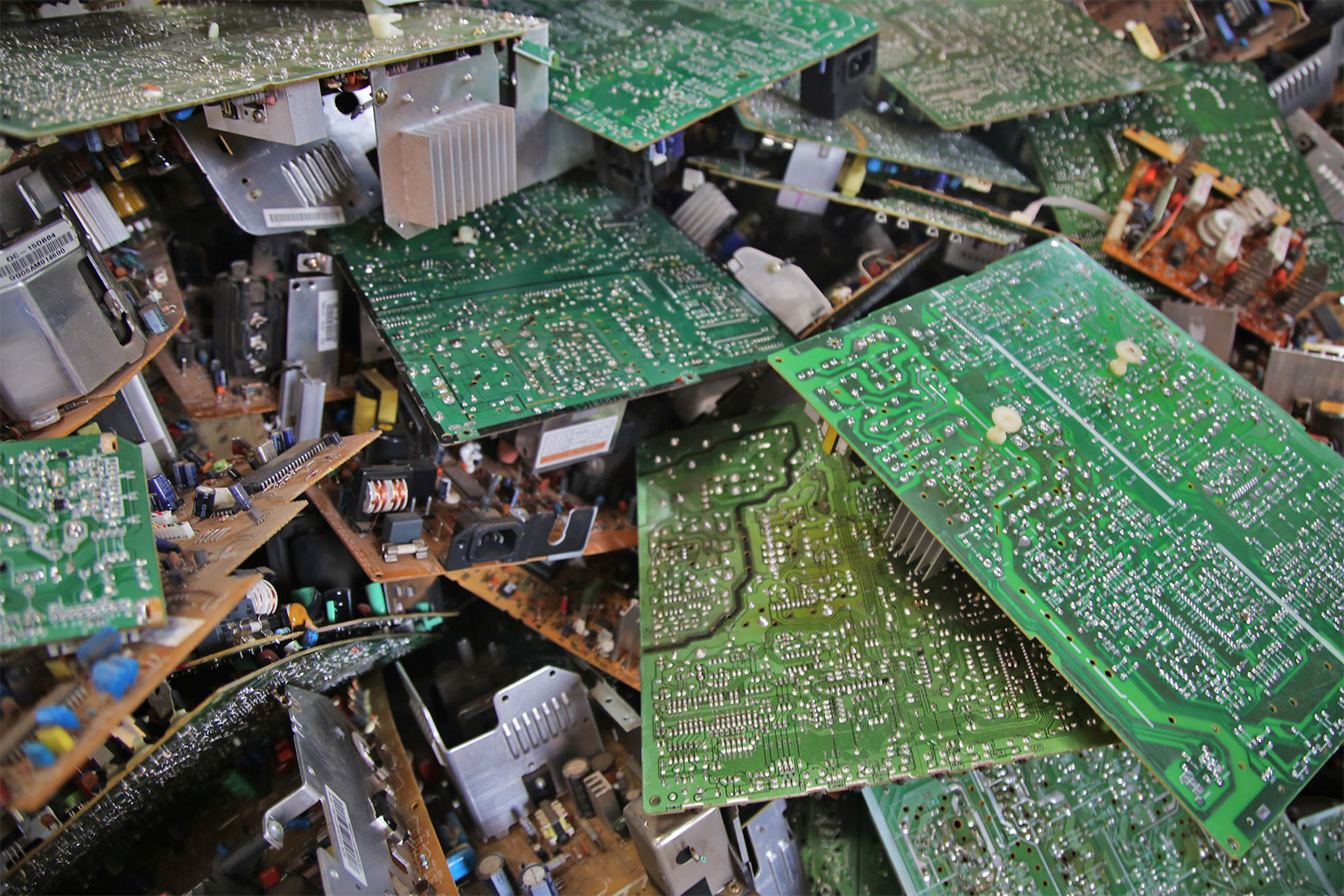

E-waste, which refers to discarded electrical or electronic devices, is the fastest growing domestic waste stream in the world, and it is highly toxic, threatening public health. Much of this e-waste, largely produced by rich countries, is dumped in poor countries, with Asia and Africa major destinations.Because poor countries mostly lack the highly sophisticated equipment and processes needed to dismantle and recycle these complex composite products safely, unskilled scrap workers, including children, plunder them for resalable components, often with a disastrous impact on their health and the environment.Increasingly, the torrent of discarded cell phones and obsolete computers is greatly exacerbated by invisible e-waste: a vast, varied plethora of microchip-containing products, ranging from vaping devices to e-readers, toys, smoke detectors, e-tire pressure gauges and chip-containing shoes and apparel.Invisible e-waste greatly adds to developing world recycling challenges. The U.N. Environment Programme warns that “the increasing proliferation of technological devices has skyrocketed the amount of electronic waste worldwide” with nations now facing “an environmental challenge of enormous dimensions.”

See All Key Ideas

“I live in Accra, Ghana,” says Isaac Dinwe, who works for Closing the Loop, a Dutch NGO that’s seeking to increase recycling in the electronics industry. “The e-waste problem in my country is so huge we are unable to manage it. Most of our e-waste ends up in city centres. Informal workers extract what they can sell and burn the rest. It causes a lot of pollution,” Dinwe writes in an email to Mongabay from the group.

Dinwe is one of a handful of Ghanaians tackling a public health and environmental crisis brought on by the global consumer economy and a lack of legislation and infrastructure around the globe. Dinwe heads a team trained to properly handle e-waste and travels to repair shops, villages and churches to buy “dead” phones that would otherwise end up landfilled or burned. “We are careful not to pay too much, as we want the phones to be used right up to the end of their life,” explains Closing the Loop CEO Joost de Kluijver.

Isaac Dinwe, a Ghanaian, heads a team of 16 people who buy ‘dead’ phones cheaply from repair shops and elsewhere in Accra, Ghana, to prevent them from being tossed into landfills. But, despite the team’s work, a lot of e-waste ends up in waste dumps where scavengers extract salvageable bits, then burn the rest, causing pollution that threatens public health. Image courtesy of Closing the Loop.

