cooking for my household, is now an expert at filing the bridge.”

For Joshi, it was a revelation to move from being a sculptor to an instrument maker, discovering how lifeless material could become a vessel for exquisite music. “There are so many more details to pay attention to while crafting the veena, nearly 70-80 parts to put together,” he said. “The smallest error can be ruinous. But a good instrument produces a sound that can give so much joy, like watching the badmast chaal (swagger) of an elephant.”

Magical spell

The Sufi Inayat Khan Dargah sits in the heart of Delhi’s Nizamuddin basti, an oasis of quiet amid the bustling neighbourhood. Every three months, on the fifth of the month, Bahauddin Dagar offers a recital as a hazri at the shrine. It is a recital without percussion, allowing you to hear the delicate musicality of the veena, a practice that Dagar favours.

The rudra veena has always carried an aura of high mysticism. An entire world of myths, miracles and superstitions surrounds it and practitioners still subscribe to these beliefs to varying degrees. Some of its most renowned legends were men of deep spiritual inclination across faiths – Dattatreya Rama Rao Parvatikar, Shamsuddin Faridi Desai, and Bande Ali Khan, among them. Contemporary artists of the form firmly believe that the art has yogic and intangible dimensions, extending beyond the purely physical and material.

At the dargah, Dagar plays a raga Malkauns that is remarkably sublime. In an age when instrumentalists often chase ear-splitting volume to impress, he prefers to keep it low, letting the veena weave its mellow magical spell.

“In the old days, the veena was played in massive interiors of palaces, temples and forts, the sound travelling across and bouncing off stone, beams and arches,” said Dagar. “It may be soft but it has a lot of resonance and overtones and a certain circularity that could carry across distances. It is a sound that does not die easily.”

It is a sound ethic that Madhu Apsara understands and translates perfectly for Dagar. A student and longtime associate of the musician, he is deeply attuned to Dagar’s philosophy of how the veena should sound on stage. For at least 25 years, they have worked together to ensure that amplification does justice to the veena’s unique tone. It was this partnership that inspired the sound engineer to shoot the 20-minute film documenting the collaborative experiment between Dagar and Joshi.

“It [The veena] is a quieter instrument, and [its] sound is very tender, so it needs faithful amplification and reproduction to retain the original microtonal clarity,” said Apsara. “We keep the volume purposely low so that the nature of the instrument is retained. This also quietens the mind of the listener so they start hearing the nuances. We do this even in big concerts. Silence is very important in our music.”

Lofty stature

Apsara’s film documents an interesting aspect of Dagar’s work with his instrument. With the near-disappearance of legacy veena makers, it is those from non-musical backgrounds who are preserving the craft – Joshi, Maity and Apsara, among them.

There were once dedicated pockets of veena-making expertise across India, primarily in Vadodara, Meraj and Calcutta. Names like Kanailal, Mangala Prasad and the Mistry family are among the most renowned in the field. But it is not an easy craft to sustain: it takes at least two years to craft a single instrument, and with declining performers and audiences, demand has dwindled.

“Kanailal stopped making the veena and I had no one to turn to when I wanted to restore my father’s veena,” said Dagar. “Many makers also bought into the superstition that if they make a flawed veena, their families would be cursed.”

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

By the 1990s, finding a maker had become nearly impossible. As a result, many veena players had no choice than to become adept at making and repairing instruments, as 55-year-old Dagar learned early in his life.

Like many youngsters rebelling against the weight of a colossal legacy, Dagar had not immediately taken to the veena, even though its sound filled the 1-BHK Chembur family home. He began his musical journey on the sitar, learning under the tutelage of his mother, Pramila Dagar. As a teen, it was rock, jazz, and pop that captured his imagination. “I would play that at loud volumes, and my father was not the forceful type – he let me be,” he recalled. “But I was intrigued by the sound of the veena.”

The Dagar home was an adda for eclectic discussions on films, quantum physics, architecture and art. Mani Kaul’s famous 1982 film Dhrupad primarily featured Zia Mohiuddin and his brother, vocalist Zia Fariduddin Dagar. Kumar Shahani’s experimental film Khayal Gatha featured Zia Mohiuddin’s work too.

“It was only after my father passed away in 1990 that I started looking at what he gave me and put myself into serious practice,” he said. In his second year of college, he dropped out to pursue the veena with greater rigour. “I was very young, and there were great expectations from me. Do I have what it takes? That question constantly bothered me.”

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

A production still from ‘The Shape of Sound’. Credit: Madhu Apsara.

The journey took Dagar in multiple directions – learning, teaching and delving deeply into the structure of the veena itself. “I would do my own repairs because our veena was of a different make. I just had to figure it all out for myself. The circle of veena musicians was so small then – Asad Ali Khan, Hindraj Divekar, Shamsuddin Farid Desai and Bindu Madhav Pathak among them.”

Building a career on an instrument that occupies such a lofty stature is never easy. Critics point out that the veena has painted itself into a corner with its own formidable reputation. These are challenges Dagar is acutely aware of. “It is not as difficult as it is made out to be,” he said. “But I didn’t go out of my way to worry about what the audience wants. I care for the nuances and how I choose to unfold a raga may or may not be received well. So I played a few concerts, taught, held workshops, got some scholarships and fellowships. [I] managed somehow.”

It was around five-seven years ago that interest in the rudra veena began to grow, along with Dagar’s own following. Performers like him and Jyoti Hegde – the first woman to take up an instrument once considered too powerful for women – are now far more visible than before, and their students are steadily increasing.

“I can imagine a time in near future when the veena will be in greater demand, when the fortunes of the few makers in the market will revive,” said Dagar. “When they will promise an instrument in six to seven months. Who knows it may even come off the shelf. That is the cost of popularity.”

As for Joshi, this journey of discovery has been exhilarating. It is a slow process, but one he relishes – from picking up the kadwa kaddu (bitter pumpkin) that grows mostly in Pandharpur to crafting the rotund resonators at either end of the instrument, to sourcing teak wood for the dandi or fingerboard, hollowing out the wood, carving, finishing, polishing, and affixing the two animal heads. The frets are installed by Maity, while the ustad steps in to oversee the stringing.

“When I was restoring the tumba of Kanailal’s perfect veena from 1960, I saw that the artisan had left one flower carved but without any detailing,” Joshi said. “I was taken aback and then it struck me – imperfection leaves us with a path forward. Anything that is perfect tends to be dead.”

Malini Nair is a culture writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She can be reached at writermalini@gmail.com.