Autism is a lifelong condition impacting how individuals process information and interact with the world, simultaneously protected as a disability and recognized as a form of neurodivergence. Autism affects how people think, feel and communicate with others. The term autistic is typically applied to individuals who are unified by certain criteria (for example, sensory sensitivity, intense personal interests and struggles with ‘normative’ expectations of social communication). However, it is widely accepted that autistic people are each unique and may possess a heterogeneous assemblage of co-morbidities that impact their daily lives (for example, ADHD, depression). Owing to non-disclosure and lengthy diagnosis waiting times, the true number of autistic people is unknown. Nevertheless, even the most frequently reported estimate of 1% of the population (generally accepted as an underestimate) equates to 700,000 people in the UK, and recent research suggests that, in England, this figure may actually be up to 3%7.

Autistic people are particularly under-represented in higher education, where barriers such as difficulties with social interaction and associated stigma hinder their success, and lead to rates of disclosing autism that are 50 times lower than the general public8. Furthermore, autistic individuals are potentially ten times more likely to withdraw from education prematurely9, despite many frequently cited ‘autistic traits’ having no apparent impact on success in academia10. Historically, higher education research studies exploring autistic experiences on a large scale have been uncommon. In recent years, there has been a push in higher education to better recognize and accommodate the needs of autistic people, particularly as numbers of autistic people entering higher education increases11. This is notable amongst published pedagogic studies that challenge the medical model of autism, in which autistic people are considered to be lacking and in need of a cure. Instead, the social model, which identifies wider social determinants as creating exclusions and disability, rather than an individual’s biological or neurological diversity, is increasingly applied.

Despite inclusion studies focusing on autism in the wider social context, it remains comparatively under-discussed in geosciences, where efforts to enhance inclusion of disabled individuals have focused primarily on physical, sensory and mental-health-related disabilities12 — understandable given the prevalence of field-based and practical activities. Nevertheless, there remains significant scope to improve recruitment, support and retention of autistic people in geosciences through innovations that benefit the wider population as well as the target group. UK Higher Education Statistics Agency data show that over the last ten years geosciences recruited an above average percentage of students who disclose a disability, suggesting that autistic individuals may also be above average in geoscience (particularly in light of non-disclosure), and yet, the number of studies aimed at informing and developing support for autistic learners in geosciences is comparatively low8,12,13,14,15.

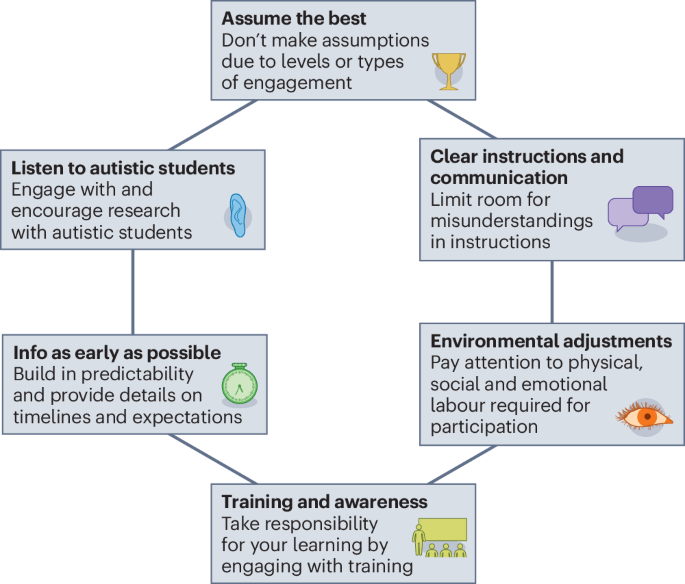

Collaborative research that co-creates with, and gives a voice to, autistic students is clearly vital to fully inform design and implementation of inclusive interventions. Equally important, but more neglected, is how we listen to these voices, and how we respond to them. We argue that all who work and study at universities (and beyond) are responsible for fostering a safe, friendly and inclusive environment. All university staff and students need to appreciate the experiences of neurodivergent people and how we can work collaboratively to improve inclusion and access.