The cosmos is so full of mysteries that sometimes, astronomers will find answers to things you’ve probably never even heard of. Take, for instance, the luminous fast blue optical transients—LFBOTs for short—those weird, fading flashes of blue and ultraviolet light whose source has long eluded astronomers. Well, astronomers may finally have an answer.

LFBOTs are relatively rare events. They’re so bright that they’re visible over hundreds of millions to billions of light-years. But they only last for a few days. Astronomers saw one for the first time in 2014 but have found only about a dozen since. Last year, astronomers led by the University of California (UC), Berkeley, spotted AT 2024wpp, the brightest LFBOT seen to date. A close investigation of this lucky signal seems to suggest that the blue flashes are remnants of a hungry, supermassive black hole ripping apart its companion star.

Two papers on the analysis, led by Natalie LeBaron and Nayana A. J., a graduate student and a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, respectively, have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and are currently available on arXiv.

“AT 2024wpp belongs to this unique class of transients powered by a central engine with extreme luminosities and time scales,” Nayana A. J. told Gizmodo in an email. “More broadly, this event shows how cosmic explosions of this kind can reveal invisible black holes and extreme physics.”

A mystery in blue

The rarity of LFBOTs made it difficult to determine their origin. Astronomers had some guesses, like weird supernovas or a black hole gobbling up cosmic gas, but the data wasn’t the best match for such scenarios. So when the team noticed how ridiculously bright AT 2024wpp was, investigations began instantaneously.

