Summary

Our survey of 1000+ New Zealanders found that more people support increasing investment in urban cycleways than oppose it (41% vs 35%), but that 24% were “neutral”. Results indicate significantly higher support amongst younger people, Māori, and those in the highest income bracket.

Support was politically polarised, with significantly higher support from NZ First and centre-left voters (Labour, Te Pāti Māori and the Green Party). Advocates for cycleways may need to do more to inform the public of their benefits: (1) safety and population health (physical and mental); (2) improved access to low-cost mobility; (3) reduced greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution (air and noise pollution); and (4) favourable economic benefits on cost-benefit analyses. But there is also a need to ensure that any new cycleways have extensive public consultation, good design and involve sharing the benefits of change broadly.

Urban cycleways deliver well-documented gains to safety and population health, as well as environmental benefits and economic benefits to regions (see Box 1). For such reasons, cities around the world are increasingly expanding cycleway networks and bike-share schemes, with success stories in North America (eg, Montreal) and in European cities (eg, London, Paris, Amsterdam and Copenhagen).1 Some also argue that this shift to cycling may reduce traffic congestion,1 and so there may also be benefits for car drivers. Nevertheless, there can be public opposition for a range of reasons, including cost to constrained city budgets, the disruption during construction, and how removing curb-side parking or loading bays might impose problems on small retailers, tradies, and mobility-impaired drivers.

Box 1: Overview of health, societal, environmental and economic benefits of cycleways (full details with references in Appendix 1)

Improved safety and population health: Separated cycleways lower crash risk compared with mixed-traffic routes, and shifting trips from cars to bikes reduces injury risk to others (given fewer vehicle kilometres travelled).

Equity and mobility justice benefits: High-quality cycle networks provide low-cost mobility for short urban trips, expanding access to jobs, education and services.

Environmental co-benefits: Transport mode shift to cycling cuts greenhouse gas emissions and local air and noise pollution.

Economic benefits (health cost savings): Across NZ and international studies, investments that promote active transport consistently deliver health and productivity benefits that far outweigh their costs, often by large margins.

Economic benefits (tourism): Urban cycleways can link urban areas and airports to regional cycle trails with this benefiting both local and international tourism.

Economic benefits (local businesses): Evidence from North America and NZ shows that high-quality walking and cycling infrastructure supports the economic viability of local shopping areas while also reducing household transport costs and keeping more income within local economies.

Economic benefits (housing values): There is evidence that increasing cycleway density may increase property values, according to a study of Christchurch properties.

What our survey on attitudes to cycleways found

Our 2024 survey of more than 1000 people was designed to reflect the national NZ population. The questions covered a range of population health issues, including one question measuring support for investing more in cycleways in urban areas. The full details on the methodology of the survey and weighting were recently published in the journal Risk Analysis.2

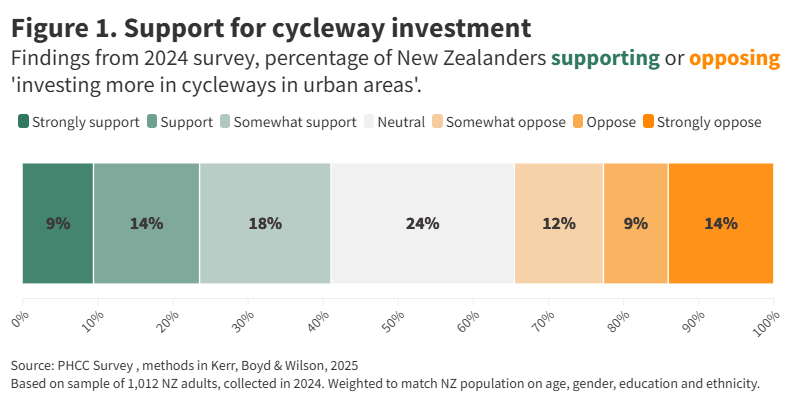

Figure 1 shows that more of the NZ public support increasing investment in urban cycleways than oppose this (41% vs 35%), but that 24% were “neutral”. These results can be compared with NZTA Waka Kotahi survey results showing 68% of urban New Zealanders support cycling in the community (a fairly stable result in recent annual surveys).3 Similarly, cyclists receive social support to cycle, with 59% encouraged by family and 41% by friends.3

