I. Artemis, We Have a Problem

As you may have heard, NASA plans to send a crew of astronauts around the moon in early 2026, followed by a lunar landing in 2027. Or maybe you haven’t heard. When I told one of my daughters about this plan to send people to the moon, she said, after a long silence: “But I thought we already sent a bunch of people there a long time ago.”

This is a standard response when I quiz people about Artemis, NASA’s program to return to the moon, and this time to stay. It’s named for Apollo’s twin sister and the goddess of the moon and the hunt. You can ask even the most news-savvy people for their opinion on Artemis and be answered with blank stares. The other day, I was in a gaggle with six neighbors, all highly informed professional people—two of them with long careers at the National Science Foundation—and none knew anything about Artemis except one thing: It’s a plan to send people to Mars.

Nope. Artemis is a moon mission. There is no Mars mission. NASA has no Mars rocket, no Mars capsule, no Mars mission crew. NASA has Mars aspirations, but it doesn’t even have a timetable for such a venture.

What it does have is a very troubled moon program. Artemis faces fundamental engineering challenges that have called into question the program’s basic architecture. Reconfiguring a mission this important is hard in the best of times, but the agency is being forced to do it during a year of unprecedented internal turmoil.

A new administration always means turnover, but NASA has been in an uncontrolled spin every bit as alarming as the one Neil Armstrong famously pulled out of during Gemini 8 in 1966. More than a year ago, President-elect Donald Trump nominated a billionaire entrepreneur and Elon Musk ally, Jared Isaacman, to become NASA administrator. It was an unconventional choice, but Isaacman drew support from many quarters in the space community. Then, right before Isaacman was poised for confirmation by the Senate, Trump and Musk had a nasty falling-out, and Trump yanked Isaacman’s nomination.

Since Inauguration Day, NASA had been run by acting administrator Janet Petro, a veteran agency official, and with Isaacman out, she remained in charge until one day in July when Trump suddenly named Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy as interim administrator. Duffy, a former congressman and reality TV star, has no aerospace background. He has also continued to run the sprawling Transportation Department.

Then on Nov. 4, Trump announced he was renominating Isaacman.

Isaacman is expected to be confirmed by the Senate soon, but as I write this on a chilly morning in early December exactly one year to the day after his original nomination, Isaacman still is waiting to take charge. NASA, which is one of the only federal agencies both Democrats and Republicans consistently agree they like, hasn’t been spared the tumult of Trump’s return to power. And as with the administration’s attempted “deconstruction” of so many agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, NASA officials were ordered to produce, on a tight deadline, justifications of thousands of previously approved contracts. In an agency where “budget is mission-critical,” the president’s fiscal year 2026 budget request to Congress was a gut punch, demanding a 24 percent cut in the agency’s overall spending. Much of that would come by cutting nearly half of NASA’s science budget. Such a budget would kill dozens of robotic missions, including fully operational probes for Mars, the moon, Jupiter, and the outer solar system, as well as future missions to explore Venus.

Congress has the power of the purse, but the possibility of massive cuts has led to a disastrous talent drain. NASA, like other agencies, was also hit early this year by a rash of White House demands and executive orders that made life difficult for its employees. No remote work. Travel halted. Advisory groups disbanded. Subscriptions to prestigious scientific journals killed amid spurious claims that the journals publish “junk science.” By August, more than 4,000 NASA civil servants, nearly a quarter of the workforce, had left the agency through buyouts, early retirement, and layoffs.

A senior NASA official I talked to over the summer put it this way: “It’s like we’re tossing the crown jewels in the Thames.”

As Trump continues to roil the federal government, comparatively little attention has been paid to the $25 billion agency that has rightfully been a source of national pride since the first American astronauts rode rockets into space. It has produced astonishing discoveries about our solar system and our universe. Its ambitions have lured brilliant minds to our country and funneled research dollars to our universities. It has spurred technological innovations that are embedded in modern life.

I’ve written about NASA periodically for four decades, with a particular interest in space science. I admire the agency and its dedicated workforce. It’s distressing to see it struggle. NASA matters to America, and—if you’ll forgive me for getting lofty—it matters to the future of humanity, and to all the other living things that inhabit our planet.

There’s more going on than just a space race to the lunar south pole. We’re in a new phase of the Space Age. What happens in the coming decades may tell us much about human destiny—and whether it really lies, as many of us long believed, in the stars.

II. The New Space Race

It’s understandable why some people think Artemis is a Mars mission: NASA rarely talks about Artemis without saying something about Mars in the same breath. It’s supposed to be a package deal: “Moon to Mars.” That’s the phrase.

Going to the moon instead of straight to Mars is actually quite sensible. Mars—contrary to what you might have heard—is not yet a plausible human spaceflight target for a government-run program that’s not supposed to kill its astronauts (who, by the way, are federal employees). Mars is a nasty place. It’s a cold, dusty, desert world, nearly airless. The planet’s trifling atmosphere—about 1 percent the density of our own—is notoriously too thin to help slow down a spacecraft attempting to land, but can still create turbulence and potential disaster. And under any plausible scenario with current propulsion technology, a one-way trip to Mars would take at least six months. Due to orbital dynamics, a round-trip mission would take more than two years.

Before the agency even attempts to send people to Mars, it wants to “buy down risk,” the financial term frequently used at NASA, by testing capabilities and procedures for long-duration, off-planet missions. There’s a ton of risk to buy down. But, the thinking went, there is a perfect proving ground conveniently circling the Earth, never more than about three days’ travel time away.