Isaac Dinwe, a Ghanaian, heads a team of 16 people who buy ‘dead’ phones cheaply from repair shops and elsewhere in Accra, Ghana, to prevent them from being tossed into landfills. But, despite the team’s work, a lot of e-waste ends up in waste dumps where scavengers extract salvageable bits, then burn the rest, causing pollution that threatens public health. Image courtesy of Closing the Loop.

Closing the Loop has joined with phone makers in Germany and the Netherlands to fund the recycling effort. Offering a service called One for One, brands like Vodafone link the sale of their new phones to the retrieval of old ones. Purchasers fund the One for One service by paying a small premium for their new phones — a trend dubbed “waste compensation.”

The exchange program is working: In the case of Vodafone Germany, more than 2.7 million African phones otherwise headed for landfills have been collected since mid-2022.

The scrap phones are sent to Europe for recycling, as Africa doesn’t have a single site, called a smelter, where electronic waste can be processed and metals extracted safely. Closing the Loop, its local partners and the Nigerian government hope to further “close this loop” by opening a smelter near Lagos within two years. That facility, once operational, will be financially sustainable, thanks to the compensation scheme.

Unfortunately, few e-device manufacturers follow Vodafone’s example. Instead, they pursue a profitable linear economic model, taking on no liability for the ecological harm done by their products’ improper disposal. Rather, they pass responsibility on to consumers, who pay trash haulers to cart e-trash away, who in turn often ship it to the developing world to be “recycled.”

A two-year investigation by the Basel Action Network published in October found that a “hidden tsunami” of e-waste is regularly heading from the United States to Asia and the Middle East. “This new, almost invisible tsunami of e-waste, is … padding already lucrative profit margins of the electronics recycling sector while allowing a major portion of the American public’s [e-waste] and corporate IT equipment to be surreptitiously exported to and processed under harmful conditions in Southeast Asia,” the report says.

