With vague symptoms and no screening test, ovarian cancer can be deadly. According to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, 20,890 people will receive an ovarian cancer diagnosis in 2025 and of these, more than half will learn that their ovarian cancer has spread to distant organs.

But Hua-Ying Fan, PhD, a professor in The University Of New Mexico’s School of Medicine, Division of Molecular Medicine, hopes that her latest discovery may increase the number of people who survive. Fan, who is also a member of the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Cellular and Molecular Oncology research program, published a study in Cancer Research Communications in October.

According to the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, chemotherapy treatment for ovarian cancer often starts with carboplatin, cisplatin and paclitaxel, which kill fast-growing cells. Fan says that although more than 80% of people with advanced ovarian cancer respond to this treatment, only half of them will live longer than 18 months because the cancer often returns.

“Most ovarian cancers that recur eventually become platinum-resistant,” Fan says. “Treatment options are limited once ovarian cancer becomes resistant to platinum-based chemotherapy.”

In 2017, Fan started looking for ways to help patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Using results from previous work, she focused on a series of cellular chemical reactions called the Notch pathway. She found that certain ovarian cancer cells, called OVCAR3 cells, do not respond to the platinum-based chemotherapy drug cisplatin, and they depend on the Notch pathway for their survival much more than non-cancerous cells do.

Fan’s work led her to show that a drug called auranofin, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already approved for rheumatoid arthritis, can disrupt the Notch pathway. The work was published in October in the article, “Auranofin Synergizes with Cisplatin in Reducing Tumor Burden of NOTCH-Dependent Ovarian Cancer.”

The article describes several experiments that Fan and her team conducted on OVCAR3 cells. In one experiment, Fan and her team of scientists treated OVCAR3 cells with auranofin and cisplatin. Many of the OVCAR3 cells died.

In other experiments, Fan used organoids and aminal models to further study the effects of this drug combination. For these experiments, Fan sought the help of two other colleagues at UNM: Mara Steinkamp, PhD, an associate professor in the UNM Department of pathology and the faculty director of the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center Animal Models Shared Resources; and Kimberly Leslie, MD, research professor in the UNM Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Molecular Medicine and member of the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center Therapeutics research program.

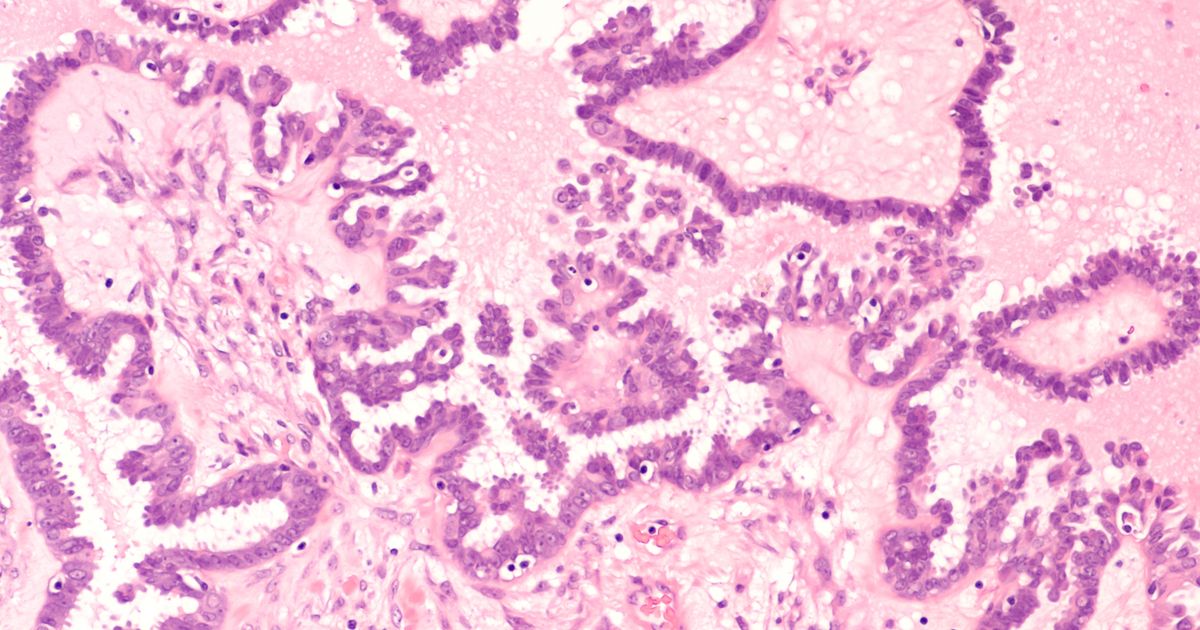

In an additional experiment, the team used cells taken from patients with ovarian cancer and grew organoids, which are three-dimensional clusters of cells that can be used as a model of that patient’s cancer. They then treated the organoids with auranofin and cisplatin. They found the higher the amount of the drug combination given to the organoid, the more ovarian cancer cells died.

In another experiment, the team used small animals with ovarian tumors to study the effect of their drug combination. The animals that received greater amounts of the drugs lived longer and had smaller tumors.

“This study reflects broad collaboration across clinical, translational and basic science teams at UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center,” Fan says.

But she cautions that more studies are needed before the drug combination can be given to people with advanced ovarian cancer. And because of the variation among ovarian cancer patients, not every patient may benefit from this discovery, she says.

Still, Fan has hope that future studies will show a potential benefit for many people. For them, making their treatment a notch more effective may enable them to live beyond the median 18 months.

Paper Reference

“Auranofin Synergizes with Cisplatin in Reducing Tumor Burden of NOTCH-Dependent Ovarian Cancer” was published online on October 10, 2025, in Cancer Research Communications.

The authors are: Robert J. Lake, Parisa Nikeghbal, Irina V. Lagutina, Kimberly K. Leslie, Mara P. Steinkamp, Hua-Ying Fan. The article may be found online here.

The University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center

The University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center is the Official Cancer Center of New Mexico and the only National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center in a 500-mile radius. Its 136 board-certified oncology specialty physicians include cancer surgeons in every specialty (abdominal, thoracic, bone and soft tissue, neurosurgery, genitourinary, gynecology, and head and neck cancers), adult and pediatric hematologists/medical oncologists, gynecologic oncologists, and radiation oncologists. They, along with more than 600 other cancer healthcare professionals (nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, navigators, psychologists and social workers), provide treatment to 65% of New Mexico’s cancer patients from all across the state. And they partner with community health systems statewide to provide cancer care closer to home. In 2024 they treated more than 15,000 patients in almost 105,000 ambulatory clinic visits in addition to in-patient hospitalizations at UNM Hospital. A total of 2,075 patients participated in cancer clinical trials to study new cancer treatments that include tests of novel cancer prevention strategies and cancer genome sequencing. The more than 123 cancer research scientists affiliated with the UNM Cancer Center were awarded $38.3 million in federal and private grants and contracts for cancer research projects.

Website: unmhealth.org/cancer

UNM Cancer Center Clinic: 505-272-4946