“It was concerning for me,” she said. “I’d always been regular, never on birth control.”

Her gynaecologist suggested Sedoric’s running and workouts – and stress – were the culprits. But that didn’t make sense: Sedoric had been a three-varsity-sport athlete in high school and continued working out with her college sports teams, so she hadn’t been exercising any more than usual. The doctor ordered a blood test, which showed slightly low oestrogen levels. She was prescribed progestin, a form of the hormone progesterone, for a week to reset her menstrual cycle. When that failed, the doctor said it might take some time and to “come back in a few months”.

But a few months later, still without her period, Sedoric began experiencing severe hip pain.

Odd, disparate symptoms continued to accrue, including pelvic floor pain, for which she received a series of nerve-blocker injections through her vagina, and leg pain, which required physical therapy. The jaw pain never stopped. A new oral surgeon suggested “breaking my jaw and putting it back in place”, she said.

Then, after moving from her parents’ home in New Hampshire to an apartment in Lower Manhattan, Sedoric noticed subtle changes in her body: her face seemed to be broadening, her lips got puffier and her fingers swelled to the point that the cherished gold ring belonging to her grandmother that she always wore snapped. “My body was deforming before my eyes,” she said. She attributed the shifts to routine ageing, living in New York City, drinking with friends and the ongoing stress of the pandemic.

After two years, several misdiagnoses and some painful treatments that didn’t help, Sedoric was about to give up on solving her health problems. Then, in desperation, she decided to seek help at a private medical clinic, which, for a hefty fee, conducted an exhaustive battery of tests. What emerged from those tests eventually put her on the path to figuring out that she had a rare, life-altering condition that would undermine her sense of self in profound ways.

“I lived in pain and was gaslit for years,” Sedoric said. “But the experience gave me a different perspective, like you almost died, but now you get to live.”

Desperate for answers

In 2021, during a Christmas holiday in New Hampshire, Sedoric said her best friend’s father, an orthopaedic surgeon, recommended a privately run clinic in Colorado that conducts comprehensive testing and full physical work-ups for people with difficult-to-diagnose conditions. The catch: a price tag that would ultimately top US$21,000 ($36,361) – no insurance accepted. Sedoric’s parents agreed to pay and in February 2022, she flew to the Resilience Code headquarters in Englewood, Colorado, for four days of testing.

She met with neurosurgeon Chad J. Prusmack, the company’s founder and CEO, for about 90 minutes to review her medical history. Then she spent the following days undergoing tests. She had an MRI of her brain and a biomarker panel looking at thousands of conditions. Blood work tested her for a variety of potential problems, including viral and gut conditions, as well as inflammatory, immune and hormone imbalances.

“When you get a whole bunch of labs, it tells a story of the patient,” Prusmack said. “It doesn’t take a snapshot and leave out some of the important details.”

Before the results came in, she said, Prusmack told her he predicted she had Lyme disease, and then prescribed several medications to treat her symptoms. None of the pain medicines worked, she said.

“Except for the ketamine: for 30 minutes I was in no pain, but I couldn’t function, so it wasn’t really a long-term solution.”

One month later, on a Zoom call with Prusmack, she got the news: it wasn’t Lyme disease. It was, most likely, a condition related to the substantially elevated level of IGF-1, a marker for growth hormone, picked up on a test Sedoric had not previously been given. The upper limit of IGF-1 for a person Sedoric’s age was about 200, Prusmack said, but hers was 523, which suggested an endocrine-related problem.