Street side electronic repairs in Accra, Ghana. Only a tiny percentage of all e-waste is currently recovered for reuse. Image courtesy of Fairphone via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Street side electronic repairs in Accra, Ghana. Only a tiny percentage of all e-waste is currently recovered for reuse. Image courtesy of Fairphone via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

The rising tide of invisible e-waste

E-waste is the fastest growing domestic waste stream on Earth and among the most toxic, with electronic equipment — phones, computers, gaming consoles, modems, monitors and more — predominantly manufactured in the Global North and frequently ending life in the Global South.

Once exported to Africa, Asia and Latin America, this detritus of our everyday lives doesn’t disappear. It’s most often burned in open fires or landfilled, with the toxins it contains easily seeping into soils where crops are grown or chickens raised, into aquifers that serve communities with drinking water, and into the air people breath.

But today, the global e-waste crisis is spreading its invisible toxic fingers far more widely, as microchips (containing toxic metals, plastics and chemicals) are hidden inside a universe of once unimagined consumer products sold on Amazon.com and elsewhere.

Everything seems more exciting and saleable this holiday season if it’s digital: A single mouse click can buy you a season’s e-greeting card (boasting an LCD screen and 128 megabytes of video memory), a digital pet keychain, digital birthday candles, glowing-spinning e-bracelets and blinking e-shoes for children. One big hit this year: a flying LED-lit drone orbit ball with a smart AI chip inside. And there’s the world of children’s e-toys, including AI robots and AI teddy bears (though, consumer groups say, buyer beware!).

A collection of electronic toys. Corporations the world over are always on the prowl for new e-products, AI-gizmos, and e-gimmicks to attract consumers. Much of it may end up as invisible e-waste. Image courtesy of Julianabolico via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

A collection of electronic toys. Corporations the world over are always on the prowl for new e-products, AI-gizmos, and e-gimmicks to attract consumers. Much of it may end up as invisible e-waste. Image courtesy of Julianabolico via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Vapes are promoted year-round as less harmful to health than cigarettes but add vastly to e-waste. According to Material Focus, an NGO seeking to transform the U.K.’s e-waste system, 5 million single-use vapes are thrown away each week in the U.K. alone. The average vape contains plastics, heavy metals, nicotine and 0.15 grams (less than 0.01 ounces) of lithium.

There’s no lack of practical gizmos for adults, including digital pregnancy tests enhanced by microprocessor displays more powerful than early home computers and water jars with carbon filters boasting electronic displays reminding us to change them. Some electronic cables, used to transmit power or telecommunication signals, hold entire chipsets inside. At the end of their life, such cables often end up dumped in an African or Asian country, where children will burn them in huge toxic piles to get at whatever copper or other useful metal hides inside.

“Every year, unused cables, electronic toys, LED-decorated novelty clothes, power tools, vaping devices, and countless other small consumer items often not recognized by consumers as e-waste amount to 9 billion kilograms [19.8 billion pounds] of e-waste, one-sixth of all e-waste worldwide,” the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) Forum stated in 2023. “This ‘invisible’ category of e-waste [if gathered] in one place would equal the weight of almost half a million 40-tonne trucks, enough to form a 5,640 km [3,504-mi] bumper-to-bumper line of trucks from Rome to Nairobi.”

Most of the estimated $10 billion in essential raw materials contained in this “invisible” e-waste stream will never be recovered.

Electrical wires are burned to recover copper at Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Image by Muntaka Chasant via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Electrical wires are burned to recover copper at Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Image by Muntaka Chasant via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

