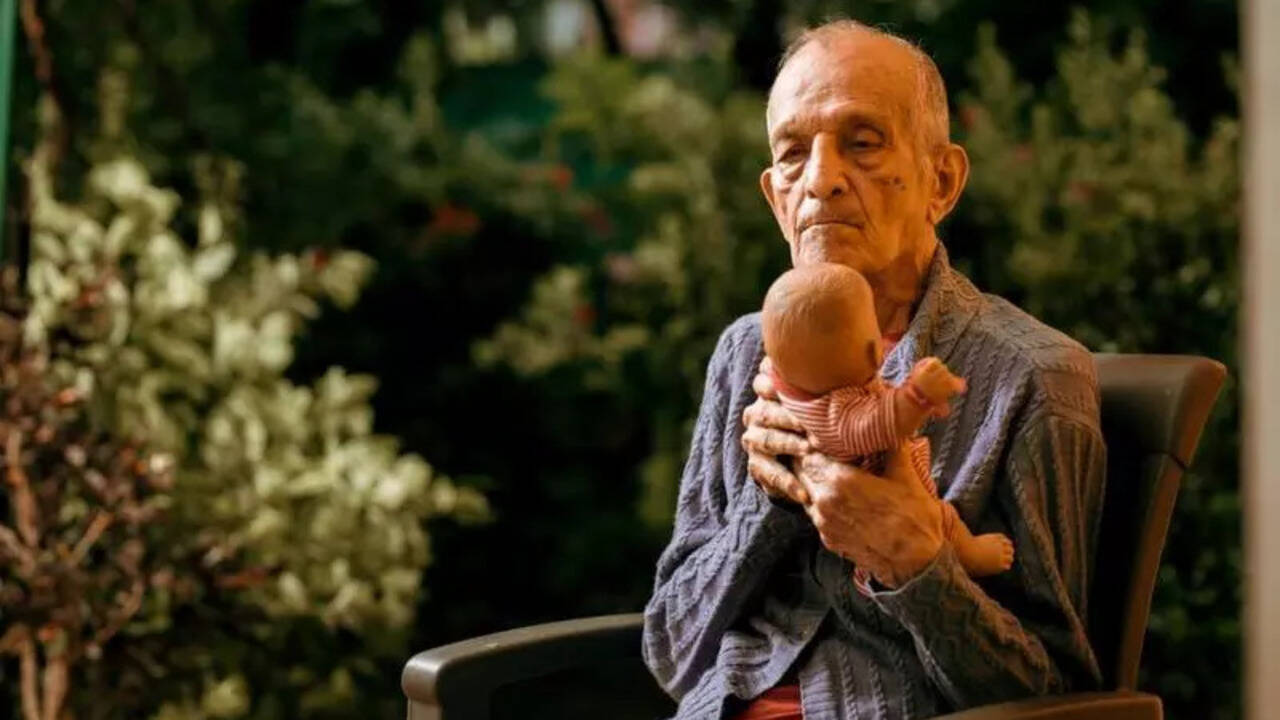

In a Colaba apartment, Khurshid Mehta, 58, sits beside her 89-year-old mother, checking her overgrown nails and asking the caregiver to trim them later. Her mother, frail in a red-and-black wheelchair, turns plastic spinning tops in her hands and nudges a wheeled dinosaur toy; a soft red octopus rests beside her.

Mehta lifts a glass bowl half-filled with thick mango juice and brings a spoonful to her mother’s lips. “She finds it very difficult to swallow, especially liquids. That frightens me the most,” Mehta says. “I never want her to reach a stage where she needs a feeding tube.” This difficulty, known as dysphagia, is a common and serious symptom as dementia progresses. Neurologist Shirish Hastak explains, “People with dementia lose control over certain areas of the brain that regulate behaviour.”

The scale of the challenge was highlighted by a recent Lancet Psychiatry study by researchers at the Indian Institute of Science, which called for a national dementia policy. The authors argue that care must move beyond isolated treatment and be integrated into geriatric and mental health services, shaped by India’s social and economic realities. Dementia affects an estimated 8.8 million Indians today and is expected to cross 30 million by 2050. And yet, as Hastak notes, “Dementia is often misunderstood, it is more than just a memory problem, and it is not a normal part of ageing.” He describes it as a syndrome, a collection of symptoms rather than a single disease.

