Astronomers studying an ultra-hot planet beyond our solar system have found something they did not expect: a thick atmosphere clinging to a world that should have lost it long ago.

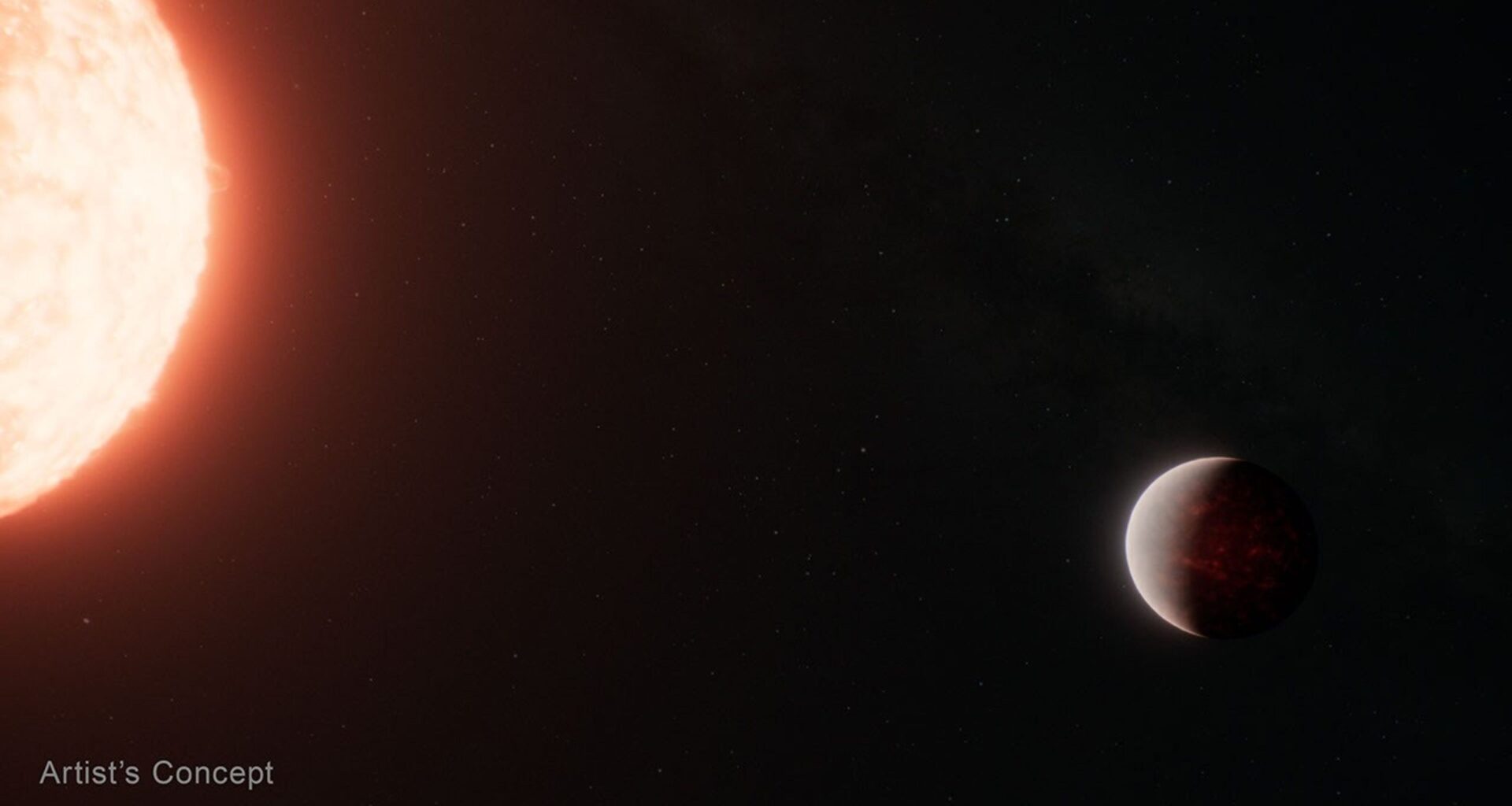

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, researchers observed TOI-561 b, a rocky super-Earth that races around its star in less than 11 hours. The planet sits so close to its star that one side is locked in permanent daylight, with surface temperatures high enough to melt rock into a global ocean of lava.

Despite those extreme conditions, Webb’s data suggests the planet is not a bare, airless rock. Instead, it appears to be wrapped in a substantial atmosphere hovering above its molten surface.

A Density That Didn’t Make Sense

TOI-561 b’s size and mass have puzzled astronomers for years. The planet is about 1.4 times larger than Earth, yet its density is lower than expected for a rocky world.

If the planet were made only of solid rock and metal, it should be heavier. A thick atmosphere offers a straightforward explanation, making the planet appear larger without adding much mass.

Webb Measures an Unexpectedly Cool Surface

To test whether an atmosphere was present, scientists measured the planet’s heat as it passed behind its star. A completely airless world this close to its star should reach nearly 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit.

Instead, Webb measured a much cooler dayside temperature of around 3,200 degrees. That gap is difficult to explain without gases above the surface absorbing infrared radiation and redistributing heat around the planet.

High-altitude clouds made of vaporised rock may also be reflecting some of the star’s energy back into space.

How an Atmosphere Survives Extreme Radiation

The discovery raises a bigger question: how does TOI-561 b keep an atmosphere at all? Researchers think the planet’s magma ocean may be continuously releasing gases that feed the atmosphere, while at the same time pulling some of those gases back into the interior. This constant exchange could help maintain the atmosphere even as some gas escapes into space.

The planet’s host star is unusually old and low in iron, hinting that TOI-561 b formed in a very different chemical environment from Earth. That origin may have left the planet unusually rich in volatile materials.

What Comes Next for TOI-561 b?

The findings are based on more than 37 hours of continuous Webb observations as the planet completed several orbits. Scientists are now analysing the full dataset to map temperatures across the entire planet and identify the gases in its atmosphere.

Rather than closing the case, TOI-561b has opened a new one, suggesting that rocky planets may be more resilient and more complex than scientists once believed.

![]() Published by Kerry Harrison

Published by Kerry Harrison

Kerry’s been writing professionally for over 14 years, after graduating with a First Class Honours Degree in Multimedia Journalism from Canterbury Christ Church University. She joined Orbital Today in 2022. She covers everything from UK launch updates to how the wider space ecosystem is evolving. She enjoys digging into the detail and explaining complex topics in a way that feels straightforward. Before writing about space, Kerry spent years working with cybersecurity companies. She’s written a lot about threat intelligence, data protection, and how cyber and space are increasingly overlapping, whether that’s satellite security or national defence. With a strong background in tech writing, she’s used to making tricky, technical subjects more approachable. That mix of innovation, complexity, and real-world impact is what keeps her interested in the space sector.