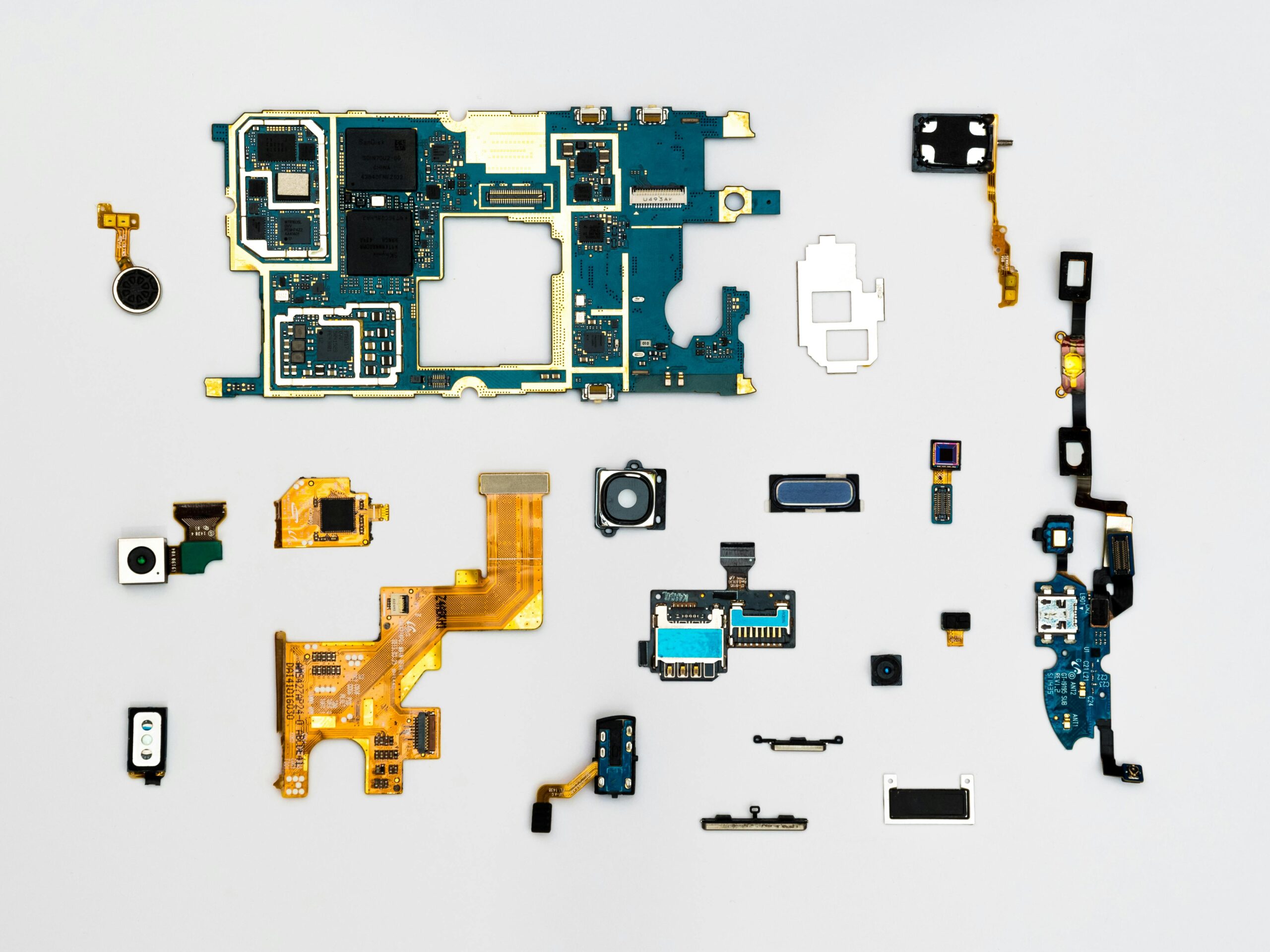

Components of a Sony PlayStation 4 include plastic housing and a variety of electronic components including power supply, optical drive, multilayered custom computer chips, wiring and more. E-devices contain multiple toxins and are extremely difficult to recycle due to their solid state construction. Image courtesy of iFixit PlayStation 4 teardown.

Components of a Sony PlayStation 4 include plastic housing and a variety of electronic components including power supply, optical drive, multilayered custom computer chips, wiring and more. E-devices contain multiple toxins and are extremely difficult to recycle due to their solid state construction. Image courtesy of iFixit PlayStation 4 teardown.

Digital consumerism meets e-waste colonialism

When Silicon Valley emerged in the 1950s, planners were keen to create a sparkling image for a new industry that would make a clean break with the smokestack polluting past. But even back then, it took hundreds of chemicals, some of them toxic, to make a semiconductor chip. And the electronics industry soon turned California’s Santa Clara Valley (once dubbed the “Valley of Heart’s Delight”) into a dumping ground. Today, Santa Clara county has 23 federally designated Superfund sites, the most of any U.S. county.