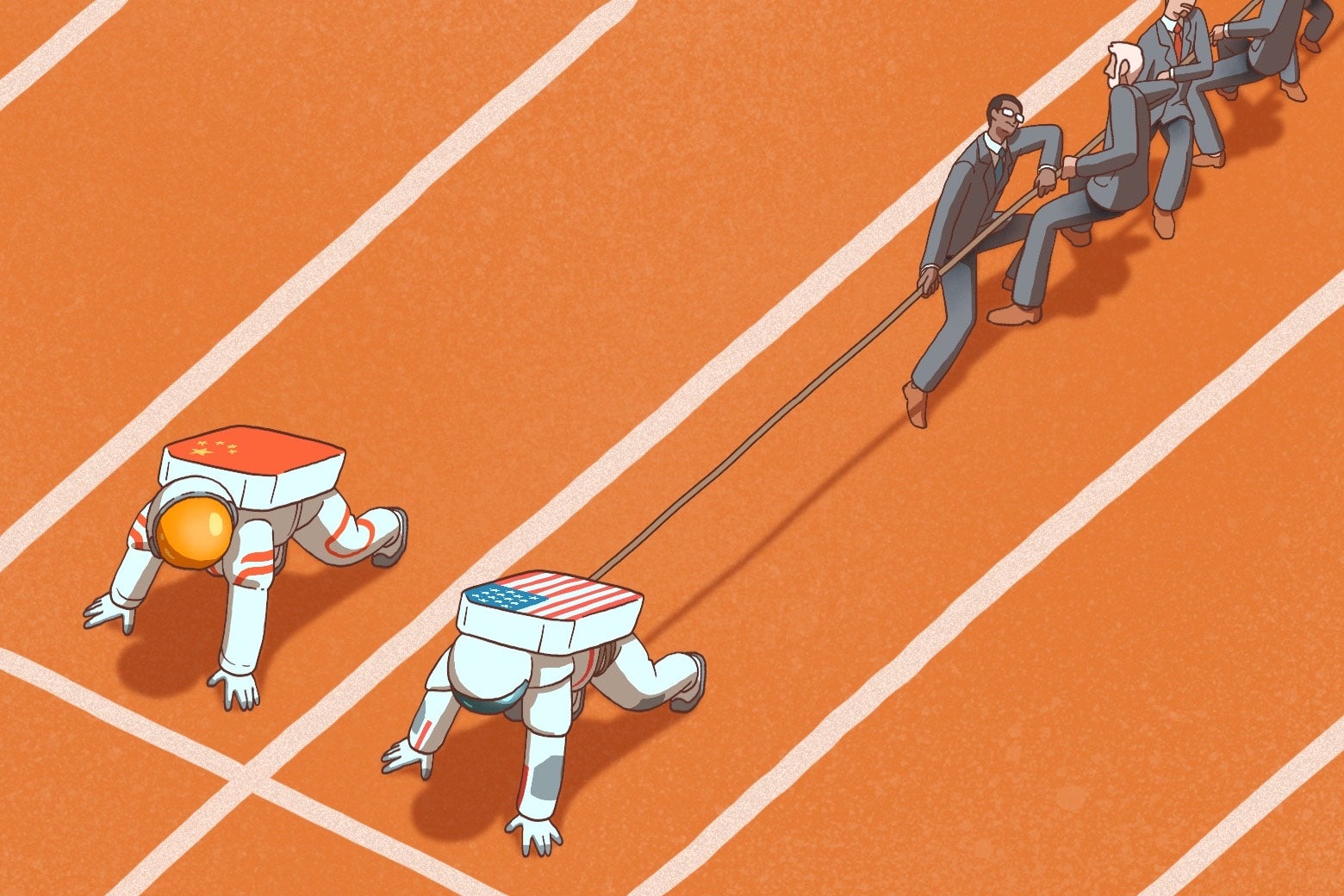

Yet NASA has struggled for two decades to explain and sell the moon mission to the public. The simplest elevator pitch is that we’re in a new space race with China.

Space, according to a lot of generals, hawkish politicians, and conservative think-tank folks, is the new “warfighting domain.” The United States and China covet its raw resources. The most abundant resources, in the form of water ice in permanently shadowed craters, are near the lunar south pole. Those resources could be exploited for long-term dominance in what some experts believe will become a trillion-dollar space economy that develops between the Earth and moon.

Illustration by Hua Ye

China has already landed robotic craft on the moon and has announced it will land people (taikonauts) there by 2030. And while China has a track record of sticking to its schedules, NASA timelines are typically written in evaporating ink. Everyone knows the 2027 landing goal is implausible. Indeed, Acting Administrator Duffy said on television recently that NASA will land astronauts before Jan. 20, 2029, the day President Trump would—under the Constitution, anyway—be required to leave office. But Duffy’s comments did not constitute official policy. The stated goal for Artemis is still a 2027 landing.