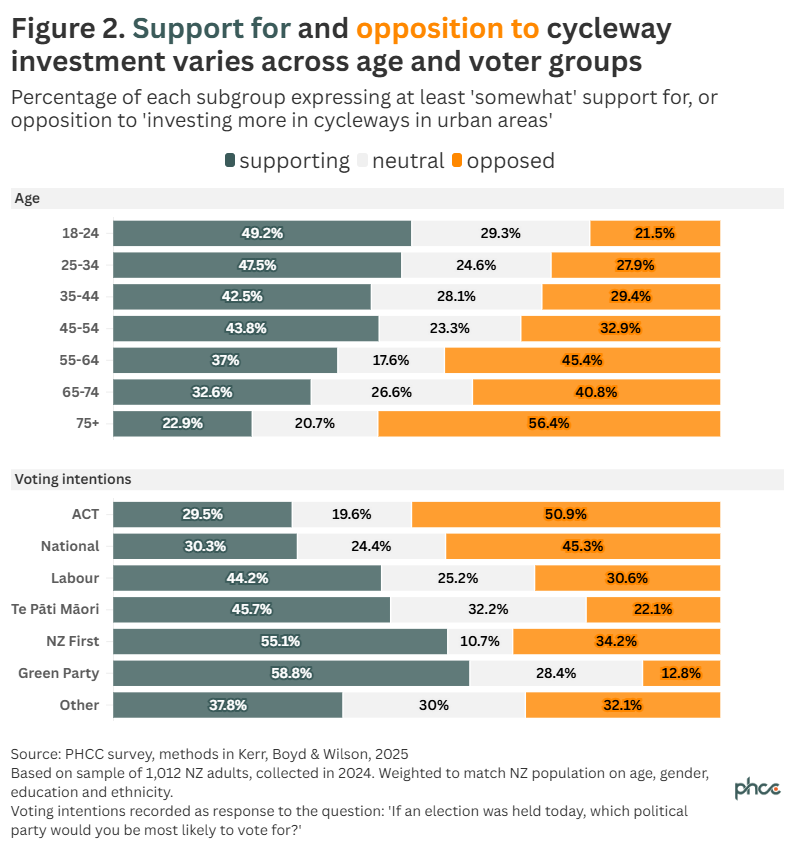

In our survey, some groups were more likely to support cycleways than others. For example, there was a clear trend for age, with greater support among young people and more opposition among older age groups (Figure 2). There was also marked variation in support by voting intentions, with significantly higher levels amongst NZ First supporters and those of centre-left parties (Labour, Te Pāti Māori and the Green Party) compared to National and the ACT Party supporters (Figure 2).

We conducted additional regression-based analyses (controlling for the fact that some demographic factors are related, eg, age and income). Results indicated significantly higher support amongst Māori and people in the “Other” ethnic grouping (compared to Pākehā), and amongst those in the highest income bracket. There was also significantly higher support amongst people who were more trusting of the media and politicians as information sources (see Appendix 2).

Implications for active transportation advocates and government officials

These survey results seem to indicate that if the benefits of urban cycleways (see Box 1) are to be fully realised, then higher support levels by the NZ public may be needed. This suggests a need to both address public concerns around perceived downsides of cycleways and to clarify any misconceptions.4

To better understand the reasons for opposition, more in-depth locality-based research should be undertaken (eg, in-depth surveys, focus groups and media discourse analysis). Opposition often comes from a vocal minority, leading people to perceive opposition is more widespread than it might actually be. Taking multiple perspectives into account as part of early, open and extensive consultation from trusted sources is likely to create stronger community support.5

It could be helpful to explore if opposition is partly connected to the cost of Council rates/rate rises, which was an important public concern during the 2025 local government elections. NZ mayors have described the funding model for local government as being “broken”.6 As such, central government could better support local government with revenue (eg, allow regional fuel taxes etc) and could directly support cycleway expansion. The latter is potentially justified in terms of the national goal of reducing climate-heating emissions and the national benefit of international tourists coming to use NZ’s recreational cycling trails.

Nevertheless, it is important that constructive actions are taken to maximise public support when any new cycleway development is considered. Potential actions include: (i) extensive community consultation on the plans (see the case study in Box 2); (ii) prioritising links to schools and workplaces etc (to broaden support); (iii) mitigating impacts on business where feasible; (iv) considering time-limited trials (with clear success criteria and willingness to adjust or remove elements that don’t work); (v) avoiding gaps so routes feel safe end-to-end (since isolated segments can underperform and feed “empty lane” narratives); and (vi) “bundle the benefits” by pairing new cycleways with improving public transport services and safer pedestrian walkways and crossings etc. Such consultation, good design and sharing the benefits of change broadly, could all facilitate the successful expansion of urban cycling networks.

Box 2: Cycling Infrastructure Case Study: New Plymouth

Regional cycle trails are already known to be highly popular and economically valuable in Aotearoa New Zealand. The coastal shared pathway in Ngāmotu, New Plymouth illustrates how even smaller, local cycling infrastructure can be transformative: through visionary planning, strong community engagement, and partnership with Māori, the city reoriented itself toward its coastline, creating a 13.2 km pathway. The award-winning pathway is now widely used and economically beneficial, with high daily cycling counts, strong tourism appeal, and positive health-economic returns.