Over the decades, Big Tech worked its branding magic to convince the consuming public we had embarked upon a clean, green digital age. And as Silicon Valley marketeers likely hoped, today’s exported e-waste stream remains largely invisible in the Global North, though mountain-high dumps of mixed waste sent to the Global South aren’t only visible in poverty-stricken neighborhoods but can also be seen from space.

The 1989 Basel Convention, an international agreement ratified by 191 nations (not including the U.S., Haiti, South Sudan, Fiji or Timor-Leste) was created to control the transboundary movement of hazardous waste. But its lack of global enforcement mechanisms and its uneven implementation by individual member states has greatly reduced its effectiveness.

Add to this the problem of rampant criminality among transnational waste traffickers — with the illegal e-waste trade often being less punishable but just as lucrative for crime syndicates as the illicit drug trade. Organized crime’s links to waste hauling also raise disturbing unanswered questions, including whether unknown quantities of shipped waste could be getting dumped at sea with serious marine impacts.

Sixty-two million metric tons of e-waste were generated in 2022, with 82 million tons forecast for 2030. A growing portion of that waste stream is invisible e-waste found in a vast number of products. Big Tech’s marketing strategy of planned obsolescence adds greatly to this e-waste stream. Image by Rwanda Green Fund via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0).

Sixty-two million metric tons of e-waste were generated in 2022, with 82 million tons forecast for 2030. A growing portion of that waste stream is invisible e-waste found in a vast number of products. Big Tech’s marketing strategy of planned obsolescence adds greatly to this e-waste stream. Image by Rwanda Green Fund via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0).

Some countries have severely restricted e-waste imports. But e-waste exporters find innovative ways to circumvent such rules. A classic approach is to label e-waste as secondhand donations for schools or other institutions. Bribery of port officials has been so common that e-waste container ships traveling the world searching for a place to dock have been dubbed Ships of Doom delivering cargos of “toxic colonialism.”

Asia has until recently been a key hub for European and North American e-waste dumping, with countries there taking enormous quantities. But China, Thailand and, most recently, Malaysia have banned or severely restricted e-waste imports, with Pakistan and India making efforts too — though success has been mixed.

While these restrictions may curb dumping of the most obvious e-waste (eg., phones and computers), it seems likely policing will be very challenged by the flood of invisible consumer e-waste, composed of an astronomical number of video greeting cards, AI stuffed toys and other microchip-containing products.

Electronic waste dumped in India, circa 2011-13. It’s impossible to provide an exact total of accumulated e-waste globally since 1950, as comprehensive data only began to be systematically collected in recent decades. Much of this e-trash is not biodegrade and will persist for centuries. Image by Victor Grigas via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Electronic waste dumped in India, circa 2011-13. It’s impossible to provide an exact total of accumulated e-waste globally since 1950, as comprehensive data only began to be systematically collected in recent decades. Much of this e-trash is not biodegrade and will persist for centuries. Image by Victor Grigas via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The intensifying Africa e-waste stream

With Asia trying to curb e-waste flow, Africa has become a prime target, as many poorer nations have lax regulations and poor enforcement capabilities. Once e-waste arrives in Ghana, Nigeria or other nations, the problem turns toxic. “Recycling” tends to be crude and dangerous because these countries lack the expensive facilities, machines and sophisticated processes required to effectively and safely recycle complex e-products.

Instead, computer motherboards are burned by young people holding Bunsen burners. Cables are heaped in piles and set afire to melt away toxic plastics, with women and children as young as 5 tasked with separating wires because their hands and fingers are small and dextrous. The World Health Organisation warns that more than 18 million children and adolescents are exposed to toxic e-waste globally.

“Huge amounts of [toxic] fine particles are breathed into the lungs of kids,” Andy Farnell, scientist and author of the book Digital Vegan, tells Mongabay. That isn’t the only source of harm. Often young scavengers use bare hands to dip e-waste into nitric, sulfuric or other acids to create a slurry, which is used to extract valuable components. “For instance, gold is extracted by mixing [e-waste with] sodium cyanide to run off gold cyanide,” Farnell explains.