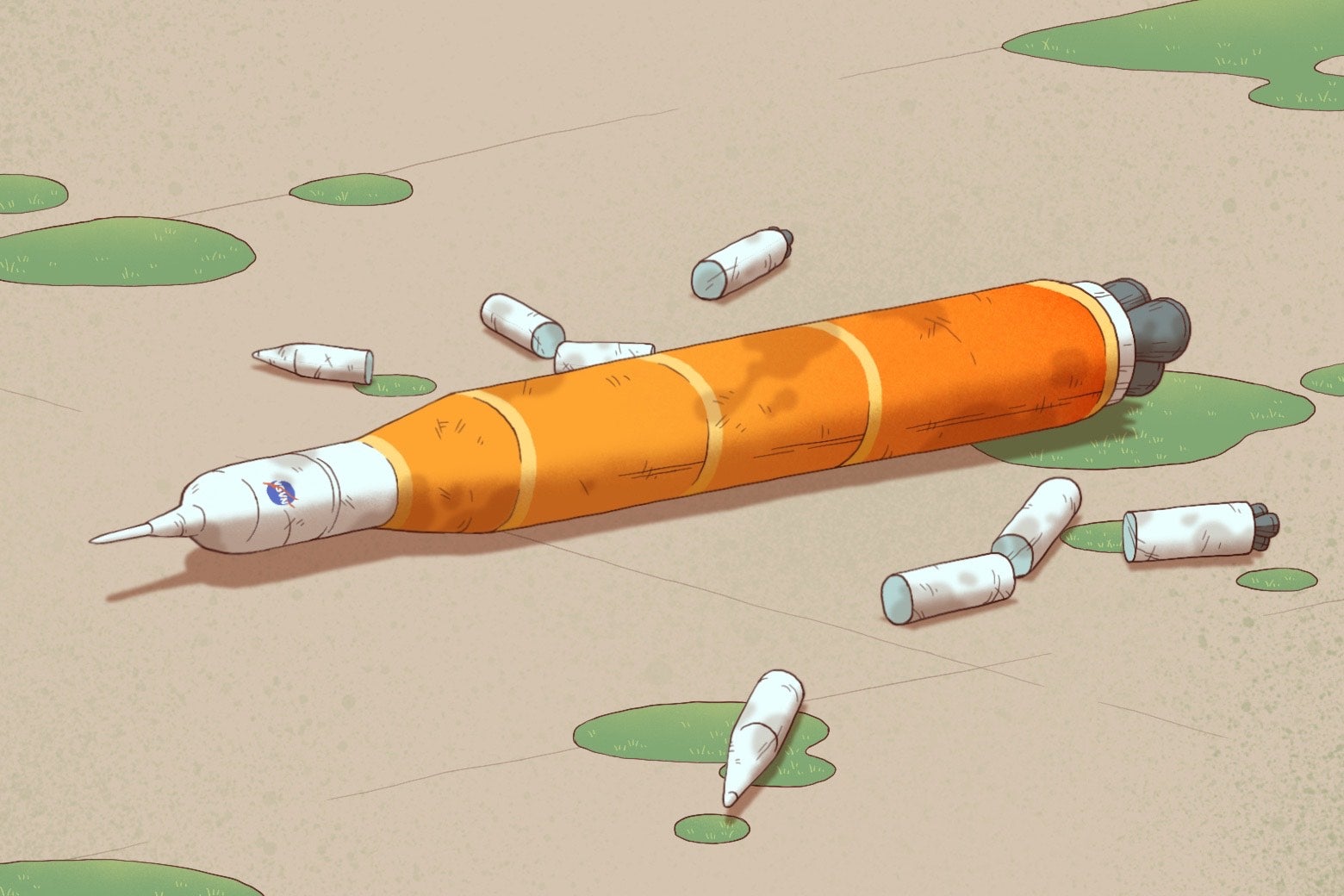

But how? NASA and Boeing have spent a decade and a half developing a jumbo rocket with the very creative name “Space Launch System,” or SLS. This is NASA’s moon rocket, able to boost heavy payloads—such as a capsule containing astronauts—into space.

NASA and contractor Lockheed Martin have also spent close to two decades developing a crew vehicle, a capsule named Orion, that can take astronauts to Earth orbit via the SLS rocket and then travel to an orbit of the moon. Despite being in development for so many years, across multiple presidential administrations, and at a cost to taxpayers of many tens of billions of dollars, the rocket and capsule have yet to fly with a crew. Each launch of the SLS and Orion is estimated to cost about $4 billion, and under NASA’s budget, it can afford to launch only once every two years.

Artemis I, an uncrewed flight, sent Orion around the moon three years ago, and it came back with damage to the heat shield. Artemis II is the upcoming crewed mission, a “flyby” that, if all goes well, will take four astronauts around the back side of the moon before they return to Earth. Artemis III is the landing.

But NASA doesn’t have a lander. Orion is not designed to land.

If you go on the NASA website, you can see an explanation of the Artemis III architecture and descriptions of a lander, including an artist’s rendition. It’s a modified upper stage of SpaceX’s huge Starship rocket. The lander is named Starship HLS, for Human Landing System.

No version of Starship has yet flown with a crew, not even in low Earth orbit, much less to the moon. And in the past two years, Starship has experienced several uncrewed test-flight failures, sometimes delicately referred to as “rapid unscheduled disassembly.” More recently, however, Starship had two test flights that were considered successful. That version of Starship won’t go to the moon, however; SpaceX is developing an even larger version with more engines, and that won’t be tested until next year.

Starship is already the largest rocket ever built. The upper stage—the part that, according to SpaceX and NASA, will be modified to serve as a lunar lander—is 165 feet tall. That is not a typo. Starship HLS is about seven times the height of the Apollo landers. During flight, astronauts will be in a crew compartment near the top. But after they touch down on the moon, they won’t be able to climb down a ladder to the surface the way Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin did on Apollo 11. They will have to take an elevator to the surface.

Why is SpaceX in charge of our lunar lander, anyway? Several companies competed for the fixed-price contract to build a lander, including Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, in partnership with legacy aerospace heavyweights like Lockheed Martin, collectively known as the “National Team.” Its bid was nearly $6 billion. But those legacy aerospace companies were in low regard at NASA due to the glacial development pace and the cost overruns of SLS and Orion. Meanwhile SpaceX was flying high. It had already proved to NASA that it could send cargo and astronauts to the space station, and was pouring its own money into the development of Starship. SpaceX said it could give NASA a lunar lander for a shockingly modest $2.9 billion, essentially a side hustle for the grander ambitions of Musk. NASA went with the low bid.

And here we are.

It is hard to overstate how complicated the current (and certain to change) Artemis plan is.

For the modified upper stage of Starship to serve as the lander, it will need a lot of fuel. The plan of record calls for SpaceX to launch many Starships in rapid succession to fill a tanker version of Starship in Earth orbit, a feat requiring cryogenic refueling in orbit, never before achieved. How many of these Starship launches will be needed is unclear. In 2023, a NASA official said it would be “in the high teens.” SpaceX has suggested it can do this with fewer launches. What’s certain is that, to limit inevitable fuel leakage, these launches would have to be conducted quickly, within just a few weeks of each other.

A separate Starship will then launch to Earth orbit, dock with the tanker, and fuel up for the moon voyage. Once it reaches lunar orbit, it will dock with Orion, where four astronauts (launched via SLS) will be waiting. Two of the astronauts will get into Starship HLS and descend to the moon’s surface for a roughly one-week sojourn. The astronauts will launch off the moon on Starship HLS to dock again with Orion, which will carry everyone home for a splashdown in the Pacific.

Illustration by Hua Ye

Critics, perhaps unsurprisingly, view this as Mission Improbable. There are so many rockets, so many untested elements, so many moving parts. In September, three former top NASA officials, all veterans of the human spaceflight programs who boast collectively more than a century of experience, published an op-ed in SpaceNews describing the current Artemis architecture as seriously flawed, asserting, “To us, it is indisputably clear that the plan for Artemis will not get the United States back to the moon before China.”

Former NASA administrator James Bridenstine, who served during the first Trump administration and is now a private aerospace consultant, said the same thing when he testified Sept. 3 before the Senate. “While the United States should celebrate orbiting the moon in 2026,” he said, “the United States does not have a lander. Unless something changes, it is highly unlikely the United States will beat China’s projected timeline to the moon’s surface.”

For many months, Artemis skeptics wondered how long it would take for NASA to admit that the trains weren’t running on time. That finally happened Oct. 20, when Duffy, who had initially denounced Bridenstine’s comments, went on television and said SpaceX is behind in the development of a lunar lander and he’s going to open up the contract and let other companies compete to build one. That raised the possibility that Bezos’ Blue Origin and its partners might yet get the Artemis III job. (After losing the initial battle against SpaceX, Blue Origin in 2023 managed to get a lander contract for Artemis V, envisioned as the third landing of astronauts.)

Musk, infuriated by Duffy’s comments, flung insults online, saying he has a “two digit” IQ. “Sean Dummy is trying to kill NASA!” Musk wrote.

SpaceX is a nimble company, with enough engineering talent to pivot quickly. In an update posted online Oct. 30, the company said it is “formally assessing a simplified mission architecture and concept of operations that we believe will result in a faster return to the Moon while simultaneously improving crew safety.” NASA—famously not nimble—may decide to put the Orion capsule in a lower orbit around the moon, which would lower the number of Starship fuel tanker launches and make it easier for the astronauts to return to Orion in an emergency, according to Doug Loverro, a former NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations and a co-author of the SpaceNews op-ed.

Duffy’s decision to reopen the lander contract “is step one of the 12-step process that they’re on, which is to admit they have a problem,” Loverro told me. “We were going to lose this race if we didn’t make some changes soon.”

This is all highly contentious stuff in the space community, with many stakeholders. And there’s almost more than one goal. NASA wants to put boots on the moon ASAP, before China gets there. But it also has grander long-term aspirations of establishing a permanent presence on the moon—and then we go to Mars.

As NASA’s difficult year nears an end, Artemis, the agency’s signature program, is a mess. If you have a plan that makes no sense, you don’t really have a plan. You’re going nowhere.

III. Waiting for Starship

You can see an Apollo lunar lander at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. The curator of the Apollo Collection, Teasel Muir-Harmony, gave me a tour recently, and we spent a lot of time staring at one. It’s a test version, a near-duplicate of the Eagle that put Armstrong and Aldrin on the moon and launched them back into lunar orbit.

The more you look at it, the weirder and more marvelous it is. There are no wings, fins, or other aerodynamic features. It’s unlike any other flying vehicle you will ever see.

“It was designed for one thing—the needs for a lunar landing,” Muir-Harmony said.

Few even realize how hard it was to pull off the Apollo program. In the American imagination, President John F. Kennedy said let’s put a man on the moon before the decade is out (“and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard”—beautiful line), and then inexorably we got there, in peace for all mankind.

It was never inexorable. The public didn’t know all the struggles, the delays, the doubts. The lunar lander was the biggest headache. Grumman built it under a NASA contract, and raced against the clock. Because it wasn’t ready in 1968, NASA decided that Apollo 8 would send three astronauts to orbit the moon and bring them home without landing—similar to what NASA says it is planning to do no later than this coming April.

Back then, the political establishment and the general public were not united behind Apollo. There was a war going on, anti-war protests in the streets, the Civil Rights Movement. The space program carried more than a whiff of a military operation.

Not even Kennedy was totally sold on the lunar landing. He feared it was a stunt and not worth the cost and political capital. He toyed with the idea of teaming up with the Soviets on a joint lunar mission, even proposing it in a speech at the United Nations. That would make the moon race one he couldn’t lose.

In his fine book One Giant Leap, Charles Fishman suggests that America would not have reached the moon before the end of the decade were it not for what happened in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. NASA responded to the assassination by ensuring that the martyred president’s vow would become a reality.

NASA was briefly handed nearly 5 percent of the entire federal budget in the effort to beat the Soviets to the moon. The Cold War felt very hot. With money, public support, and an ambitious but doable mission, NASA put together a stunning step-by-step program that sequentially put Americans closer and closer to the goal, realized on July 20, 1969, after some last-minute boulder-dodging by Armstrong as the Eagle neared the lunar surface.

In the decades since, the NASA budget has been generally flat, and only about a tenth of what it was as a percentage of federal spending during the peak of the Apollo years. The budget crunch began even during the initial moon program, when NASA canceled the final three planned Apollo missions.

So where would NASA go after the moon? Mars remained Mars: too far, too hard, too expensive. NASA decided to build a space shuttle, a taxi to low Earth orbit, promising that spaceflight would become routine and affordable. In fact, it was an expensive and risky business still—as the horrific loss of the Challenger shuttle and its crew on Jan. 28, 1986, demonstrated all too vividly. The explosive demise of the shuttle was carried on live television as children across America hoped to see astronaut Christa McAuliffe become the first teacher in space.

Addressing the nation that night, President Ronald Reagan said, “I want to say something to the schoolchildren of America who were watching the live coverage of the shuttle’s takeoff. I know it is hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It’s all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It’s all part of taking a chance and expanding man’s horizons. The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave.”

The shuttle kept flying. In the following decade NASA and its partners started building the International Space Station. But then on Feb. 1, 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry into the atmosphere, killing the crew of seven. NASA was forced to rethink its entire human spaceflight strategy. The shuttle had to go. And the moon was back in play. In 2004, President George W. Bush said America would have boots on the moon by 2020. And that would be, of course, a stepping stone to Mars:

We will build new ships to carry man forward into the universe, to gain a new foothold on the moon, and to prepare for new journeys to worlds beyond our own. … With the experience and knowledge gained on the moon, we will then be ready to take the next steps of space exploration: human missions to Mars and to worlds beyond. As our knowledge improves, we’ll develop new power generation propulsion, life support, and other systems that can support more distant travels. We do not know where this journey will end, yet we know this: human beings are headed into the cosmos. [Emphasis added.]

But elections have consequences and the cosmos would have to wait. The moon program, called Constellation, did not survive the coming of the Obama administration. A blue-ribbon panel concluded that the human spaceflight program was on an unsustainable path: “It is perpetuating the perilous practice of pursuing goals that do not match allocated resources.

Space operations are among the most complex and unforgiving pursuits ever undertaken by humans. It really is rocket science.”

OK—if not to the moon, where would NASA send its astronauts? In a speech at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in 2010, President Barack Obama suggested that astronauts would orbit Mars in the “mid-2030s” and added that “a landing will follow,” offering no specifics. And in the meantime—a very long meantime—“we’ll start by sending astronauts to an asteroid for the first time in history,” Obama said. Buzz Aldrin was present as Obama spoke these words. “I understand that some believe that we should attempt a return to the surface of the moon first, as previously planned,” Obama said. “But I just have to say pretty bluntly here: We’ve been there before. Buzz has been there.”

The asteroid idea went nowhere. NASA quickly calculated that, because asteroids orbit the sun, any human mission to visit one would likely take the better part of a year. Instead, NASA crafted the Asteroid Redirect Mission, a proposal to grab a boulder from an asteroid with a robotic spacecraft and haul it back to lunar orbit. Astronauts would fly to the moon, perform a spacewalk, obtain samples of the boulder, and then rocket back to Earth.

None of that happened. It was a complex mission that seemed primarily intended to give the human spaceflight program something new to do.

Another round of “elections have consequences”: President Trump revived the lunar program in 2017. In 2019, the program got its name, Artemis, with a 2024 landing as the goal.

As my former colleague Christian Davenport reported in his new book Rocket Dreams, NASA administrator Bridenstine had the smart idea of bringing in international partners in what is known as the Artemis Accords. The moon program now has a diplomatic element, at last count involving 56 nations that have signed onto a set of agreements and norms for lunar activities in the decades ahead. Although Joe Biden barely mentioned space when he ran in 2020, this time the new administration did the unusual thing of not yanking NASA around once again. Artemis stayed intact.

Now the program’s problems were entirely internal. The architecture of Artemis has been a dog’s breakfast, glopping together a bit of this and that, including “heritage hardware” derived from the Shuttle program. By 2019, NASA had already invested billions of dollars in the SLS rocket and the Orion capsule, and any Artemis architecture had to incorporate that taxpayer-owned hardware just for appearances’ sake.

And where was the lander?

“Artemis was announced by Pence and Trump without any reality,” Lori Garver, the deputy administrator for NASA in Obama’s first term, told me. “Whether they said ’28 or ’24, there wasn’t a lander, there wasn’t a suit. We had a rocket and capsule, which, by the way, couldn’t get there. We in the space community, in my view, have been willing to engage in magical thinking this whole time.”

The current architecture of Artemis “does not make sense,” added Robert Zubrin, a passionate advocate for human spaceflight and the founder of the Mars Society. The elements “don’t fit together. It’s five separate elements which have each been funded for different reasons.”

Casey Dreier, the head of space policy for the nonprofit Planetary Society, said the same thing about Artemis: “It’s optimized for political coalition building.”

When Apollo 11 landed on the moon, in a vehicle optimized for precisely that purpose, the legs, designed with a crushable honeycomb interior, were supposed to contract. But Armstrong set the Eagle down so softly that the legs barely contracted, and the bottom rung of the ladder remained roughly two and a half feet above the surface. One of the first things Armstrong had to do when he stepped off the ladder and onto the Eagle’s footpad was make sure he could jump back to that bottom rung.

As Garver put it: “When they’re talking about the elevator—how many things could go wrong? We’ve all heard Buzz and Neil talk about how big that last step was.”

Artemis has another critic, and he is the richest man in the world.

Elon Musk is no fan of Artemis as currently designed. Late last year, he wrote on X, “The Artemis architecture is extremely inefficient, as it is a jobs-maximizing program, not a results-maximizing program. Something entirely new is needed.” And in October, on the same platform, Musk wrote, “Starship will end up doing the whole Moon mission. Mark my words.”

Except Starship is nothing like the Apollo lander. It’s a multi-purpose vehicle designed for heavy payloads. The new version of Starship under development is optimized for putting SpaceX’s next generation of Starlink satellites in low Earth orbit and is “not optimized for those deep-space missions,” according to Todd Harrison, a space policy expert at the American Enterprise Institute. SpaceX is seeking government permission for as many as 44 Starship launches a year from the Kennedy Space Center, and another 76 a year from the adjacent Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. If that happens, it’s going to get loud on the Cape—window-rattling loud. The birds at the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge aren’t going to be happy. Many locals are pushing back. This isn’t the 1960s. The Space Coast population has boomed, and Port Canaveral is the busiest cruise ship port in the nation.

The profits from the next generation of Starlink satellites could help Musk advance his plan to send people to Mars via hundreds and eventually thousands of Starship launches. But Harrison said SpaceX would need NASA funding and infrastructure for its long-term goals. “The reason SpaceX needs NASA to go to Mars, even with all the free cash they’re generating, is that it’s not close to the amount they’d need to actually set up a sustainable colony on Mars,” he said.

Musk, who has said he was inspired by Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series of science fiction novels, believes that we have a narrowing window of opportunity to prolong humanity’s existence. By creating a fully independent civilization on Mars—with a million Martian settlers at least—we could sustain the “candle” of human consciousness and provide a hedge against an existential catastrophe on Earth.

I don’t doubt that Musk and his talented engineers are capable of at least sending human beings to Mars in the coming years. It strikes me as reckless and borderline homicidal, but I have been wrong about Musk before. When I first interviewed him in 2005, he seemed a dreamer with little hope of success and had never launched a single rocket. But NASA in 2008 gave SpaceX a fixed-price contract to send cargo to the International Space Station. This new way of doing business—a “commercial” contract in which NASA wouldn’t own the hardware—proved historically consequential. NASA was buying a service, akin to purchasing a plane ticket. From there, Musk and his motivated workforce created a sensationally successful rocket company, the runaway leader in a burgeoning commercial space industry. Thanks to reusable boosters, SpaceX has lowered launch costs dramatically, won billions of dollars in NASA and national security contracts, and today dominates the global launch business.

The Mars goal is one reason Musk, who formerly supported Democrats, pivoted to Trump last year. Musk abhors the federal bureaucracy that he believes is slowing development of Starship, and thus our migration to another world. The dream of a Mars civilization shows why the installation of an ally like Jared Isaacman at NASA was so crucial to him.

IV. The Visionaries

What exactly are we doing in space, anyway? What’s our future as a spacefaring people? Is it the destiny of humanity—as many people have claimed for the better part of a century—to spread across the solar system, to settle distant worlds and journey to the stars?

Like many people who grew up in the 1960s, I assumed human spaceflight in our solar system would become routine. We believed in the “conquest of space,” that Star Trek was a plausible version of life in the 23rd century. We saw the conquest unfolding before our eyes, in real time. John F. Kennedy set a firm goal—boots on the moon before the decade was out—and NASA did it, thrillingly.

The cosmos was open for business. That was the thinking.

And what a cosmos it is. In the past century, astronomers discovered that the Milky Way is not the only galaxy, but just one of countless “island universes.” In 1995, the first planet orbiting a distant sun-like star, an exoplanet, was discovered, and now we know that planets—and planetary systems like our own—are common. In that same year, astronomer Robert Williams aimed the Hubble Space Telescope for 10 days at a seemingly empty patch of night sky only about 1/30th the diameter of the moon. The resulting image showed several thousand galaxies crammed into the Hubble’s small field of view. Astronomers now know there are tens of billions of galaxies at least. The universe might even be infinite.

We’re kids staring into the window of the cosmic candy store. And this mind-boggling universe forces us to ponder how we fit into this grand creation.

The universe asks: Who are you, exactly, how do you matter? Why are you even here?

And what are you gonna do now?

Such questions call for an oracle, a big thinker, a visionary. I used to ring up Freeman Dyson, the famed physicist, at the slightest excuse. He was always easy to reach in his office at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and he could be counted on to say something arresting about the future. He was quite certain we would be a spacefaring species facing no boundaries.

Dyson, who died in 2020 at 96, was a technophile with interstellar dreams. In the late 1950s, he worked on Project Orion, a collaborative effort to build a starship powered by small atomic bombs. The slogan of Dyson and his colleague Ted Taylor, a Princeton University physicist, was “Saturn by 1970.” Mars, they originally figured, could be reached by human beings in 1968, he wrote in his 1979 book Disturbing the Universe: “For Ted and me the words ‘Saturn by 1970’ were not just an idle boast. We really believed we could do it if we were given the chance. We took turns looking at Jupiter and Saturn through a little telescope that Ted kept in his garden. In our imagination we were zooming under the arch of Saturn’s rings to make the last braking maneuver before landing on the satellite Enceladus.”

Project Orion was canceled after the Test Ban Treaty of 1963 prohibited nuclear weapons in space. But Dyson never gave up hope that we’d roam the solar system. He believed we needed to go to space for three reasons: shifting industrial processes to space so that, in his words, “the earth may remain a green and pleasant place for our grandchildren to live in”; resources, including solar energy, minerals, and living space; and finally, “our spiritual need for an open frontier.”

Some of his ideas were a bit … fantastic. In 1998, he told me that we would someday live in the Oort Cloud. The Oort Cloud does not yet show up on Google Maps, but it’s out there, a realm of icy objects and comets, trillions of them, far beyond the orbit of Neptune. Dyson said the Oort Cloud has more real estate than all the planets in our solar system, and therefore we’ll eventually find a way to adapt to life there.

“Probably we’ll be a million species before long,” he said, suggesting that genetic engineering of human beings would enable colonization of the solar system. “For example, if you want to run around naked on Mars, you’d need a thick skin. I can imagine our descendants on Mars will be more like polar bears. We might decide to grow fur to keep warm rather than sitting in space suits.”

In April 2014, I visited Dyson at the Institute for Advanced Study, where he spent much of his long career and, at 90, was oracular as ever. I asked him what most surprised him about life in the 21st century.

“I would say the failure of space as a human adventure,” he said. “That we’re still not going anywhere in space as human beings. I think that’s sort of the big surprise. I’d taken it for granted that we’d be wandering around the solar system by now.”

But things take longer than expected. The great popularizer of space travel, Arthur C. Clarke, co-wrote the screenplay, with director Stanley Kubrick, for 2001: A Space Odyssey, which envisioned Pan Am flights to the moon at the millennium, along with a moon base and astronauts flying to Jupiter. In his 1968 book The Promise of Space, Clarke wrote that a permanent base on Mars might be established before the end of the 20th century. “On Mars, domes a thousand feet or more in diameter could easily be constructed,” he wrote. “Inside these great bubbles of air the explorers, or colonists, would live in a shirt-sleeve environment; only when they went outside would they have to wear pressure suits or travel in closed vehicles.”

The spaceships of the future—the ones we imagine, or design on paper—have the signature feature of never blowing up. Orbital space colonies, such as the ones envisioned by Gerard O’Neill, the Princeton professor who wrote The High Frontier and inspired Jeff Bezos to get into the aerospace business, never have a catastrophic failure. The visionaries of the early Space Age didn’t worry much about solar radiation, coronal mass ejections, galactic cosmic rays, psychological stress from isolation, and cost-benefit ratios.

Illustration by Hua Ye

Clarke floated the idea of sending an “ark” containing human germ cells into deep space, aimed at a planet orbiting a distant star many light years away. They could then be fertilized before journey’s end, and the babies raised “under the tutelage of cybernetic nurses who would teach them their inheritance and their destiny when they were capable of understanding it.” They’d reach maturity in time to explore the planet.

Clarke acknowledged the questionable morality of such a project, consigning these explorers to an “onerous and uncertain future.” But future societies may have no qualms. “What to one era might seem a coldblooded sacrifice might to another appear a great and glorious adventure.”

Or it might always seem a coldblooded sacrifice to a civilization that has not lost its mind.

V. Snap Back to Reality

Space hasn’t been a failure at all, in truth. It’s just different from what Dyson and Clarke anticipated.

We’re a spacefaring civilization to a stunning extent. But we rely heavily on robotic spacecraft rather than astronauts.

Thousands of satellites orbit the Earth—some in high “geostationary” orbits that keep them over the same spot on the surface, something Clarke predicted in 1945. Our daily lives increasingly depend on space hardware. A violent solar storm can generate an eruption of particles and magnetic fields, known as a coronal mass ejection, that if aimed directly at Earth could damage satellites and the power grid on the surface. That’s one reason NASA and NOAA launched probes in September that will monitor space weather.

NASA has also explored all corners of our solar system with the Mariner, Pioneer, Viking, Voyager, Cassini, Galileo, Juno, Magellan, and New Horizons probes, among many other robotic spacecraft. NASA has explored the surface of Mars with five different rovers. The Parker Solar Probe has flown within shouting distance of the sun. NASA is currently developing Dragonfly, a mission that in a few years will send a car-sized vehicle called an “octocopter” to explore the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan.

NASA’s science portfolio has inspired people around the world and brought talent to America. And Trump and his allies want to blow it all up. Trump’s requested budget cuts would decimate NASA science while funneling precious dollars to the troubled human spaceflight program.

A veteran of NASA science missions told me something I didn’t realize: Robotic spacecraft circling distant worlds or racing toward interstellar space can’t be turned off and then turned back on. So if funding is cut to a mission, under NASA procedures, the mission leaders have to develop a plan for shutting it all down, including all communications. If that happens and Congress later says, Wait, we screwed up, start it up again—it’s too late, because the spacecraft is no longer able to be contacted.

“It’s the death penalty for robots,” the scientist said.

Human spaceflight hasn’t been a failure, either. The International Space Station has been continuously occupied for more than a quarter of a century. We may yet zoom across the solar system. The question is where to go from here.

Why not at least try to build one of O’Neill’s orbital space colonies? Or try to carry out Musk’s dream of a full-blown civilization on Mars? The advocates for space settlements, such as members of the National Space Society, greatly outnumber the skeptics. It’s an exciting vision, and arguably an existential necessity, because at some point Earth could have a really bad day—such as a Chicxulub-scale asteroid impact. “Dinosaurs didn’t have a space program,” as blogger Casey Handmer wrote.

The case against space settlements has been laid out comprehensively and quite amusingly by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith in their 2023 book A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? The book essentially answers: maybe not, probably not, and no.

The Weinersmiths, who describe themselves as space nerds, had intended to produce a book favorable to the idea of space settlements. Their research led to the conclusion that settling space is not only wildly more difficult than its advocates believe, but also would lead to dangerous geopolitical conflicts here on Earth.

One by one, the authors attempt to demolish the orthodoxies of space enthusiasts. Space, they write, “is terrible”—an awful environment for human beings, compared to Earth. The only virtue of Mars is that it’s not as terrible as the moon.

“With enough time and effort, Mars at least holds out the possibility of a second independent home for humanity. But it sucks,” they write.

Robert Zubrin founded the Mars Society nearly three decades ago—I was there in Boulder, Colorado, at the first raucous gathering—and remains an enthusiast for human missions to Mars. He’s dismayed by NASA’s recent failures and, surprisingly to me, does not think Musk and SpaceX should go it alone and carry out a private Mars mission. This needs to be something we all do together, he wrote earlier this year. The purpose of settling Mars, he believes, is to establish a new creative branch of human civilization. No one should be under the illusion that a Mars settlement, even with a million people, could be fully independent of Earth and entirely self-sustaining.

“And besides, the idea that a few will survive on Mars, while billions die on Earth is so morally repulsive that any programme foolish enough to adopt it would be doomed,” he wrote. “Coated with ideological skunk essence, the mission’s protagonists would appear more like the selfish characters in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, dancing in a castle while everyone outside dies in an epidemic, than the heroes of Foundation.”

VI. The Best of All Possible Worlds

The great enterprise of space travel led to an intensified appreciation of Earth. The environmental movement gained strength in tandem with the Space Age. The first views of the Earth from space told us something profound. As Carl Sagan wrote, “Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that there is anyone who will come and save us from ourselves.”

Earth is a remarkably congenial rock for human beings and other life forms. For more than six decades, NASA has been sending robotic probes across the solar system, and perhaps the most stunning discovery is that there is nothing in our little cosmic cul-de-sac that looks like Earth. Not even close.

NASA has played a key role in revealing that planets are common. But even with the acute vision of the James Webb Space Telescope, we haven’t seen anything as life-friendly our home. NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory, if it survives the budget axe, could someday spot one. There’s got to be an Earth 2.0 out there somewhere. There could even be one relatively close in the cosmic scheme of things. But in our own solar system, there’s Earth and … nothing remotely comparable. Instead, there are scores of planets and moons where humans, if exposed to local conditions without life support, would perish immediately. We’d be frozen stiff, or baked at 800 degrees Fahrenheit, or explode, or some combination of the above.

Illustration by Hua Ye

A big lesson since Sputnik launched the Space Age is that we are Earthlings to the core. We learned this through astronomy, robotic exploration and—yes—human spaceflight. We learned that zero gravity is harsh on the human body, which has been shaped by natural selection to live on the land surface of this particular rocky planet, in this particular orbit around this particular star.

Can humans live in space or on another planet? Of course they can, if buffered sufficiently in technology. Someday Mars might be terraformed to make it more Earthlike. Or humans could be genetically altered to live there. We could become those Martian polar bears.

But I’d wager that anyone who lived on Mars would appreciate all the more the beauty and congeniality of our own planet.

The future is always up for grabs, open territory, a boundless frontier. The one thing we know is that it will surprise us. What will preoccupy us in a century, fuel our ambitions and stir our fears, will probably be something we can’t even imagine today. So what I say next is vulnerable to an existence proof: For the foreseeable future—our children’s lifetime, at least—there is no plausible Plan B for human beings. Earth is our home, and we have to protect it. Failure is not an option.

Go for a walk in the woods sometime and breathe that air with 21 percent oxygen. Listen to the birds. Smell the riotous life all around you. Appreciate the variety of ways a planet might be, and how many of them are, cold, dry, sterile, baked, toxic, inhospitable, and, as far as we can tell, completely devoid of life. Think of our astonishing good fortune to live on a planet capable of sustaining life for 4 billion years, allowing natural selection to create what Darwin called “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.” Find moments in your busy life to embrace the beauty of being a living, sentient, thoughtful, sensate organism.

I recognize that many people want more than that. They want the novelty and adventure of exploration, not cozy nights by the hearth drinking hot cocoa. Good luck, friends, your starship awaits.

America’s Journey in Space Is About to Face Its Most Consequential Moment in Half a Century. Everyone Agrees: It’s a Complete Disaster.

How Many Kids Will Have to Die for RFK Jr. to Be Stopped?

This Content is Available for Slate Plus members only

This Huge Childhood Health Issue Is, I’m Delighted to Say, Majorly Improving

It Kills Thousands of People Every Year. You Probably Did It This Morning.

I once asked James Cameron, the director and adventurer, why we should travel to Mars and such places. He said: “Because it’s in our nature.” Some years later, you may recall, he made a solo dive in a submersible to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. That was in his nature.

I tend to get a little jittery if I’m more than 20 miles from a Starbucks. That may color some of my thinking about space settlements on distant worlds and human spaceflight generally. In case it wasn’t clear: I don’t want to go to the moon. I don’t want to live on Mars. And I definitely don’t want to live in the fucking Oort Cloud.

Reagan was right when he said, on the night of the Challenger disaster, that the future belongs to the brave. But it also belongs to the rational, the clear-eyed, the wise.

There’s a lovely passage in Dyson’s book Infinite in All Directions: “As a working hypothesis to explain the riddle of our existence, I propose that our universe is the most interesting of all of possible universes, and our fate as human beings is to make it so.”

With apologies to Dyson, here’s an alternative working hypothesis: We live on the best of all possible worlds, and our fate as human beings is to save it.