A detailed overview of the New Plymouth coastal shared pathway success is provided in Appendix 3.

Yet despite these successes, a proposed 9.7 km extension to Waitara has reignited debate about costs and ratepayer burden, showing that public support for cycleway expansion is not assured even in places with clear past benefits.

What is new in this Briefing?Our survey of over 1000 New Zealanders found that more of them support increasing investment in urban cycleways than oppose (41% vs 35%), but that 24% were “neutral”.There was significantly higher support amongst younger people, Māori, those in the “Other” ethnic grouping, and those in the highest income bracket. Support was also markedly influenced by voting intention with significantly higher support from centre-left voters. Implications for policy and practiceMore in-depth locality-based research is desirable to understand why some people are unsure or opposed to investment in urban cycleways.If active transport advocates and local government officials wish to continue to increase investment in cycleways, then they may need to do more to inform the public of the benefits: (1) safety and population health (physical and mental); (2) improved access to low-cost mobility; (3) reduced greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution (air and noise pollution); and (4) economic benefits (health cost savings, tourism benefits, increased property values, enhanced regional economies, etc).It is also important to ensure that any new cycleways have extensive public consultation with consideration of all perspectives, good design and involve sharing the benefits of change broadly (with our case study of New Plymouth showing these).Central government could better support local government with revenue raising (eg, allow regional fuel taxes etc) that could go towards cycleway expansion. Or central government could directly contribute to urban cycleway development (eg, given national benefits in addressing climate change).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Liz Beck for her invaluable assistance that allowed us to write a case study on the successful New Plymouth Coastal Walkway.

Authors details

Prof Nick Wilson, Co-Director, Public Health Communication Centre, and Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka, Pōneke | University of Otago, Wellington

Dr Jonathan Jarman, retired Medical Officer of Health of 28 years and currently a student with the Department of Science Communication, University of Otago.

Dr John Kerr, Public Health Communication Centre and, Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka Whakaihu Waka, Pōneke | University of Otago, Wellington

Appendix 1: Summary of the health, societal, environmental and economic benefits of cycleways Improved safety and population health: Separated cycleways lower crash risk compared with mixed-traffic routes,7 and shifting trips from cars to bikes reduces injury risk to others (given fewer vehicle kilometres travelled). More people cycle when protected lanes are built,8 and increases in physical activity from cycling have wide ranging health benefits. These include reducing all-cause risk of death,9 with NZ evidence for this as well.10Equity and mobility justice benefits: High-quality cycle networks provide low-cost mobility for short urban trips, expanding access to jobs, education and services.11 For example, Māori cycle at similar rates to Pākehā but are more likely to do so because of economic necessity. The factors identified as most likely to encourage more cycling for Māori are more cycle lanes and bicycle paths, and infrastructure that enables social cycling.12 Health equity benefits can also arise (see next paragraph).Environmental co-benefits: Transport mode shift to cycling cuts greenhouse gas emissions and local air and noise pollution.11 See also this study of a programme in two NZ cities13 and a modelling study for NZ which found that decarbonising transport (which included increasing cycling) “might improve overall population health, save the health system money, and reduce health inequities between Māori and non-Māori.”14Economic benefits (health cost savings): The two NZ cities programme (mentioned above) that covered cycleways and walkways had benefits that outweighed costs at 11:1 (mainly in terms of the health benefits).15 A modelling study of a mixed intervention (including reduced driving, increased cycling and use of public transport, and light vehicle electrification) also reported health system cost savings.14 Similarly, NZ research has estimated the potential productivity gains from preventing a wide-range of chronic diseases16 – with many of these diseases being prevented via increased physical activity. Internationally, city-scale analyses in Europe show favourable benefit-cost ratios as cycle networks expand.9Economic benefits (tourism): Urban cycleways can link urban areas and airports to regional cycle trails with this benefiting both local and international tourism. The tourism spend of Great Ride users is ~NZ$1 billion annually and an estimated 18% of Great Ride users are international visitors.17 Examples of these linkages include the Lower/Upper Hutt cities connecting with the Remutaka Cycle Trail; Napier and Hastings connecting with Hawke’s Bay Trails; Nelson connecting with Tasman’s Great Taste Trail; and Hamiton connecting to the Waikato River Trails. Some such urban infrastructure might become tourism attractions in themselves eg, the award-winning New Plymouth Coastal Walkway (for walkers, runners, cyclists and skaters)18 (see the case study in Box 2). The main aims of Ngā Haerenga New Zealand Cycle Trails are to create jobs, create a high-quality tourism asset, provide ongoing economic opportunities for regions, and provide a range of recreational and health benefits for New Zealanders.19Economic benefits (local businesses): A review of 23 studies in the United States and Canada found that creating or improving pedestrian and cycling infrastructure had positive or non-significant economic impacts on most retail and food service businesses.20 A study of nine shopping areas in Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington concluded that pedestrians and cyclists contribute a higher economic spend proportionately to the modal share and are important to the economic viability of local shopping areas. The study also identified that retailers generally overestimate the importance of on-street parking outside shops. Shoppers valued high-quality pedestrian and urban design features in shopping areas more than they valued parking.21 Cycling infrastructure can reduce transport costs (lower fuel costs, no parking fees, and low running costs) which keeps more household income circulating in the regional economy.Economic benefits (housing values): A University of Canterbury study found that cycleway density increased property prices in Christchurch.22 This was around $1000 per property and the total value attributed to cycleways was $1.52 million of the 2024/25 rates collected by the Christchurch City.