Lots of toxic wastewater results from this process, and the remaining slurry, which is very poisonous and problematic to handle, is dried, then buried or burned. Farnell concludes: “Burying causes terrible leaching 10 or 20 years later, which poisons the land and makes large areas unfarmable.”

The Agbogbloshie dump, near the center of Accra, Ghana’s capital, is among the most notorious digital dumping grounds. Laborers there struggle to process millions of tons of e-waste annually. Scrap workers manually burn heaps of wires stripped from EV auto harnesses and plastic-encased electronic devices to recover copper, while toxins are released unabated into the air, water, and ground.

Local water and soil are contaminated with toxic chemical concentrations vastly above permitted limits. Leaching poisons include lead, mercury, arsenic, dioxins, furans and brominated flame retardants. While there have been piecemeal efforts to mitigate this public health crisis, Bashiru Mohammed, a Ghanaian analyst, says these have largely failed “due to a lack of enforcement, political will and sustainable alternatives for the affected communities.”

The damage isn’t confined to Africa. A study carried out by the University of São Paulo in Brazil identified abnormal levels of lead, cadmium and mercury in the blood of scrap dealers. Nelson Gouveia, who contributed to the research on São Paulo recycling facility workers, notes that burned e-waste creates toxic fumes. “Recycling is carried out with minimum conditions of safety,” he says.

Young men burning electrical wires to recover copper at the Agbogbloshie dump in Ghana. The smoke from such fires is extremely toxic, and can spread on winds far beyond such dumps. Image by Muntaka Chasant via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Young men burning electrical wires to recover copper at the Agbogbloshie dump in Ghana. The smoke from such fires is extremely toxic, and can spread on winds far beyond such dumps. Image by Muntaka Chasant via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

E-waste is the fastest growing domestic waste stream on Earth and the most toxic. Some communities offer e-waste drop-off for recycling as seen here, but how much of this collected e-waste is ever properly recycled is largely unknown, with much shipped from the Global North to Global South which lacks safe processing facilities. Also, invisible e-waste often isn’t recognized by consumers as being potentially toxic and requiring proper recycling so it is disposed of with other household trash. Image by Montgomery County Planning Commission via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

E-waste is the fastest growing domestic waste stream on Earth and the most toxic. Some communities offer e-waste drop-off for recycling as seen here, but how much of this collected e-waste is ever properly recycled is largely unknown, with much shipped from the Global North to Global South which lacks safe processing facilities. Also, invisible e-waste often isn’t recognized by consumers as being potentially toxic and requiring proper recycling so it is disposed of with other household trash. Image by Montgomery County Planning Commission via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

What comes around goes around

It isn’t just recipient countries damaged by dumping. Scientist Eva Garcia-Vazquez has researched and written about “oceanic karma” by which she means that the deeds people initiate can create effects that ripple back and forth between continents and through people’s lives for years.

E-waste offers a case in point. European countries import cobalt and tantalum from Africa, using these hazardous materials to produce smartphones, tablets, electric cars, e-toys and other digital goods.

Once those products become obsolete or wear out, they’re often sent as e-waste to Agbogbloshie and other dumps in Africa. Because these wastes aren’t safely recycled, the toxins they contain — including PFAS and other forever chemicals — if burned can be transported in the wind back to Europe. Or if they end up in landfills, toxins can leach into aquifers and streams, eventually ending up in the sea.

Here they can accumulate in marine sediments, be taken up by plankton and eaten by fish, which may be caught by European trawlers — a heavy metal harvest fishers haven’t bargained on. Those e-waste-contaminated fish could land on European tables, with EU families possibly dining on the toxic remains of smartphones discarded years before.

The end of life for much of the Global North’s consumer e-waste will be a dump or landfill somewhere in Africa, Asia or Latin America. Seen here is a collection of urban dump-mined copper in Ghana. Image courtesy of Fairphone.

The end of life for much of the Global North’s consumer e-waste will be a dump or landfill somewhere in Africa, Asia or Latin America. Seen here is a collection of urban dump-mined copper in Ghana. Image courtesy of Fairphone.