When words don’t come easy

Dementia usually begins later in life, often after 65. Mehta remembers her mother’s razor-sharp memory. “I would call her every morning and list out my tasks for the day. If I forgot something later, I would call her back, and she would remind me exactly what I had to do.” Gradually, her mother began forgetting things, resisting instructions, and arguing over small matters. Two falls in early 2021 worsened her condition. “After the falls, she stopped walking,” Mehta says. “Then she slowly began to speak gibberish.”

Prayer once structured her days. “She never missed a single prayer,” Mehta says. Now, her mother struggles to repeat even the simplest ones.

About six months ago, her mother grew aggressive. “She would pinch people to express her anguish,” Mehta says, adding that she does not blame her and sees it as distress rather than intent. The aggression has since stopped. Now, they often bargain with her like a child. Once health conscious and opposed to sweets, she will now trade a piece of chocolate for a sip of water. A caregiver wheels her around the compound, coaxing her to drink, which Mehta says is essential. Her mother has lived in the building for over forty years and is recognised by neighbours and security guards during these walks. She may not remember family names, but a sense of familiarity remains. Mehta says she feels some relief that her mother can no longer walk on her own, as people with dementia often wander off.

Risk of wandering

Take the case of Huseni Bhaiwala. “My father would often wander off,” recalls his daughter, Tara Karachiwala, 69. As his condition progressed, his behaviour became childlike and unpredictable; at times, he would wet himself unknowingly. Education mattered deeply to him. “He ensured his siblings and children received a proper education,” she says. He ran a hardware business and closed it in 1995, when he was about 75.

In his late eighties, Bhaiwala began experiencing hallucinations. “There were times when he would go out and not return for hours,” Tara says. He believed someone was trying to kill him and often forgot the way back. The family took precautions. “We made a band with his name and address, kept phone numbers in his pocket, and began locking the house,” she says.

Hastak explains, “This paranoia and loss of control stems from damage to the brain… confusion sets in, and this confusion can lead to hallucinations.”

Lost and found

In 2012, Bhaiwala became acutely restless. While Tara and her son Danish rushed to pick him up, a caregiver briefly unlocked the door to fetch her slippers. Bhaiwala noticed the opening and slipped out. By the time they realised, he was gone. The family searched through the night across markets, lanes, stations and hospitals. “A missing complaint was filed, but all the real work was done by us,” Tara says. Flyers were printed, newspaper ads placed, and false leads followed. On the third day, they traced his route. “My father had boarded a bus from Colaba Market and travelled to Antop Hill in Wadala.” He was eventually found at an ashram in Panvel and brought home.

The episode forced difficult choices. Bhaiwala was briefly placed in an old-age home but returned within two months because his wife missed him deeply. After her death, he was moved to A1 Snehanjali, a dementia care home in Nalasopara, where he lived until his death at 96.

Home away from home

A1 Snehanjali was founded in 2013 after its founder, Sailesh Mishra, 60, found a garden bungalow in Nalasopara West that he felt suited people with dementia. Bhaiwala was the centre’s second resident. “This is not an old-age home or a nursing facility,” Mishra says. “It is a home where I would feel comfortable keeping my own parents, and the staff does not even wear uniforms so that it does not feel institutional.” The centre has five twin-occupancy bedrooms and shared spaces, as isolation worsens dementia.

A fixed routine structures the day. Mornings begin around 6.30 am with walks, light exercise and breakfast, followed by outdoor time, spiritual prayer, music and group activities. Lunch is shared; evenings wind down with tea, games and short walks.

“Finding trained dementia care staff in India remains a challenge, so the focus here is on attitude rather than formal education,” Mishra says. The ratio is one caregiver for every three residents. “A doctor visits weekly,” he adds. “A physiotherapist visits once every 15 days, and a psychiatrist once a month. Doctors are available on call at all times.” Visiting hours are fixed to avoid agitation.

Back to school

The Dignity Dementia Day Care Centre in Mahim, run by the Dignity Foundation, has worked with senior citizens since 1995 and recently opened an other centre in Malad East. “These are strictly daycare centres, not residential facilities,” says CEO Javed Sheikh. The aim is to support families and slow the progression of dementia and Alzheimer’s. Detection remains a major challenge. “There is no single tool for early diagnosis and no clear dementia policy at the city or national level,” Sheikh says. Symptoms are often dismissed as normal ageing. “Dementia can escalate very fast,” he adds, recalling a man who left Mumbai well for Canada, suffered a vascular episode mid-journey, and failed to recognise his son on arrival. He was diagnosed there, where systems are better prepared.

