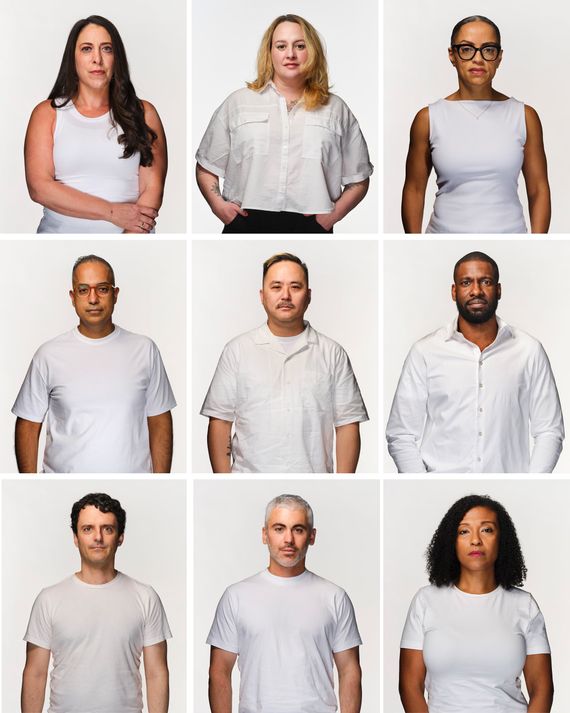

Forty-four 44-year-olds, including the author (top row, center).

Photo: Hannah Whitaker

This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

Doing karaoke is a great way to feel your exact age, something I only recently remembered. It was two days after Halloween, and my 44th birthday party at Lion’s Roar Karaoke House in Williamsburg was already in full swing. Younger attendees sang along with gusto to hits that were popular when they were in their 20s in the 2010s. During that decade, I was too occupied with reproduction and its consequences to pay much attention to the inexorable rise of Ariana Grande. Toward the end of the party, I performed “What’s Up,” by 4 Non Blondes, a song I’ve been karaokeing ever since its opening lines — “Twenty-five years and my life is still / trying to get up that great big hill of hope / for a destination” — were literally true. “Forty-four years and my life is still,” I sang that night. I spent the week after the party feeling hung-over, though I’m sober. When I looked at the photos of me at the mic, it was hard not to compare them to a slideshow my mother had sent me a few weeks earlier on my actual birthday. I’m pretty sure her collection had been automatically generated by Apple’s facial-recognition algorithm, but it still felt like an attack. In all of the pictures, some of which were taken with my mom’s first iPhone 14 years ago, I was so cute, so bright-eyed, so thin, so young.

Of course, I am still relatively young, at least compared to how old I hope to be in the future. And I’m often told that I don’t look my age, which is probably because of the way I dress (casual-disheveled) and how many tattoos I have, two of which are Gen-Z-coded stick-and-pokes rather than millennial-coded full color. But it’s also because the full impact of middle age hasn’t slapped me across the face yet. I might be deluding myself, but I feel like I still credibly blend in among my younger co-workers. The illusion isn’t punctured unless we start reminiscing about high school. Once, in a meeting, I mentioned that my school had put stricter security measures in place “after Columbine” and fleetingly saw the “Sure, Grandma, let’s get you to bed” meme flash across my colleagues’ faces. Mostly, over the past few years, I have felt like an old young person.

The feeling seems pretty common in my generation. We are in some senses younger than every middle-aged cohort before us. It’s been much more difficult for older millennials and cusp X-ers to attain the career status our parents had at our ages. Many live without a financial safety net, keeping us young in the “furniture from the street” way. We’re less likely to own homes or have emergency savings. When layoffs come around, both the high-powered boomers above us and the less-pricey Gen-Z kids on their way up are more likely to hang on to their jobs — at least until AI replaces the kids, then us.