A world drowning in e-waste

The U.N. estimates that just 22% of electronic waste was recycled in 2022. But this is probably an overestimate. That’s partly because claims about recycling effectiveness can arise from marketing propaganda or misreporting. Also, lots of invisible e-waste likely never is identified as such for export and processing. Lastly, just because something gets collected, that doesn’t mean it will be properly recycled.

Compounding the problem: Most modern electronics are not designed to be easily recycled. And with each new generation, they tend to become less so — part of our linear economy and culture of planned obsolescence, in which merchandise is designed to be thrown away and quickly replaced by new, more “efficient” products.

An e-object thrown away today is likely held together with custom screws, strong glues and extensive soldering, making components very difficult to disassemble. Products also contain a vast number of materials, including hard-to-separate alloys, plastics and chemicals such as toxic flame retardants and PFAS.

In 2007, the U.N. Environment Programme warned that global dumpsites posed a serious health threat to those working and living nearby, with toxic chemicals causing cancer, respiratory problems and skin infections. UNEP cautioned that plastic and e-waste contain a cocktail of chemicals disruptive to the body’s hormone systems.

A teddy bear-shaped USB flash drive. As we shop online seeking unique holiday gifts, it’s easy to be seduced by clever and creative e-products. Perhaps we would reconsider our purchasing choices if we recognized that many such items have extremely short useful lives, but they will live on as e-waste far into the future. Image courtesy of Olybrius.

A teddy bear-shaped USB flash drive. As we shop online seeking unique holiday gifts, it’s easy to be seduced by clever and creative e-products. Perhaps we would reconsider our purchasing choices if we recognized that many such items have extremely short useful lives, but they will live on as e-waste far into the future. Image courtesy of Olybrius.

Eighteen years later, environmental organizations warn that “the increasing proliferation of technological devices has skyrocketed the amount of electronic waste worldwide” with the dumping of e-waste “creating an environmental challenge of enormous dimensions.”

In a recent YouTube interview, academic and science broadcaster David Suzuki identified capitalism’s tragic flaw: “Nature, the air, the water, the soil, the biodiversity that allows us to live is not [counted] in the economic system. [Instead, economics is] all based on us” — on people. “Amazon … [the] company, is valued by the economy in the tens of billions of dollars. Amazon, the rainforest, the greatest terrestrial ecosystem on the planet, has no economic value until it is logged, mined, dammed or grows soybeans or cattle or houses. [That’s] a crazy system!” The outcome of this modern conundrum: Maybe only one Amazon can survive.

That’s food for thought the next time you go on Amazon.com to order an e-product.

Banner image: A child at work collecting e-waste in the Agbogbloshie dump in Ghana. E-waste is fueling a global public health crisis. But the problem can’t be dealt with if nations fail to regulate e-waste, and if corporations continue embracing a profitable but highly destructive linear supply chain economic model, rather than a responsible circular economy model. Image courtesy of Fairphone via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Ever-smarter consumer electronics push world toward environmental brink

Citations:

Kalamaras, G., Kloukinioti, M., Antonopoulou, M., Ntaikou, I., Vlastos, D., Eleftherianos, A., & Dailianis, S. (2021). The potential risk of electronic waste disposal into aquatic media: The case of personal computer motherboards. Toxics, 9(7), 166. doi:10.3390/toxics9070166

Ferron, M. M., Kuno, R., Campos, A. E., Castro, F. J., & Gouveia, N. (2020). Cadmium, lead and mercury in the blood of workers from recycling sorting facilities in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(8). doi:10.1590/0102-311×00072119

Garcia-Vazquez, E., Geslin, V., Turrero, P., Rodriguez, N., Machado-Schiaffino, G., & Ardura, A. (2021). Oceanic karma? eco-ethical gaps in African EEE metal cycle may hit back through seafood contamination. Science of The Total Environment, 762, 143098. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143098

Igharo, O. G., Anetor, J. I., Osibanjo, O., Osadolor, H. B., Odazie, E. C., & Uche, Z. C. (2018). Endocrine disrupting metals lead to alteration in the gonadal hormone levels in Nigerian E-wastE workers. Universa Medicina, 37(1), 65-74. doi:10.18051/univmed.2018.v37.65-74

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.