FEW ANIMALS scare full-grown African elephants. But bees are among them. So it was to bees that Iain Douglas-Hamilton looked when he sought to draw a line between those pachyderms’ domain and humanity’s. The farmers of Samburu, the Kenyan county where his research was based, bear elephants no ill will as long as the beasts keep out of their smallholdings. But the elephants do not know that. Bee fences—hives established at regular intervals on a farm’s perimeter—not only deter the interlopers, they also yield a mellifluous profit.

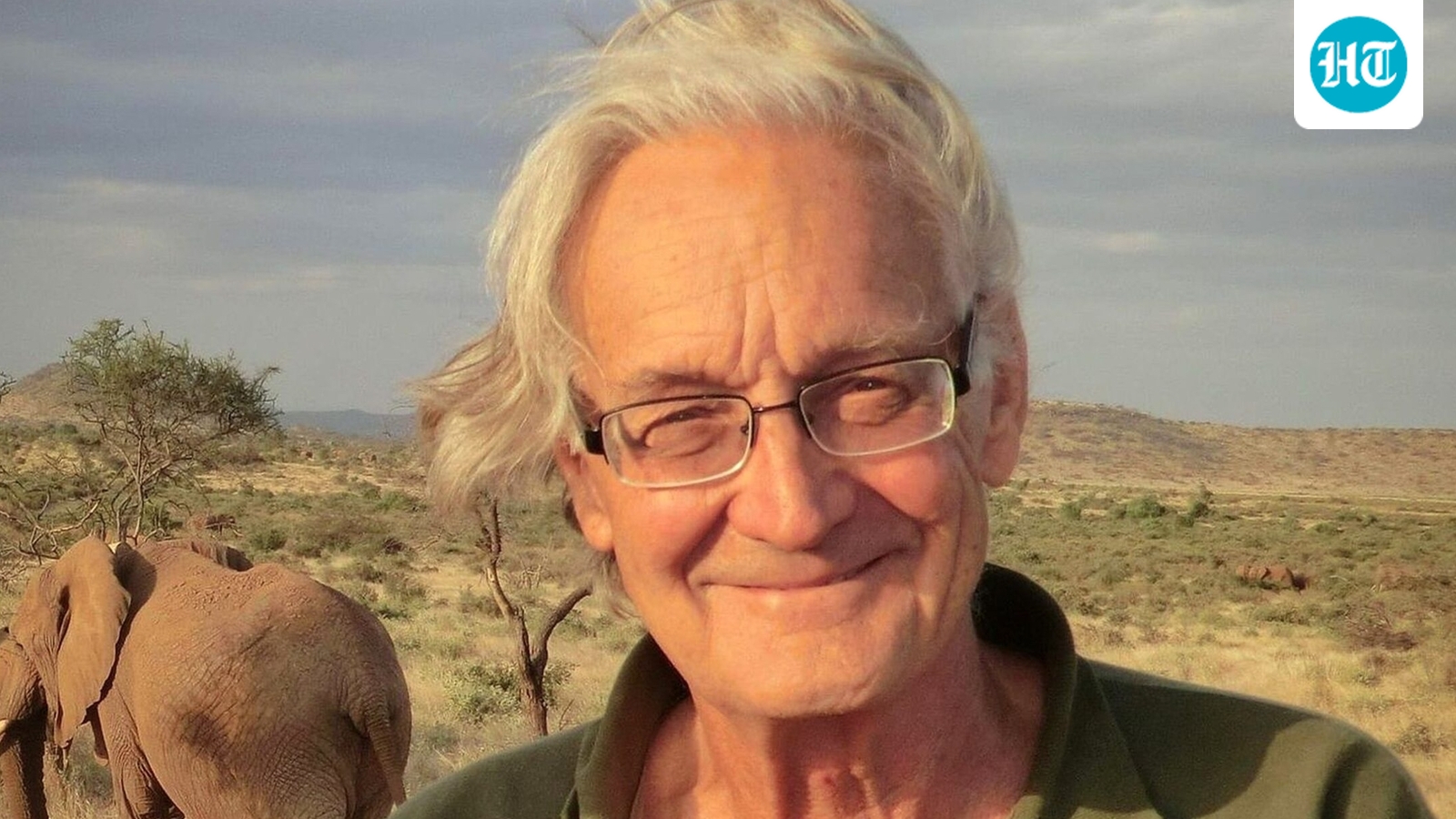

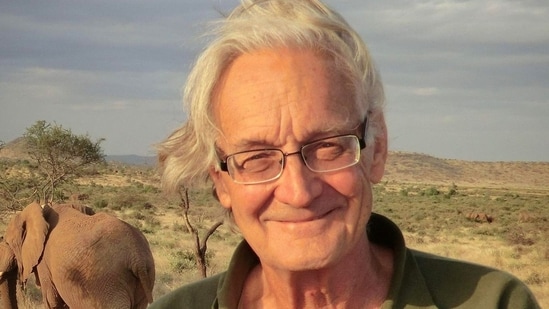

PREMIUM Iain Douglas-Hamilton (X/@EPIAfrica)

PREMIUM Iain Douglas-Hamilton (X/@EPIAfrica)

Irony of ironies, then, that it was bees which did for him. He was attacked by a swarm of them in February 2023. They almost killed him there and then, not least because, as a soldier might throw himself on a grenade to save his comrades, he threw himself over his wife, Oria, to shield her from the hymenopteran assault.

As tough as the pachyderms he studied, he survived. But he never truly recovered from the long shadow of anaphylaxis. And with his death, though they know it not, the world’s elephants have lost their stoutest defender.

It is said that the English conquered the British empire but the Scots ran it. So it was no surprise that Dr Douglas-Hamilton, grandson of a Scottish duke and son of a second-world-war Spitfire pilot, should pitch up in Tanzania in 1965, fading though the empire by then was. He came, however, not to rule (Tanzania was now independent), but to help. He was studying zoology at Oxford under the watchful eye of Niko Tinbergen, one of the founders of ethology. The ethologists’ radical idea was to look at what animals actually get up to in the big, bad world, rather than studying their actions when they are locked in boxes that dish out rewards and punishments, as the so-called behaviourists across the pond in Harvard were doing under the tutelage of B.F Skinner.

Those were days of zoological opportunity, when the future alpha males and females of the field were starting their careers: Jane Goodall (chimpanzees); Dian Fossey (gorillas); George Schaller (lions); Hans Kruuk (hyenas); Burney Le Boeuf (elephant seals). In that scramble for species, though, elephants were as yet unclaimed. Dr Douglas-Hamilton made them his own, hunting them not as his forebears would have done, with rifles, but with field glasses and a notebook.