It’s also possible, though expensive, for us to appear far younger than our parents did at our ages via Botox, fillers, and those red-light LED masks that make you look like a scary robot. We’ve all seen that photo of 70-year-old Kris Jenner looking 25; with enough money, we know we can opt out of many physical signs of our decrepitude. We might dress younger than our power-suited mothers did. Grown-ups are no longer identifiable via business-casual uniforms and staid haircuts; the pandemic has erased many offices’ taboo against wearing soft pants. If we want, we’re deluged with all the information in the world about what young people are wearing, listening to, reading, saying, and doing the moment we open our apps. We can swim in the same waters as them, and we often do without even thinking about it: TV shows based on YA novels or set in high schools are just as popular with 40-somethings as they are with viewers in the age bracket of the characters onscreen.

Add to all this: The world doesn’t really treat us like old people anymore. When we were kids, 40 was famously “over the hill.” To me, 40 felt more like another journalistic deadline I was blowing; there were lots of things I’d hoped to have achieved by that point in my life, but I would just have to ask the universe for an extension. I didn’t think about my body falling apart or my mortality as much as I mourned the loss of my identity as a precocious person. I’d spent my 20s being the youngest person in the meeting, an interloper in the world of established Gen-X-ers, racing to publish my first book before I turned 30. Then I spent my 30s recovering from and atoning for everything I’d said and done in service of my ambition, and reproducing. Soon after my 40th birthday, I got a full-time job for the first time in eight years and was suddenly a decade older than some of my bosses. No one accorded me the respect owed to an elder stateswoman; I was competing for the same opportunities as the 26-year-olds who shared my job description but not my extracurricular responsibilities, who were then 4 and 7 years old.

Regardless of how emotionally young or old I felt, I was heading for an aging milestone. While people were no longer rolling over the hill at 40, the new received wisdom said I’d soon be arriving at something more extreme: the cliff. The term entered the lexicon last year with Miranda July’s novel All Fours — which featured a diagram of the abrupt nosedive women’s hormones take sometime in our fourth decade — and the concept was expanded and reinforced by the publication that August of a widely discussed “nonlinear aging” study from Stanford. That research seemed to confirm something we already sort of knew: There are certain years in life when aging hits us hard and moves us forward at hyperspeed. Forty-four, according to the study, is the first of those years. Sixty is the next, and there may yet be more cliffs to be discovered. The Stanford scientists found these transition points by examining the markers of cellular aging in roughly 100 people between the ages of 25 and 75. Over the course of the study’s 12-year duration, they discovered these markers became increasingly dysregulated in bursts around certain ages. At first, they were skeptical that 44 was a true aberration, thinking that perimenopausal symptoms must be skewing their results. But when they broke the data out by sex, they found that men were experiencing the same key changes women were: increased risk of cardiovascular disease and reduced ability to metabolize fat, alcohol, and caffeine.

I first read the study about six months before my 44th birthday. Mostly, it made me feel guilty and scared. At 43, I wasn’t exactly being proactive about my physical health. Some of the factors were out of my control — or at least they felt that way. I was on a cocktail of medications for bipolar disorder that all had sedative effects; no matter how much coffee I drank, I couldn’t seem to muster the energy to do something as ambitious as “going to the gym.” Besides, I had no time: I spent every waking hour either taking care of my kids or working, the exception being a brief period between 9:30 and 11 p.m. that I spent watching TV with my husband in a semi-prone position on the couch. Caffeine was my god. Nicotine, I’m ashamed to admit, was also my god in the form of Juul pods. Cutting out refined sugar seemed like the first step toward a Goop-ian nightmare with orthorexia at its inevitable end point. GLP-1’s were for rich people. My lifestyle wasn’t exactly a point of pride, but I didn’t see how I could be expected to do much better. Between constant deadlines and family stressors, my central nervous system was in a perpetual state of near collapse. My periods had been weird for several years. And underneath it all was low-level dread that this was just the beginning of my irreversible decline. Whether I fell off the cliff or not, I’d still be lucky to reach 88. I was in the second half.

Photo: Hannah Whitaker

Aging is widely understood in our culture as a problem to be solved, not a natural and inescapable bodily process. The media coverage of the Stanford study was no different. Much of it suggested that the cliff might be preventable or at least could be delayed. But the potential remedies offered were cold comfort: They were the commonsensical things doctors always recommend — get enough sleep, reduce stress, exercise moderately with an emphasis on strength training, stop eating refined sugar and processed food. Boring! Also: Impossible?