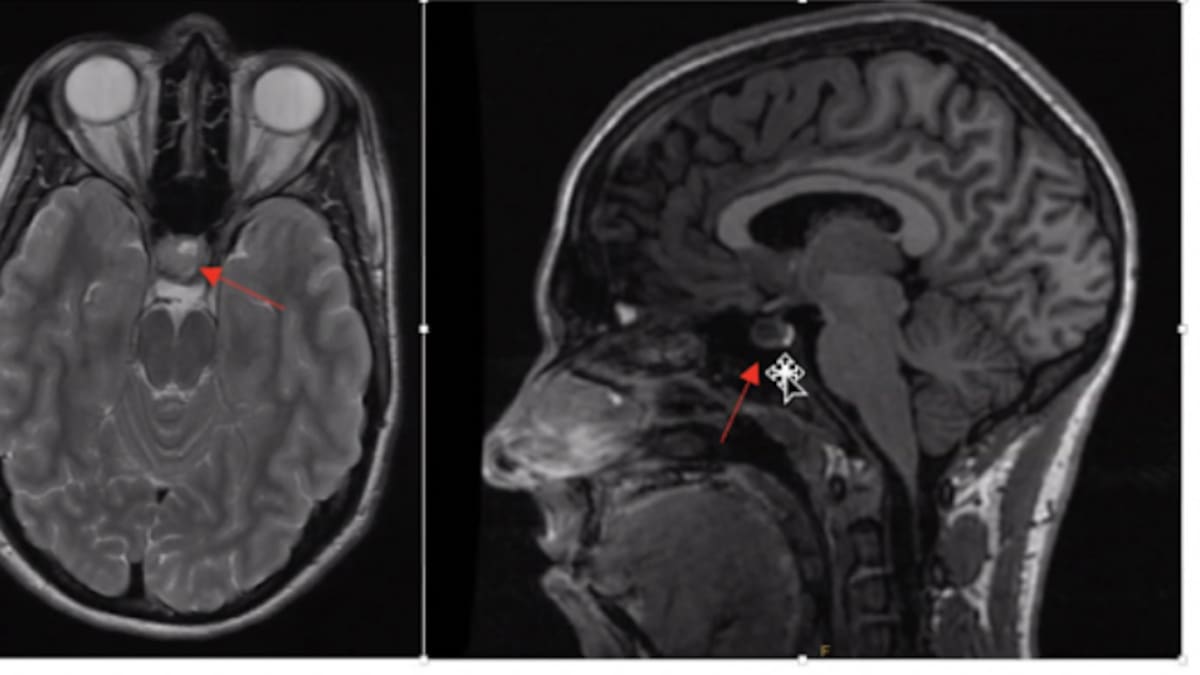

The MRI also showed a tumour on Sedoric’s pituitary gland, a pea-size structure that sits at the base of the brain and is often called the “master gland” because it releases hormones responsible for many critical functions, including growth, metabolism, sex and reproduction, and the body’s response to stress.

The news stunned her. She said it was a relief to pinpoint the problem, but “not in my wildest dreams did I think I had a brain tumour and I had no idea how bad it was”. Sedoric texted her roommates, and together they ran through the streets of the Lower East Side, screaming and crying.

The next day, she started interviewing surgeons.

Sedoric secured an appointment with Tim Smith, a neurosurgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Smith said a follow-up MRI showed Sedoric’s tumour was a 1.4cm “macroadenoma”. Doctors also finally gave her an official diagnosis that explained her years of frustration and pain. She had acromegaly, a rare condition that, in adults, causes certain bones, organs and other soft tissue in the face, jaw, hands and feet to grow far beyond what is typical. In children, whose growth plates have not yet closed, the condition can cause excessive height and is known as “gigantism”. Among the most famous people with gigantism was Andre the Giant.

Smith said Sedoric did not appear with many of the telltale signs of acromegaly, which afflicts about 30 to as many as 120 people out of a million, according to various analyses that show prevalence to be higher than previously thought. She didn’t have an obviously prominent jaw, for example, or a massively larger shoe size. Still, her arthritis-like joint pain was unusual for a fit, young adult, he said.

“At her age and with her athleticism, this [collection of symptoms] was just very strange,” Smith said.

She did display some classic symptoms, he said, including swelling in her face and hands and what’s known as frontal bossing, a prominent or bulging forehead.

This happened, Smith said, because the excessive growth hormone secreted by the pituitary caused overgrowth of cartilage, bone and a form of connective tissue called synovium, which first made the joints look bigger and then caused them to stop working normally.

On April 26, Smith successfully removed Sedoric’s tumour. About an hour after the operation, however, she said she got out of bed to use the toilet and suddenly felt nauseated and off balance. The next thing she remembers is waking up covered in vomit with about a dozen medical professionals staring at her.

She had apparently thrown up and breathed it in through her nose, causing the vomit to travel up through the surgical cavity. Soon, she was in the intensive care unit with a high fever and throwing up blood; a spinal tap confirmed she had bacterial meningitis. Bacteria from her gut had infected her brain and spinal fluid; doctors performed a second surgery to clear out the infected area.

Sedoric returned home after two weeks.

Living with uncertainty

It hasn’t been an easy recovery. She has less jaw pain and the swelling and puffiness in her body transitioned back to normal. But she’s developed headaches, still has pain in her legs and suffers lingering trauma from the surgery complications.

Her future remains uncertain. An analysis of Sedoric’s tumour found she has a more aggressive form of the disease; there was a 20-40% risk of a recurrence within 10 years, Smith said, and a lifetime risk “close to 100 per cent”.

Sedoric sees endocrinologist Nidhi Agrawal, the director of pituitary disease at the Holman Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at NYU Langone Health, every six months to closely monitor her symptoms.

Agrawal says in certain ways, Sedoric is lucky. While some of the bone growth she experienced is irreversible, much of the soft tissue expansion has resolved because her acromegaly was diagnosed only a couple of years after symptoms began. The typical diagnostic delay for acromegaly was generally five or six years, Agrawal said, which is an improvement from a few years ago when the delay was closer to 15 years.

“These are patients who have been just hopping around seeing different practitioners and just not getting the diagnosis,” she said.

Agrawal says she now tries to educate medical students, dentist groups and other specialists to let them know that if patients come in complaining of unexplained pain in disparate body parts, it could be acromegaly.

Sedoric, now 28, has tried to integrate her illness into daily life. She remains active – she ran the New York and Chicago marathons recently and plans on completing the Boston Marathon in April – and enjoys her job as a sustainability consultant. She is not taking medication for her condition.

From the outside, her life looks fairly typical.

“I hang with friends, run marathons, look pretty normal,” she said. “But it’s hard when you have an invisible disease with no cure that comes with constant pain and could deform your body at any time.”

She is learning to live with uncertainty.

“The most difficult thing is trusting myself,” Sedoric said. “Like having to look in the mirror and decide if I have a swollen face because I didn’t get enough sleep or if I have a tumour. It’s trusting when to take it seriously and when to let go.”