Appendix 2: Linear regression analyses

Figure S1 below shows the results of a statistical analysis examining which factors are linked to people’s support for investing more in urban cycleways. Each data point in the figure represents the estimated effect of a characteristic (such as age, education, income, or political views) on support for cycleway investment, after taking all other factors into account. The horizontal lines show the uncertainty around those estimates (at the 95% level), with blue dots indicating relationships that are statistically significant. Where a subgroup is labelled “(ref)”, this is the “reference group” against which all other subgroups in the category are compared.

Overall, the figure helps to illustrate which social and political factors are most strongly associated with support for improving cycling infrastructure.

Figure S1: The relationship between socio-demographic factors and level of support for investing more in urban cycleways in NZ (linear regression model)

Appendix 3: Detailed case study of cycling infrastructure in New Plymouth

There is compelling evidence that regional cycle trails are popular in Aotearoa New Zealand (see Box 1 on the tourism spend of Great Ride users of ~NZ$1 billion annually). But what about smaller localised cycling pathways? In this case study we will look at the coastal shared pathway in Ngāmotu New Plymouth. Currently the shared pathway extends from the Port to the beach at Bell Block and is 13.2 kilometres long. Through inspirational planning, extensive community consultation, and partnership with Māori it has changed the way a city sees itself.

“It’s the first walkway of its kind where a city has invested in a serious piece of amenity-driven infrastructure that has delivered a “city-changing” outcome” (Dave Irwin).23

Ngāmotu New Plymouth is a city located on the wild west coast of Te Ika-a-Māui North Island. Designed in the 19th century, the town largely turned its back on the port and coastline with shops and buildings designed around the main street of the town.24 Between the main street and the coast were industrial buildings and the railway yards. The railway station closed in 1989 when the railway yards were relocated out of the city centre.25

Visionaries in the New Plymouth District Council saw an opportunity and commissioned a plan named “Mountain to the Sea” in 1995 to celebrate the coastline rather than hide from it.26 There was controversy at the time. Some ratepayers and councillors questioned whether the proposed projects were a good use of public money. Early stages were estimated to cost millions of dollars. Supporters saw it as a bold vision to reconnect the city to its coast while critics called it an unrealistic urban design project for a small regional city. Nevertheless, the pathway from Ngāmotu Beach to Waiwhakaiho River was completed in 2001.27 It quickly became very popular and later won national landscape architecture and planning awards.26

An economic evaluation in 2015 looking at the health benefits for users and costs of the coastal pathway concluded that the benefits for walkers and cyclists far outweighed the cost. It was concluded that the coastal pathway was a very successful infrastructure investment even though the implementation costs had been high. It is used for active commuting as well as recreation and other utility trips.28

Currently a daily average of 468 people cycle on the Fitzroy part of the pathway on weekdays and a daily average of 647 during the weekend. Numbers are higher during the summer months.29 Many businesses are likely to benefit from cyclists using the shared pathway. For example, there are four cafés located directly on the pathway. Many hotels and motels offer free bike hire as well as private businesses with bike rentals. Tripadvisor lists the coastal path as the second-best tourist attraction in New Plymouth with a rating of 4.8 out of five.30

“It’s put us on the map, to be honest. It’s now the jewel in the visitor’s crown. When people come to New Plymouth, the one thing they do is the coastal walkway and there’s massive community ownership of it” (Richard Bain).23

But controversy has returned to the New Plymouth Coastal Walkway – at least in terms of its extension. Project partners Manukorihi Hapū, Otaraua Hapū, Pukerangiora Hapū, Puketapu Hapū, and the New Plymouth District Council have designed a 9.7 km extension to the Coastal Walkway to Waitara. This would make the entire coastal path almost 23 km long and would provide a safe off-road shared pathway between the two centres, including passing significant cultural sites with interpretive elements telling the stories of tangata whenua.31 The budget is $42.4 million which includes a $18 million contribution from NZTA Waka Kotahi.32 Concerns have been raised about value for money and the burden on the ratepayers.33 As such, this case study shows that even with a marked history of local success, full public support for cycleway extension is not necessarily guaranteed.