I wondered what the study’s researchers thought of this, and I also didn’t feel totally confident that I’d comprehended the paper — which includes sentences like “Phosphatidylinositols are a class of phospholipids that have various roles in cytoskeleton organization” — so I called Dr. Michael Snyder, its senior author. Answering the phone, he told me I’d caught him just as he’d finished his morning exercise routine, which includes both cardio and strength training. The study is ongoing, and Snyder is himself a formal participant, getting his own samples analyzed along with the others. He told me he doesn’t believe that the aging cliffs are an immutable fact of biology. The changes he and his team documented, he said, are a representation of what currently is, not what might potentially be. If people go into their late 30s and 40s with the understanding that their bodies are going to distinctly change — that they’re not going to be able to get by merely doing what they’ve always done — then they have a chance to improve their outcomes. So far, the study has not provided any meaningful conclusions about whether this is the case.

Snyder’s take fits comfortably with the orthodoxy of our time: that our health is adaptable, that everything is possible if we look, if we research, if we try. But the reality of aging is evident all around us. In the months before I turned 44, I talked to quite a few people who had already crossed that threshold, the first drop. They talked about injuries and illnesses and some bodily changes that had never even crossed my mind. Multiple people mentioned plantar fasciitis, inflammation of the band of tissue on the sole of the foot. My days walking around barefoot, which I’d been taking completely for granted, were apparently numbered. “My feet just stopped working last year,” said Samantha Tunis, 45. “I took a dance class and felt great during, and then the next day I couldn’t put any weight on my right foot.” Sufferers can experience pain so extreme that they have difficulty standing and walking, and there’s no quick fix. The same thing happened to Jana when she was 43; her condition was so bad that she needed physical therapy and oral steroids — and this was during the pandemic, when she was walking everywhere with her stroller-age son.

I also heard from people who, at 44, had perfect vision one day and needed glasses the next. People who went from drinking three or four cocktails on a Thursday and waking up refreshed to being unable to tolerate more than a glass of wine without feeling hung-over for days. Women who felt like their skin texture had changed overnight, becoming saggy and crêpey instead of firm and taut. Several told me that they’d become basically unable to lose weight around 44, and some had turned to GLP-1’s.

The most dramatic story of sudden change was Allison Wright’s. At 43, she learned that she would need a double hip replacement. She’d previously been incredibly physically active: She loved spin, hot yoga, and Pilates, which she mixed with some weight training. But at 42, she noticed pains on the right side of her body, concentrated around her hip.

An initial MRI diagnosed her with gluteal tendinosis, a glute tear, a hamstring tear, and a labral tear, all on the left. She also learned she had previously undiagnosed congenital hip dysplasia. The first orthopedic surgeon she talked to told her that, while her hips did need to be replaced, she was too young for the surgery — she would just need to replace them again in 20 years or so, when she’d be older and more susceptible to complications. Wright resolved to look for a surgeon who would give her the relief she needed as soon as possible.

Now 46, Wright’s daily life is full of minor indignities. Doctors have told her not to engage in any physical activity more strenuous than walking, and even then, she’s not supposed to walk on “uneven surfaces,” a constant challenge in hilly Charlottesville, Virginia, where she lives. On a recent vacation, she found she needed the help of a cane to navigate the sand at the beach. She has to bring a padded cushion into restaurants because of the damage to her glutes. Her physical struggles have affected every aspect of her life, including her sex life and her relationship with her family.

“I feel like I’m losing some of the best years of my life to pain and immobility,” she told me. In April, she underwent a surgery to shave off the top of her left femur, which has mitigated some of her pain without requiring a full hip replacement. Still, she is deeply bothered that there isn’t a clear explanation for what happened to her. “All the doctors, all the physical therapists, they always ask, ‘Was it an impact injury? How did this happen?’ And I can’t point to anything. I was very active, working with trainers. My body just started to fall apart.”

Wright’s health collapse may be extreme, but the lesson seems to hold, even if you manage to make it past 44 relatively unscathed: You can run all you want, but you’re still running toward the cliff.