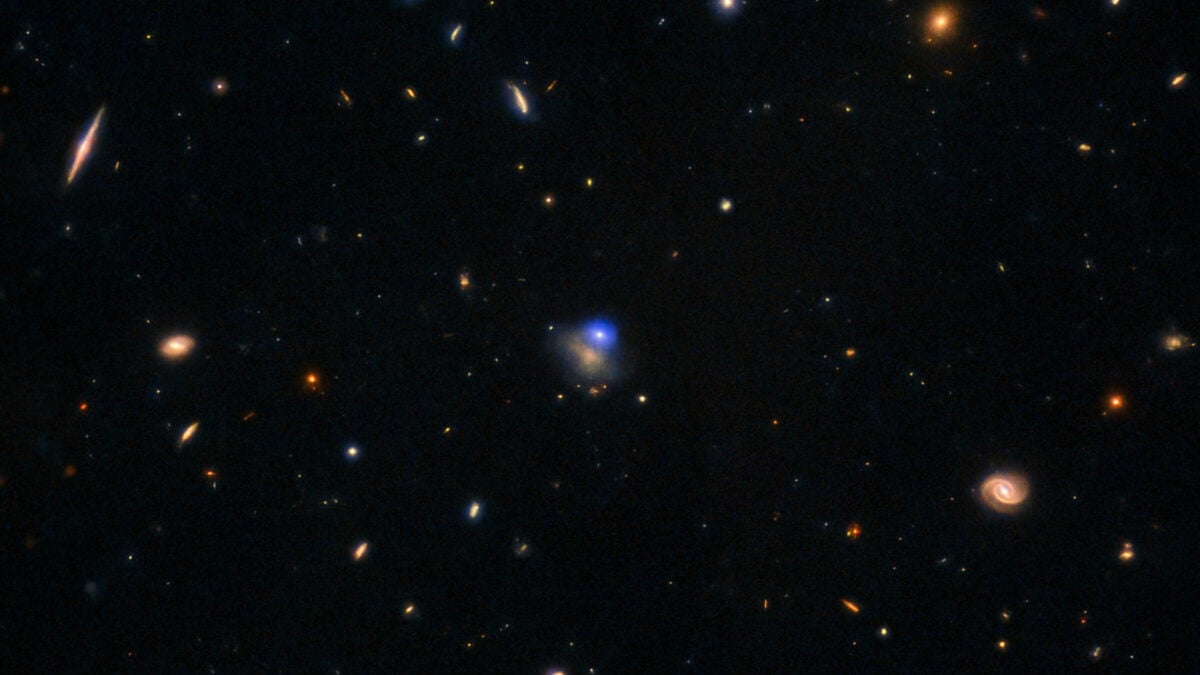

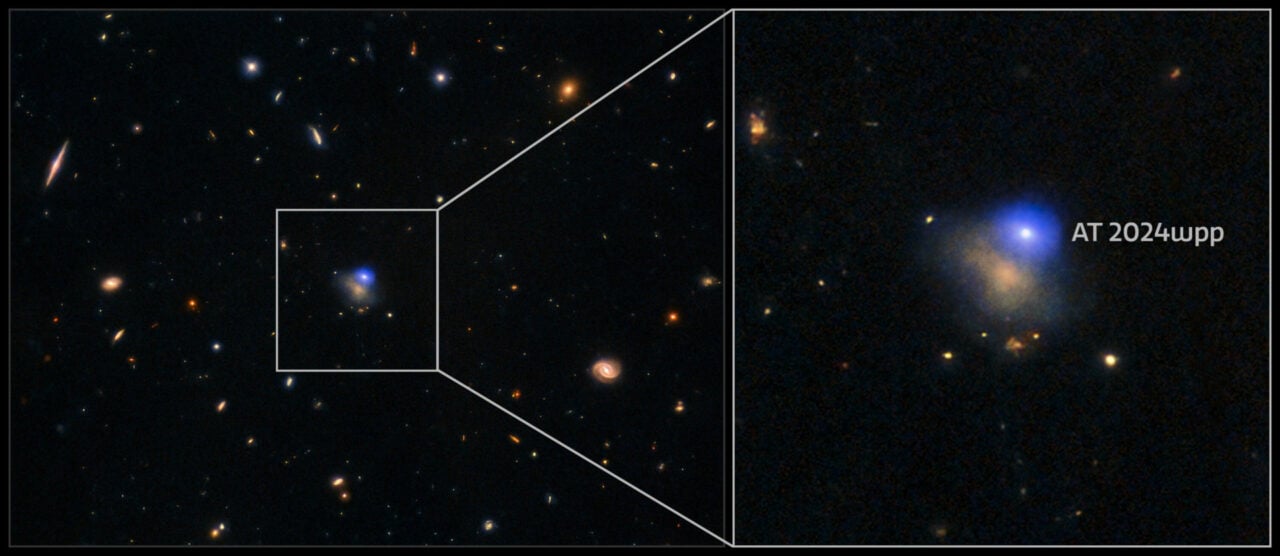

This composite image features X-ray, ultraviolet, optical, and near-infrared data of the luminous fast blue optical transient (LFBOT) named AT 2024wpp. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA/NASA/ESA/Hubble/Swift/CXC/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

This composite image features X-ray, ultraviolet, optical, and near-infrared data of the luminous fast blue optical transient (LFBOT) named AT 2024wpp. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA/NASA/ESA/Hubble/Swift/CXC/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

“It was immediately clear that this was not an ordinary event,” recalled Nayana A.J. “The brightness, the color, and how quickly it evolved made it stand out right away. What could possibly produce something this extreme?”

“Typically, LFBOTs are discovered at distances too far for datasets that are this extensive and detailed to be obtained,” added LeBaron, also in an email to Gizmodo. But because AT 2024wpp was so bright, the team had the rare chance to carry out follow-up observations over several months, she added.

And it literally took everything that astronomers had; the initial analysis alone harnessed three X-ray telescopes, three radio telescopes, and three ground-based telescopes to measure the signal at all possible wavelengths. Then, Nayana A.J. and LeBaron each led analysis teams to pick apart the data.

The weirdest of them all

From their investigations, the researchers hypothesize that LFBOTs come from powerful tidal disruption events preceded by a “parasitic” black hole binary system, according to a university statement. At the very least, looking at AT 2024wpp confirms that these transients “require some sort of central energy source beyond what a supernova can produce normally on its own,” LeBaron explained.

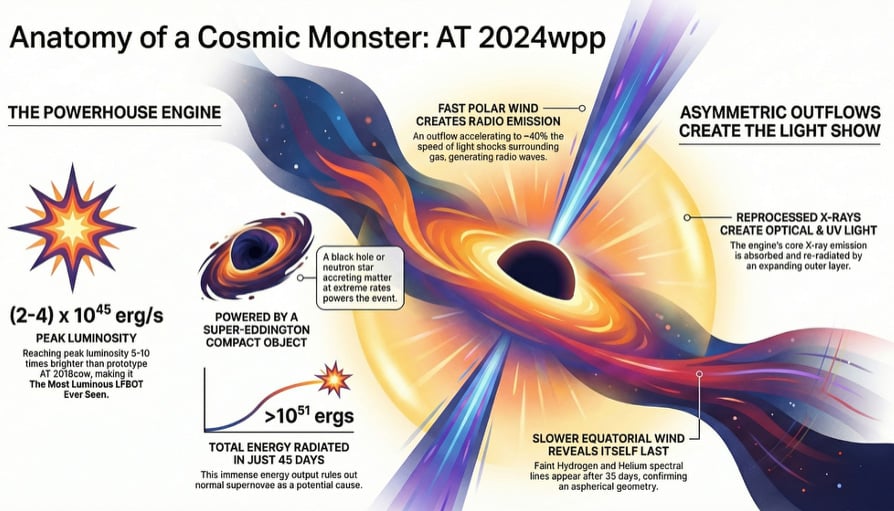

An infographic explains how an intense tidal disruption event gave rise to AT 2024wpp. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC Berkeley

An infographic explains how an intense tidal disruption event gave rise to AT 2024wpp. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC Berkeley

In this scenario, a massive black hole more than 100 times the mass of our Sun gradually siphons stellar material from its companion star. Eventually, the star floats a little too close to the black hole, and the poor object is torn apart into a rotating disk of debris. Finally, collisions between the stellar debris and gas swirling around the black hole produce jets of X-ray, ultraviolet, and blue light—a luminous fast blue optical transient.

Tidal disruption events themselves are uncommon, but the ones that cause LFBOTs should be even weirder, as “AT 2024wpp evolves on much shorter timescales, allowing us to probe black holes in a mass range that bridges stellar-mass and supermassive black holes,” Nayana A.J. added.

Full of surprises

For astronomy at large, the new analysis has several important implications. It’s a stellar demonstration of how the many capable telescopes around the world (and in space) can quickly coordinate to piece together a “much more complete picture” of mysterious cosmic signals, Nayana A.J. explained.

Importantly, studying what comes from a black hole provides critical clues as to the physics inside and around a black hole, the researchers added. And with the next generation of telescopes—including the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Telescope, when it’s not looking into the void—humanity’s knowledge of the universe is for certain slated to grow richer.