Mammal embryos show differences between individual cells from the very first division — a finding that could transform stem cell therapy, Northeastern University researchers have discovered.

Individual cells are distinct from one another in mammal embryos from almost the very beginning of life — the first division of cells — overturning a long-held belief that human embryos are a blank slate until later in development, Northeastern researchers report.

“People assume that in those early stages, the two cells are much more similar to each other,” says Nikolai Slavov, bioengineering professor and director of Northeastern’s Single-Cell Proteomics Center. “It wasn’t known how they’re different, and we have found molecular differences that can predict their developmental potential.”

The findings may guide future research in regenerative medicine, Slavov says. The cells more likely to develop into a viable embryo contain certain proteins that could “become targets to improve reprogramming efficiency or embryo-like formation from stem cells,” he says, to make them more medically effective.

The findings were published today in the journal Cell.

Using a powerful machine learning-enhanced technique called single-cell proteomics by mass-spectrometry to measure proteins in individual cells, researchers in Slavov’s lab identified proteins in a two-celled embryo that varied abundantly from one cell to the other and that those differences related to the organism’s future success.

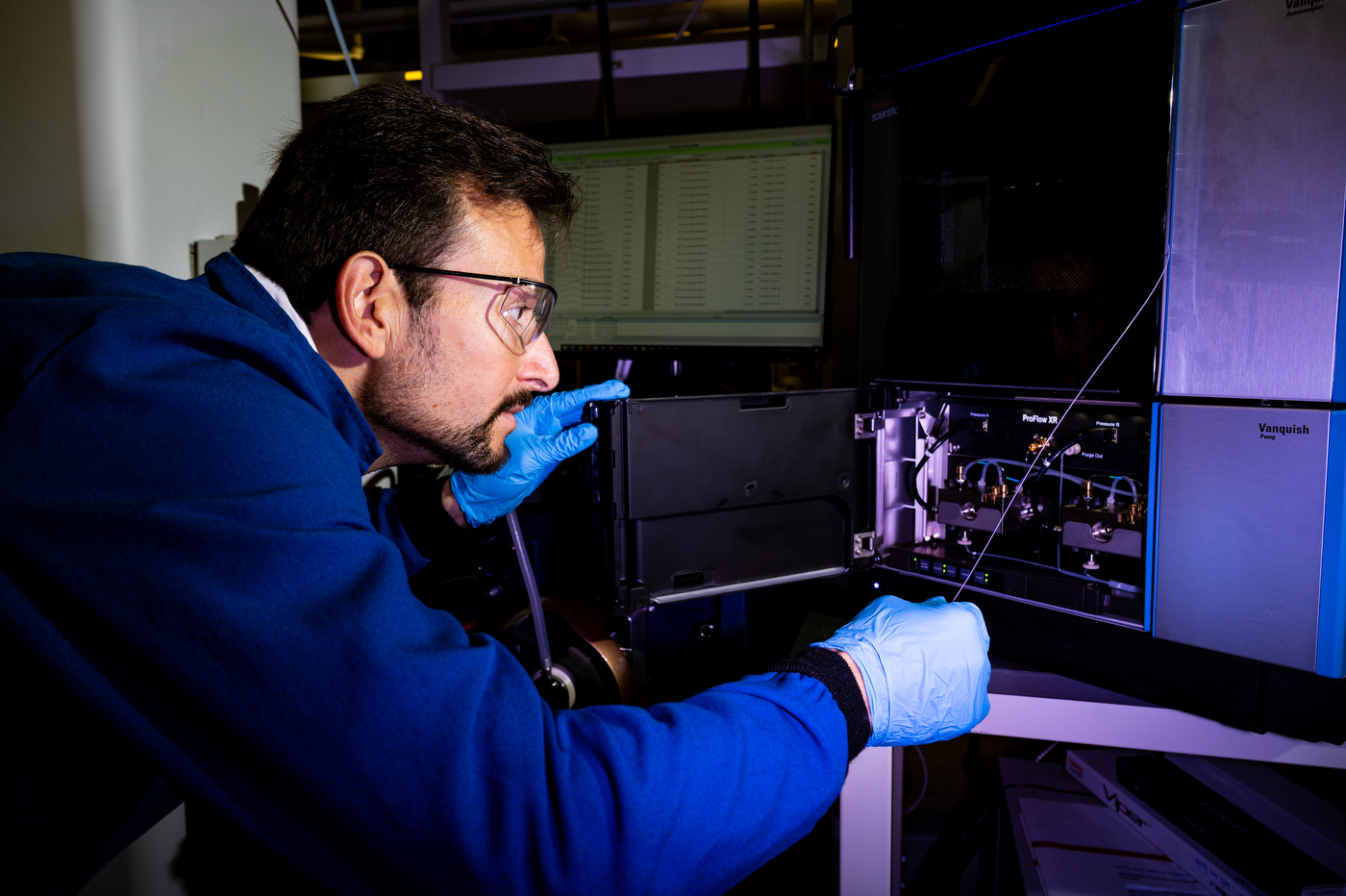

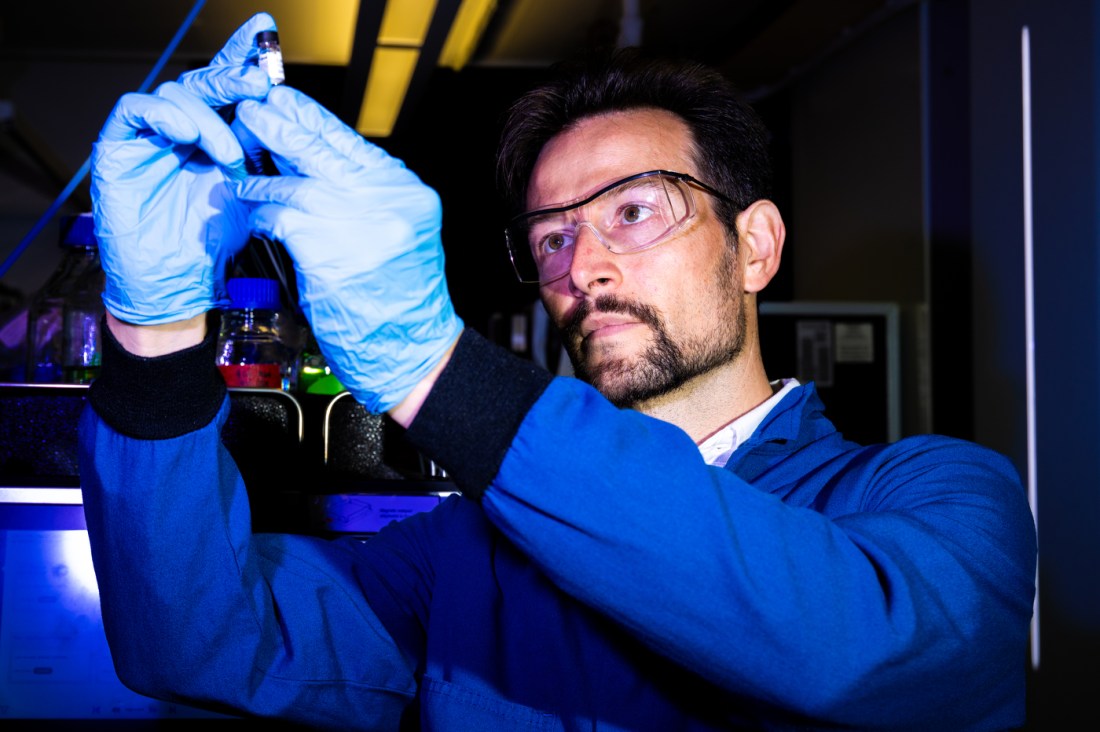

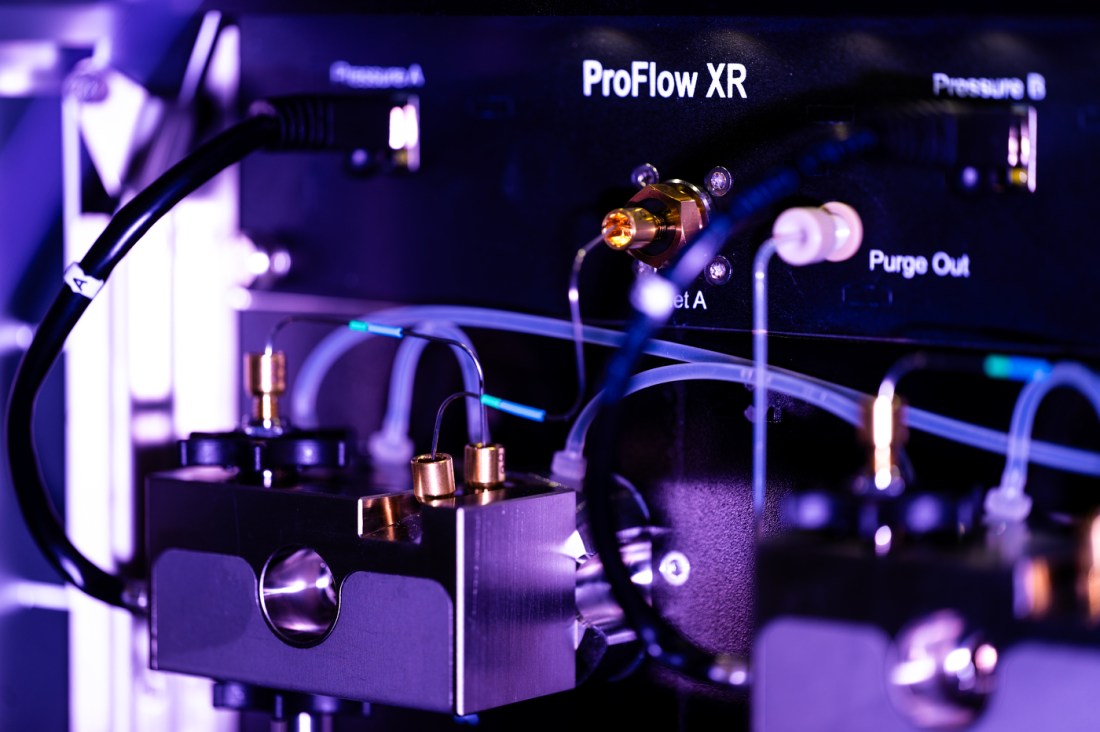

09/25/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Nikolai Slavov, Northeastern professor of bioengineering, works on single-cell proteomics in his lab in the Mugar Life Sciences Building on Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