Photo: Hannah Whitaker

With only a few months to go until my 44th birthday and not much wiggle room in my schedule or budget, I decided to look into my options.

I called a well-known gynecologist, Dr. Elizabeth Poynor, to get her read on how gender fits into nonlinear aging and also to sneakily get her permission to seek out hormone-replacement therapy. I’d been hearing and reading that it was beginning to be prescribed to women who are, like me, in the early stages of perimenopause (the eight-to-ten years before your periods stop completely, as you know if you’ve read any of the 10 million articles or novels recently published on the subject). Poynor has written extensively on the need to separate obstetrics and gynecology to allow doctors to focus on women who’ve aged out of the concerns endemic to the reproductive years. She has also treated Martha Stewart. I was very eager to hear her take.

When she first read the Stanford study, Poynor told me, she was unsurprised that the changes it reported would be seen in women around 44 — it was somewhat intuitive given their fluctuating hormones and declining ovarian reserve. She’s an advocate for starting hormone-replacement therapy earlier rather than later. “We know that starting estrogen is associated with a lower level of insulin resistance,” she said. “So it does help to support metabolism.” Like Snyder, she detailed how important sleep, stress reduction, and regular exercise are, but I was more focused on finding a magic pill I could start taking. When July’s All Fours heroine starts smearing progesterone cream on her thigh, it changes her life and her body, helping her transform from a thwarted artist in a settled-down hetero marriage into a horny gym rat who videotapes herself performing elaborate dance routines and only dates non-men. My own ambitions were more modest, but I still wanted to see what hormone therapy could do for me.

My psychiatrist gave me a recommendation for a gynecologist who specialized in perimenopause and didn’t take my insurance. The initial appointment was $1,200, but it was also an hour long, including 45 minutes of chitchat about my medical history that delved into areas like my astrological chart and my relationship to my mother. The gynecologist, by that point my new spiritual guru, did bloodwork and found that both my estrogen and my progesterone could stand to be topped up. After some trial and error — including a low-dose birth-control pill with synthetic progesterone that made me immediately depressed — I settled into a regime of bioidentical estrogen patches, applied weekly four times a month, and bioidentical progesterone, taken during the last two weeks of my cycle. A few months into the new system, my cycles were exactly 28 days long for the first time in four years, and I no longer spent days 14 to 22 convinced that all my friends hated me and my life’s ambitions were doomed.

My appearance was going to be harder to hack. Out of the gate, I had a big advantage (knock wood): I have naturally plump cheeks and a smooth forehead, the genetic inheritance of my father and his mother, who both looked about 40 well into their 60s. I’ve never been tempted to try Botox. From the neck down, it’s a different story. I’d spent most of my adult life as a medium-thin person, thanks to a speedy metabolism and a freelance/intermittently employed writer’s schedule that left plenty of time for exercise. Then, with my first pregnancy, I experienced diastasis recti, where the midline of your abdominal muscles basically unzips (disgusting). Even though I did extensive physical therapy to get my abs to reunite, they never quite got all the way back together and then I got pregnant again. I have long arms and legs proportionate to my torso, and the bulge in my midsection has gotten me seats on the subway for years. I’ve tried not to let it bother me. But this became more difficult after I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed antipsychotics in 2022. I gained an intractable 30 pounds almost instantaneously after going on the drugs, even though nothing about my diet had changed.

For years, I have attempted to hypnotize myself into body positivity, or at least body neutrality, even as I’ve had to buy increasingly larger clothes. I subscribe to newsletters about the harmful effects of diet culture and the misogyny of big pharma, and I believe wholeheartedly that health is possible at any weight. And yet. When my new gynecologist asked me, in an offhand way, how I would feel about losing 30 pounds, somehow the first words that came out of my mouth emerged directly from my hindbrain: “It would feel like getting an extra $30,000 in my paycheck.” She didn’t hesitate to prescribe me Mounjaro. I didn’t meet my insurance’s criteria for GLP-1 coverage — my A1C, a measure of average blood-sugar levels, firmly indicated that I wasn’t prediabetic in the slightest, and my BMI didn’t qualify me as obese. But I decided I was willing to pay out of pocket, within reason. My gynecologist sent the prescription to a Canadian pharmacy so I could get the drug for around half its American cost.