“The centre functions much like a child daycare, with patients being at the centre from 10 am to 4 pm,” Sheikh explains. The centres offer transport, structured activities, meals and snacks. Mahim serves up to 25 patients, Malad 20. “Families usually come through hospital referrals, visit the centre, and opt for a short two-day trial before enrolment,” he says. Costs start at a subsidised Rs 17,000 per month.

A time for tough choices

Specialised dementia centres offer vital support for patients and families, despite the stigma attached to placing parents in such facilities. They offer what many homes cannot: consistent, trained care by people who understand the condition.

Counselling psychologist Carol D’souza, 64, from Bandra, made that decision for her mother when care at home became unmanageable. “I realised I could no longer manage her care at home,” she says. “My mother was a private and disciplined woman, she took her health seriously, walked daily, and solved crossword puzzles.” Subtle changes followed. “She failed to recognise a familiar shop on Hill Road and got confused while paying an auto driver.” Arguments with her mother and the maid, often over money, became frequent and out of character.

One incident proved decisive. “One morning at 5 am, my mother went missing from the house.” During the monsoon, she had walked out in a nightgown and slippers after the building gate was left open. She returned hours later, after police intervention. Medication proved difficult; her psychiatrist told D’souza that 80 per cent of dementia patients resist it. After visiting several homes that lacked adequate security, she chose a specialised dementia centre that could keep her mother safe.

Support for caregivers

Some centres also run support groups for caregivers. Psychiatrist Naazneen Ladak, managing director of BHN Eldercare Centres, says that when a person with dementia shows anger or aggression, reasoning rarely helps. The focus instead is on staying calm. Staff are trained to pause, let episodes pass, and gently redirect patients to familiar topics or activities they enjoy. Repetitive questioning, she notes, often offers comfort or fills memory gaps and must be met with empathy.

Before admission, the centre conducts a detailed assessment covering medical history, emotional triggers, likes, dislikes, allergies and family bonds. “We even take note of birthdays and fond memories, as these help the staff offer comfort at difficult moments.” Families usually turn to such centres when round-the-clock care becomes unmanageable, or when safety, medical supervision and social contact become concerns. Ladak does not believe in restraining patients to prevent wandering. “Rather we lock the facility and the main gate.” BHN Eldercare Centres operate across India and provide 24-hour care.

What families miss the most

Dr Bharat Vatwani, 67, a Borivali-based psychiatrist, often sees dementia patients when families are at breaking point. “Because of low awareness, patients usually come to us very late,” he says. “Often after they wander away, turn violent, or behave in ways the family cannot manage.”

Vatwani, who runs the Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation, says dementia progresses quietly. “Untreated blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol, smoking, or even asthma slowly reduce oxygen to the brain. Each episode feels minor, but over years, the damage adds up.”

Medication may slow the illness, he says, but reversal becomes unlikely. Even familiar homes can become confusing, especially after sunset. “They cannot find the bathroom, cannot control urine or bowel movements, and panic sets in,” Vatwani says. Families often respond with scolding, unaware of the cause. “Relatives must understand this is physical damage, not stubbornness.”

Small adjustments help: lights left on at night, clear bathroom markers, fixed furniture, and contact details worn on the body. “Expecting someone with dementia to travel alone or remember stations is dangerous,” Vatwani says. Hastak adds that behaviour is the hardest part. “Aggression, paranoia, and fear come from loss of brain control,” he says. “It is never deliberate.”

Both doctors stress that dementia affects entire families. Without early diagnosis, caregiver support, and a national policy, the burden deepens. “We forget that these people once shaped our lives,” Vatwani says. “They deserve dignity until the end.”

Back in her Colaba home, Khurshid Mehta tends to her mother, offering another careful sip of mango juice. The future will unfold quietly within these walls. For now, Mehta focuses on small comforts. “At this stage, I don’t want her to be corrected or pushed,” she says. “I just want her to feel safe and happy. That’s all that matters now.”

…

Assisted living spaces you can seek

https://nesteldercare.com/

https://www.jagrutirehab.org/

https://www.oliveeldercare.com/

https://banyantreegc.com/

https://cradleoflife.org.in

https://aajicare.in/

https://aasthaliving.in/

https://www.epocheldercare.com (Pune)