Astronomers have just captured something extraordinary: the first-ever map of a supernova’s shape. Using data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, they discovered that the first moments of a star’s explosion aren’t perfectly round at all—but stretched and uneven.

On April 10, 2024, the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) spotted the first burst of light from a massive dying star, 12 to 15 times heavier than our Sun. Within just 26 hours, astronomers swung the VLT toward the event to seize a once-in-a-lifetime look at the opening act of a stellar death.

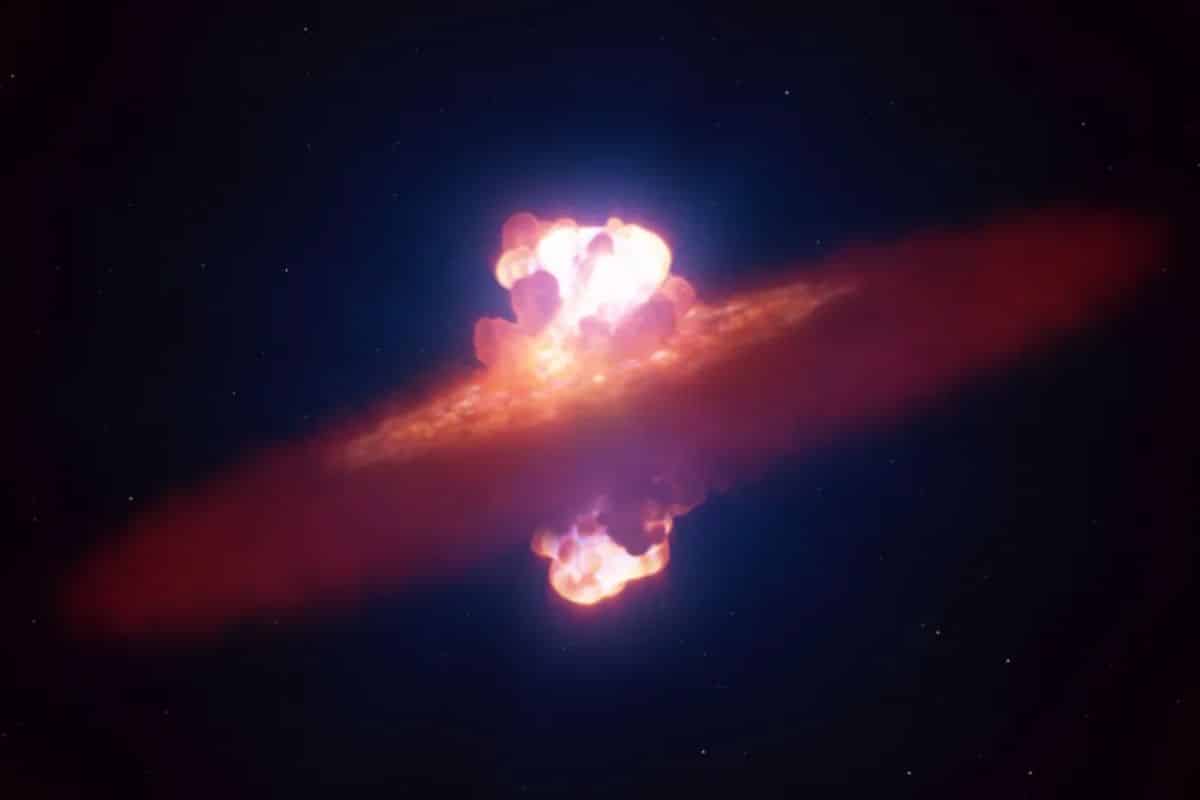

The spectacular image—an artist’s rendering—is based on real VLT data. It shows how, through quick observation, researchers managed to glimpse the explosion’s shape in its very first moments. Had they waited even one more day, this stage would have vanished from view.

Known as SN 2024ggi, the blast occurred in the spiral galaxy NGC 3621, roughly 22 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra. A VLT image from April 11 pinpoints the exact location of the explosion within that distant galaxy.

What happens when a star dies

A massive star stays almost perfectly round because of a fragile balance between the inward pull of gravity and the outward force of nuclear radiation created by fusion at its core. When that balance fails, gravity wins. The star’s core collapses, pulling its outer layers inward until they rebound, sending a colossal shock wave racing outward.

When that shock wave bursts through the surface, it releases an enormous amount of energy—lighting up space in a spectacular display we call a supernova. Yet how that shock actually forms and spreads has long puzzled scientists.

For a few fleeting hours after the blast, before the debris interacts with its surroundings, astronomers can catch a glimpse of the supernova’s original shape. Using a sophisticated technique called spectropolarimetry—which splits light by wavelength and measures the vibration direction of waves—VLT scientists captured that shape for the first time.

An olive-shaped explosion

Data from the VLT’s FORS2 instrument—the only tool in the Southern Hemisphere capable of such a feat—revealed that the first light of the explosion wasn’t emitted evenly in every direction. Instead, it was stretched along one axis, resembling an olive rather than a sphere.

As the supernova expanded, its light began to show how the blast was colliding with the surrounding gas. By the tenth day, the star’s hydrogen-rich outer layers became visible—and surprisingly, they were aligned with the same axis as that initial shock. That consistency means the explosion’s core was directional from the very beginning, hinting at a deeper physical mechanism behind its symmetry.

This breakthrough view challenges some long-standing supernova models and strengthens others, bringing astronomers closer to understanding how massive stars end their lives in such breathtaking catastrophes.