My honest review of Mounjaro is that it put me in a really weird headspace. Typically, I love food, even mediocre food; being hungry and then being satisfied is one of the very few small, reliable pleasures in my life. So the first few days of simply not feeling hungry at all, ever, were a mindfuck. I still ate because I understood, intellectually, that my body required sustenance. I came around on the appeal of things like smoothies and açai bowls — nonfoods you could consume without much effort or conscious thought at a desk or while scrolling through your phone. Mounjaro also made me so constipated that I resorted at one point to a message-board-recommended Israeli laxative that had roughly the same effect as colonoscopy-prep solution.

After tariffs kicked in, importing Mounjaro from Canada became almost as expensive as paying full price, and in three months of taking 2.5 milligrams a week, I’d lost only three pounds. Overall, I would give the drug two out of five stars, and those stars are simply because the glimmer of hope associated with the decision to try it compelled me to join the Y and start swimming again and to go to one medium-intensity yoga class a week.

I didn’t change my caffeine intake one iota. I quit vaping and started chewing nicotine gum and smoking the occasional cigarette instead, reasoning that cigarettes’ finite and meditative aspects were preferable to ingesting a near-constant stream of chemical vapor. We could generously call this a harm-reduction approach. I talked to my psychiatrist and began to taper down gradually on the most sedating of my various sedatives. Like all body-optimization projects, this is a work-in-progress.

Photo: Hannah Whitaker

Would it be healthier to accept our certain decay and mortality than rage against the dying of the light (or dewy glow), throwing as much time and money as possible into anti-aging measures? Where is the line between a wholesome level of self-care and an obsessive, Pyrrhic war against an indomitable enemy? Consumer culture shouts at us constantly that we can always be doing more: We can hack our bodies, gathering data to improve almost everything about ourselves. But we’re also told that acceptance is the path toward peace and contentment. I thought about the older women I know, the ones well past middle age who seemed to have found a way to avoid being made insane by these contradictions. How had they become truly “older and wiser”?

I became friendly with Kim France, age 61, a couple years ago, when she and author Jennifer Romolini had me as a guest on their podcast, Everything Is Fine, which is itself about navigating the second half of life. Once upon a time, France was a staff writer at now-legendary Sassy magazine. From there on, she had a thriving career in journalism — one that nearly took her out. She has written with skill and clarity about the soul-killing depression that she experienced at her professional pinnacle at Lucky magazine, which she founded in 2000. In 2005, overworked, she had a manic episode that landed her in a psych unit. Though our lives don’t line up perfectly — France is partnered but happily child-free, and I’ve never had a Condé Nast car and driver or owned a townhouse — I’ve always felt I have a lot to learn from her example, particularly the way she’s reinvented herself throughout the decades while still coping with the inevitable ups and downs of life with chronic mental illness.

France wanted to reassure me that life is better for her now than it was in her 40s or even her 50s. Part of the reason, she said, is that she no longer feels “like an old person trying to be young.” She’d crossed over, she said, to being “a young old person. I’m in the freshman class.” More profoundly, she told me, a great equalizing has taken place: Most of her contemporaries have experienced life’s harshest realities. “If you get to be my age,” she said, “pretty much everyone has kind of walked through the fiery valley at least once. Something terrible has happened to them, something traumatic, something they had to get over. And when you’re 44, that’s not true. There’s something to being an age where you’ve come out the other end of all the drama that gets stirred up in your 40s.” I thought about the connection I feel now with friends who’ve had their lives upended; I hadn’t considered it in those terms before. With friends who’ve been lucky enough to have avoided a major loss, a divorce, a brush with death, or any other “life before” and “life after” catastrophe, I keep the conversation light, the same way my friends who experienced tragedy before me used to do with me. That we would all one day be on the level, as France described it, was perversely reassuring. Even if it were possible to stay young and carefree forever, it would mean missing out on the kind of spiritual growth that comes only from passing through pain.

