It was Vanity Fair magazine that dubbed Robert Stern, who has died aged 86, “the king of Central Park West”, following the phenomenal success of his 2008 condominium at 15 Central Park West. Conceived as a homage to the grand and gracious Upper East Side apartment blocks so beloved of old money, it was a calculated retort to the anomie of New York’s modern glass towers.

Like its 1920s predecessors, it was clad in creamy limestone (85,000 pieces of it) and while this added a couple of million dollars to the budget, it turned out to be a mere bagatelle. The luxurious apartments were eagerly snapped up by the new money of hedge fund managers and celebrities, including Sting and Denzel Washington. Total sales of around $2bn made “15 CPW” the most commercially successful apartment building in the world at the time. Its developers, Arthur and William Lie Zeckendorf, scions of an American real estate dynasty, effectively recouped the cost of the limestone from the sale of a single apartment.

The Central Park skyline of New York, with 15 Central Park West the creamy limestone-clad building to the right of centre.

Photograph: P Batchelder/Alamy

Stern’s forte was to persuade his clients to look backwards, not forwards, with soothing and slickly executed pastiches of historical styles. “Many modernist works of our time tend to be self-important objects, and that’s a real quarrel that I have,” he told the New York Times in 2007. “Buildings can be icons or objects, but they still have to engage with the larger whole.”

His timing was apt, as his early career coincided with a general disillusionment with modernism and a shift into the impish historicism of postmodernism. But he soon discarded impishness, and his ponderous oeuvre of lushly appointed historical throwbacks was catnip to conservative critics and clients. It was even given the stamp of approval by George W Bush, for whom Stern designed a presidential library in Dallas in 2013.

Buildings can be icons or objects, but they still have to engage with the larger whole

Other key projects included the Museum of the American Revolution and the 58-storey Comcast Centre skyscraper, both in Philadelphia. Two residential colleges at Yale University were executed in fussy “collegiate Gothic”, all turrets, bay windows and campaniles, which made them look as though they had been there from time immemorial.

A doggedly productive architect, scholar and educator, Stern combined running a 300-strong architectural practice with his role as dean of the Yale School of Architecture from 1998 to 2016. He also wrote a series of lavish, encyclopedic volumes on the architecture of New York. Like many of his generation, he eschewed computers and always drew by hand.

The George W Bush presidential library and museum, in Dallas, Texas, 2013. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

Compared with what he saw as modernism’s alienating abstraction, Stern claimed that his buildings delivered experiential uplift through the atmosphere conjured by legible historical precedents. His 2006 library for Bronx Community College alludes to Henri Labrouste’s 19th-century Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, not only to acknowledge a historical model, but also because Stern wanted Bronx students to luxuriate in Parisian grandeur. “My interest is not in being an autobiographical architect but a portraitist of places,” he once declared. “Other architects put the same building, more or less, in many different locations.”

Born in Brooklyn, Robert was the elder son of Sonya (nee Cohen) and Sidney Stern. His father sold insurance, ran a hardware store and drove a cab, while his mother worked at the B Altman & Co department store in midtown Manhattan.

Educated at the Manual Training high school in Brooklyn, Robert excelled in Latin, geometry and trigonometry, and also had a penchant for drama. In his youth, he went on long, ruminative walks around Manhattan, studying its architecture. “I became an architect because I loved the buildings of my city, New York, and imagined one day that I would make ones like them,” he wrote.

A doorman outside 15 Central Park West in New York – it was clad in 85,000 pieces of limestone that added millions of dollars to the budget. Photograph: Richard Levine/Alamy

At that time, Columbia University had no undergraduate architecture programme, so he majored in history, going on to earn a master’s degree in architecture at Yale in 1965. After a year as a curator at the Architectural League of New York, a job finessed through Philip Johnson, his great mentor, he went to work for Richard Meier, one of the influential “New York Five”. He then spent more than two years in the city’s housing department before establishing Stern & Hagmann with John Hagmann, a fellow student from his days at Yale. In 1977 he founded its successor firm, Robert AM Stern Architects, now known as RAMSA.

Many of Stern’s early projects were private houses for affluent clients in the Hamptons and elsewhere, a seam of work that rumbled agreeably along throughout his career. Commercial commissions included the 1993 Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, designed as a playfully engorged version of a clapboard suburban house, and large scale developments for Walt Disney World in Florida, including the picturesque Yacht Club and Beach Club resorts. He also devised the masterplan for Celebration, Disney’s nostalgic re-envisaging of small town America.

In 2011, Stern was honoured with the Driehaus prize, for achievements in contemporary classical architecture, established in 2003 as an alternative to the modernist Pritzker.

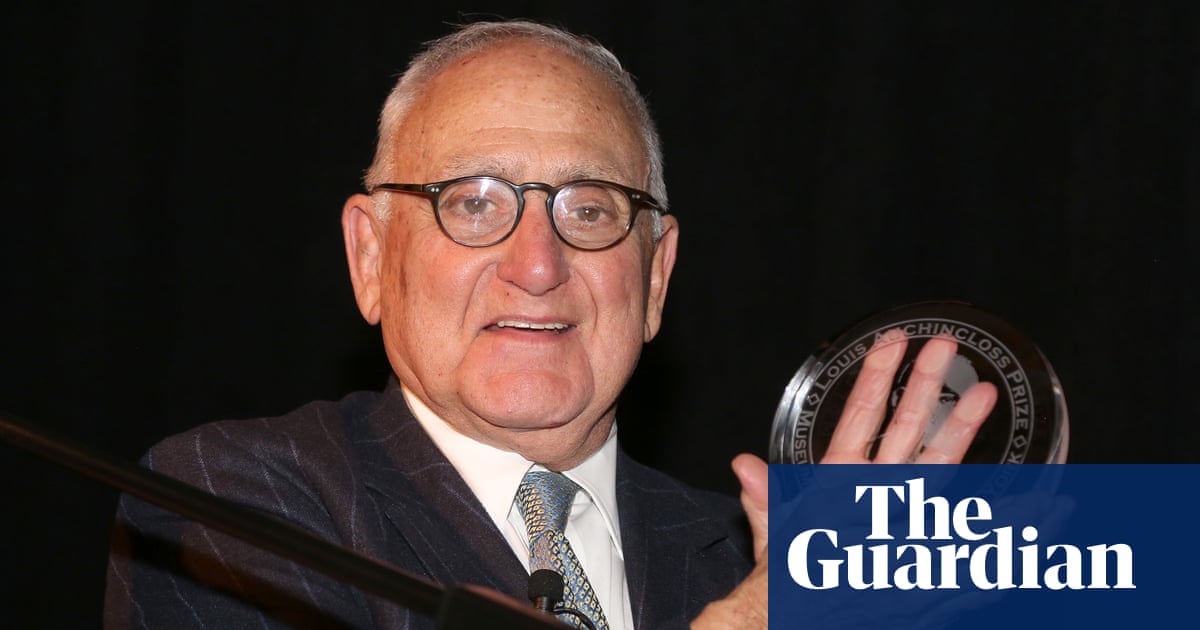

A sartorial dandy with a waspish wit, Stern favoured tailored pinstripe suits and enjoyed vodka martinis. In 1966, he married Lynn Solinger, a fine arts photographer; they divorced in 1977. Along with their son, Nicholas, he is survived by his brother, Elliot, and three grandchildren.

Robert Arthur Morton Stern, architect, born 23 May 1939; died 27 November 2025