Gradually, he got to know his quarry as individuals, each with their own particular quirks, in a way that Skinner and his acolytes could not possibly have conceived of doing with their lab rats. Anwar, a young male obsessed with cars. Frank, a bull who loved mountaineering. Monsoon, another mountaineer, who liked to take her kids along for the ride. Alpine, a female who often adopted orphans.

But it was when he added a plane (a Cessna, rather than a Spitfire) to his inventory that things really took off. Aerial censuses across the continent, using the methods he developed behind the joystick, began to show just how much damage ivory poachers were doing to elephant populations. And thus his true life’s work began. Saving the beasts became as crucial as studying them.

The numbers were horrifying. The censuses showed Africa’s elephant population crashing in number from 1.3m in 1979 to 600,000 in 1989. Dr Douglas-Hamilton became their advocate. His testimony to America’s Congress, for example, helped lead to the passing, in 1988, of the African Elephant Conservation Act.

Eventually, in 1993, he and Oria founded Save the Elephants, an organisation intended to do just that. And in some places it has worked. First in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, and later in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, populations have risen. Even Angola and Zimbabwe are showing signs of things picking up.

Success, then. But qualified. For the poachers have moved on to fresh pastures—or, rather, forests. Africa’s forest elephants, recognised by conservationists as a species separate from savannah elephants since 2021, are now the animals most in the cross-hairs. In the 31 years previous to their recognition their population is reckoned to have fallen by 86%, and it is still heading south. By comparison, savannah elephants were down 60% in 50 years: horrible, but not quite as bad.

Between the two species, about 400,000 African elephants remain. The research side of Save the Elephants, operating from its base in Samburu National Reserve, currently keeps tabs on 1,000 of them, sometimes still using field glasses, notebooks and the trusty Cessna, but these days also courtesy of satellite-monitored radio collars.

And the bees? As of last year, more than 14,000 hives had been deployed by farmers in Africa and Asia eager to render themselves elephant-free.