09/25/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Nikolai Slavov, Northeastern professor of bioengineering, works on single-cell proteomics in his lab in the Mugar Life Sciences Building on Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

09/25/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Nikolai Slavov, Northeastern professor of bioengineering, works on single-cell proteomics in his lab in the Mugar Life Sciences Building on Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

09/25/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Nikolai Slavov, Northeastern professor of bioengineering, works on single-cell proteomics in his lab in the Mugar Life Sciences Building on Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

The findings may guide future research in regenerative medicine, says Nikolai Slavov. Cells that are more likely to develop into viable embryos contain proteins that could improve the efficiency of stem cells, he says, and make them more medically effective. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

The differentiation of initially identical cells, says Slavov, is driven by proteins. It happens earlier than was previously understood, but one of the cells is more likely to develop into a viable embryo.

The proteins are key to the discovery, Slavov says. The proteins in our cells are complex molecules that orchestrate complex chemical reactions, from growing tissue to fighting disease. Our bodies house thousands of different types of cells, which contain tens of thousands of different proteins, he says.

But it has been difficult for medical researchers to assess the potentially infinite number of proteins responsible for biomechanisms involved in crucial functions. To capture single cell protein levels accurately, says Slavov, requires scientists to increase the number of analyzed protein copies to tens, hundreds, and thousands.

In 2018 Slavov and his team developed technology using mass spectrometry, a technique bioengineers have progressively used in detecting and differentiating proteins, to identify more than a thousand proteins in an individual cell. The team later revamped the technique with data-driven methods, enabling them to identify over 2,000 proteins in a cell.

In this new research, they were able to measure different proteins simultaneously and compare them between cells, revealing differences that previous methods had missed.

The results were initially found in two-cell mouse embryos but were found again in experiments on human embryos.

It is already understood in biology that the embryonic cells of other species are different from the start, Slavov says. Fish and reptile cells, for example, have a “pre-pattern” or subtle blueprint from the first cell division after fertilization.

But the early cells for mammals, including humans, were thought to be identical and flexible, meaning they could go on to become any part of the organism, he says. Contributing to this understanding was that when cells in a mammalian embryo are damaged or removed, the remaining cells can compensate and form a complete organism.

“We can separate the cells and then we can grow one of them and see whether it develops into a viable embryo and how that future developmental potential is associated with the protein differences that we measured,” Slavov says. “We found that the protein differences are predictive of the developmental potential of that cell.”

Northeastern Global News, in your inbox.

Sign up for NGN’s daily newsletter for news, discovery and analysis from around the world.