While I see France as sort of an idealized older version of myself, I’ve never been delusional enough to even aspire to be like Genevieve “Genny” Kapuler, who should be pictured under older and wiser in the dictionary. I met her in my 20s, when I spent a lot of time doing alignment-based Iyengar yoga, the best kind for people, like me, who have scoliosis. When I got a six-figure book deal at 28, the first thing I did was enroll in yoga-teacher training (grad school for the especially feckless). I was fascinated by Kapuler, who is now in her late 70s and still guiding several classes a week. She has always seemed like the happiest, most youthful-spirited older person I’ve ever met. At an age when most people who do physical work are retired, she’s still bounding around the room with the energy of a teenager. During her classes, held in her enormous Soho loft (thrilling), she would adjust my postures with a gentle touch that felt like magic.

Kapuler has never been terribly concerned with her aging body. “I would say physically my joints are stiffer. There’s a lot of poses I can’t do,” she told me. “I don’t do drop backs anymore.” (She means backbends that start from a standing position and end with one’s hands on the floor, spine arched into full wheel pose.) “I don’t want to hurt myself.” But in terms of her “perception,” she said, “that which I love, that which I find beautiful, that which gives me more inspiration — that gets stronger every day.” Kapuler also doesn’t romanticize youth. “I didn’t feel that being young was so easy,” she said. Her 30s and 40s were full of joy — the birth of her son, her beginnings as a teacher — but also full of sadness with the deaths of her parents and the ineludible challenges of raising a child. On the whole, she’s much more at peace now that she’s older. “I’m not being Pollyanna about it,” she said. “I accept how complex and difficult it is to be a human being in this world. But on the other hand, if I stay focused on that which I feel is worthy of my attention, I am content.” Talking to her makes me feel as though, if I focus on the aspects of life that I love, the way she does, I have a chance at the enlightenment she radiates.

Joyce Maynard, the 72-year-old memoirist and novelist, is another older person who has continued to work steadily, teaching and writing and publishing books. Despite, or maybe as a reaction to, a difficult childhood and the mixed impact of early fame, she’s a constitutional optimist. She’s also preternaturally vigorous and energetic, which she chalks up to good luck and good genes. When we spoke recently, she was about to take a cross-country camping trip with her boyfriend. “I’ll name my energy as a crucial aspect of what has gotten me through difficult things in life,” she said. “But that said, I also hugely believe it has to do with one’s attitude and approach. And I’ve witnessed this in countless women.” She runs a memoir-writing retreat workshop for women in Central America, which keeps her in touch with younger people, and she said she’s continually learning new things. “I’ve had the great privilege of hearing and helping to shape many, many women’s stories, often stories that were very private and personal to them. It’s definitely expanded my understanding of the world and all the different things that happen in people’s lives.” In her later career, she’s experienced a newfound sense of freedom. When she was my age, she told me, “I gave myself over to my children. I did my career with whatever was left of me after taking care of everybody else, which I think was a story for a lot of women.” Now that her children are well launched into the world, she’s focusing on teaching and writing with a new vitality.

Approaching the second half of life this way is a choice, Maynard said. “You can either be left in the dust looking around, or you say, Well, now who am I? What do I want?” She said she knew her vigor couldn’t last forever. “Obviously, something’s going to get me, but until it does I’m going to keep going.”

For Kim, Genny, and Joyce, 44 was the beginning of an exciting, albeit exacting, new phase of life. Staying young is in some part a matter of appreciating the opportunity to get old. It also requires being grateful for what you have while you have it — however limited it might seem compared to the past. If I’m lucky, I’ll look back on 44 and reminisce about how youthful I was then; how much fun it was to lead a rough-and-tumble life with my husband and our two irrepressible kids, how I could still get hit on by bodega guys if I wore heels and eyeliner. But I have plenty to look forward to (besides plantar fasciitis). “Forty-four years and my life is still / trying to get up that great big hill of hope,” I sang at my party. Maybe the ground is about to drop, but I’m setting my sights on singing “88 years and my life is still …”

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the December 1, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the December 1, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York

The one story you shouldn’t miss today, selected by New York’s editors.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice