A decade after being listed among the UK’s rarest invertebrates, one of Europe’s largest native spiders is rapidly reclaiming wetland territory. The great raft spider (Dolomedes plantarius), once feared extinct in much of its range, now shows evidence of a sustained and expanding recovery across the United Kingdom and parts of continental Europe.

New population estimates report more than 10,000 breeding females in Britain alone—a figure made possible by targeted captive breeding and wetland restoration initiatives. In France, the species has been confirmed in over 20 administrative departments, indicating a far wider distribution than previously recorded.

This unexpected resurgence is prompting renewed interest in how precision rewilding, when combined with habitat engineering, can influence biodiversity at scale. It also raises new questions about long-term viability: can reintroduce species like D. plantarius survive without continuous intervention?

From Test Tubes to Thousands: How Captive Breeding Brought Them Back

Just over ten years ago, Dolomedes plantarius was clinging to survival in Britain. Wetland drainage and expanding farmland had left only a few isolated populations, with critical habitats shrinking by the year. In response, Chester Zoo launched a pioneering spider conservation program, collaborating with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) to rear young spiderlings in a controlled lab setting.

Each spider was raised individually in test tubes to prevent cannibalism and fed by hand—one fly at a time. Once mature, they were released into newly restored wetland reserves. This meticulous process, started in 2011, is now credited with one of the UK’s largest invertebrate recoveries.

The RSPB now estimates over 10,000 adult females have established themselves in wetland habitats across the country, including sites like Mid Yare and the Pevensey Levels. The spiders are not only surviving—they’re thriving in sufficient numbers to impact the local food web, controlling insect populations and even feeding on small fish and tadpoles.

Elsewhere in Europe, populations are also being tracked. A 2016 study confirmed the species’ presence in 22 departments across France, including regions such as Normandy, Picardy, and Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Rediscoveries in these areas suggest that small, fragmented populations may have persisted undetected for years, supported by the reestablishment of suitable aquatic environments.

This expanding distribution is supported by data from the species’ detailed ecological profile on Wikipedia, which confirms that Dolomedes plantarius has also been documented in countries across northern and central Europe, including Sweden, Germany, and the Baltic states.

Designed for the Water: A Predator Built for the Marsh

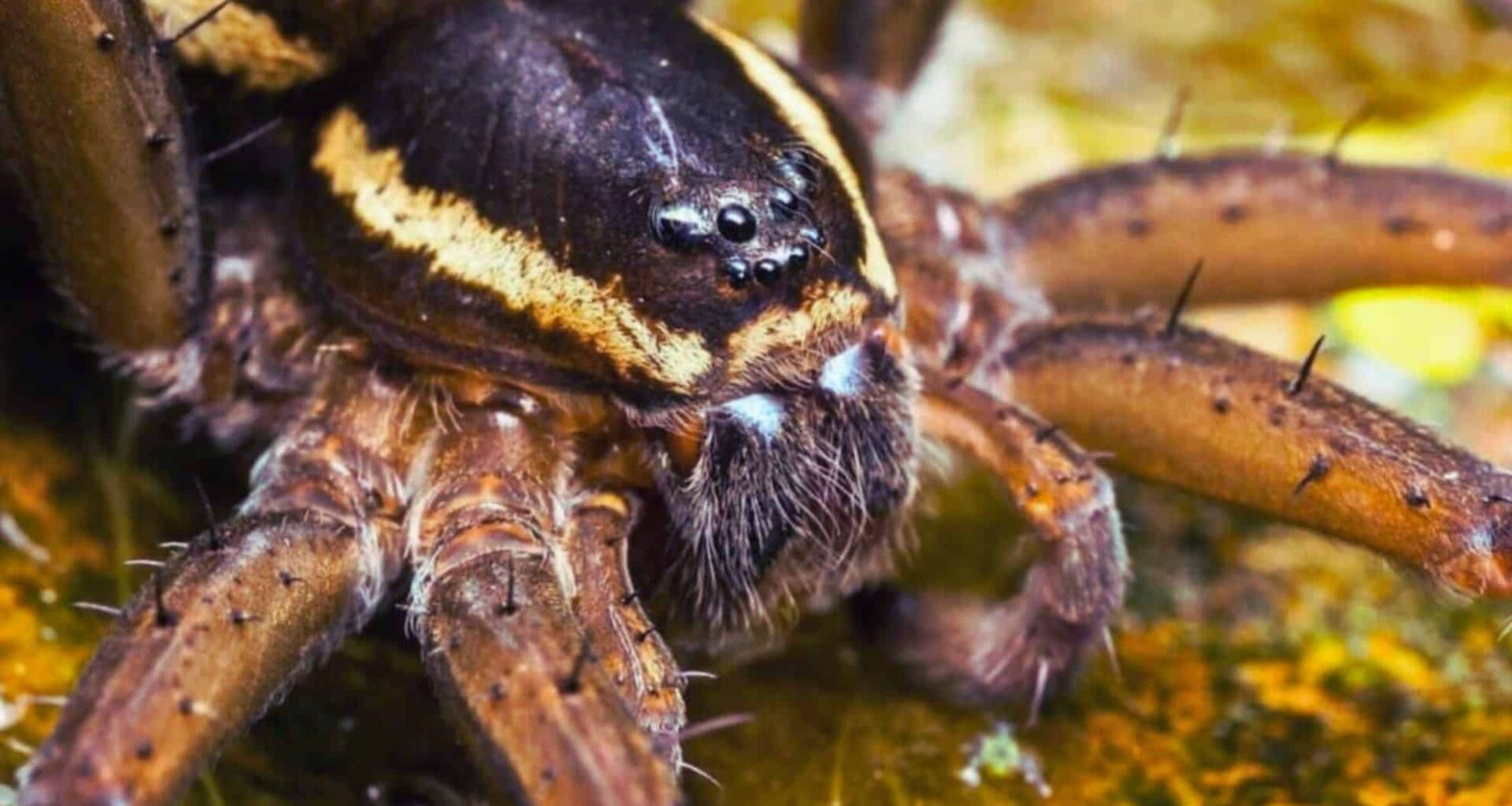

Unlike most spiders, Dolomedes plantarius doesn’t spin webs to catch prey. Instead, it uses specialized sensory hairs on its legs to detect vibrations on water surfaces. The spider positions itself with its rear legs on plant stems and front legs extended onto the water, waiting to ambush anything from aquatic insects to small vertebrates like sticklebacks.

Adult females can reach up to 7 cm in leg span, with dark brown bodies and striking white or cream stripes. Their unique biology allows them to not only walk on water but also dive beneath it to hunt or evade predators. They play a crucial role in wetland biodiversity, helping regulate insect populations and contributing to the ecological stability of marshes and ditches.

Their breeding behavior is equally specialized. After mating on water surfaces, females carry their egg sacs for several weeks, periodically dipping them into water to maintain moisture. Once ready, they build a nursery web above the waterline to guard their offspring before they disperse.

Despite their size, these spiders are harmless to humans and remain strictly confined to natural habitats. They do not venture into urban areas or homes, staying within the boundaries of marshes, fens, and riverbanks.

Thriving Now, but Still Vulnerable

This resurgence is promising, but not without caveats. The great raft spider remains listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, with its survival still tied closely to the health of its wetland habitats. Pollution, water extraction, and changes in land use policy all pose persistent threats.

France’s populations, though expanding, are not as robust. Habitat degradation and limited monitoring have made it difficult to assess true numbers. Even in the UK, where protection is legally enforced under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, continued management is essential to prevent backsliding. These spiders are heavily reliant on stable water quality and specific vegetation for breeding and hunting.

The species’ dependence on restored and artificially maintained wetland habitats means its future is not guaranteed by ecological conditions alone. Ongoing support through conservation budgets and public policy will be required to ensure continued success.