Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

Donald Trump’s attack on US economic institutions and rising concern over the quality of official data are propelling unofficial statistics into an evermore prominent role on Wall Street.

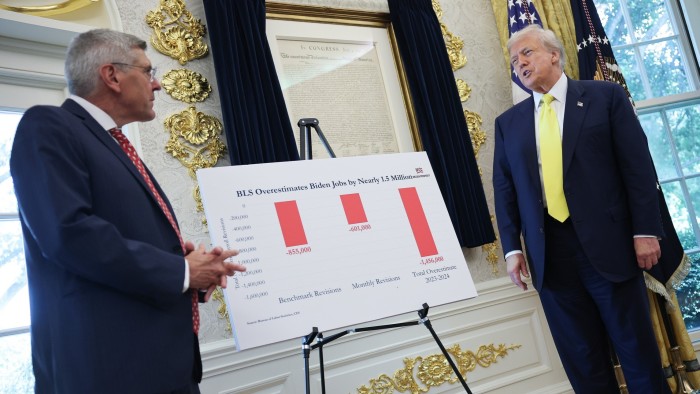

The US president has in recent weeks railed against the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which produces critical reports on inflation and the labour market. His attacks have come as the BLS has struggled with funding and staffing cuts that have made its data collection more challenging.

“We’ve always sort of taken for granted that we didn’t have to worry about the confidence of the government data because it set the standard for neutrality and reliability,” said Derek Tang, economist at LHMeyer. “That credibility is being impugned, whether fairly or not, right now.”

Last month, following a bleak jobs report, the president sacked BLS commissioner Erika McEntarfer and nominated loyalist EJ Antoni to replace her.

Trump’s administration escalated its assault against the BLS on Tuesday after it revised down its estimates of payroll employment in the year to March 2025 by more than 900,000 jobs. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said the revision underlined the need for “truthful and honest data” and added that “the BLS is broken”.

On Wednesday the labour department’s Office of Inspector General announced it was launching a probe into “challenges that [BLS] encounters collecting and reporting closely watched economic data”.

Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at consultancy RSM, said the controversy surrounding the BLS would “increase demand for private label data, which will over time create a widening gap between the haves and the have-nots”.

Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan © Hollie Adams/Bloomberg

Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan © Hollie Adams/Bloomberg

Brian Moynihan, chief executive of Bank of America, last month said government data that relied on surveys “just [isn’t] as effective anymore”. He noted that his vast bank can “watch what consumers really do. We watch what businesses really do.”

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon echoed Moynihan in a television interview this week.

“We get data like you wouldn’t believe,” Dimon said.

He added: “The government data is important. Our own data is important. We get data from non-government sources. And you can look at delinquency data, worldwide data, trade data. We get all of that.”

Long-standing private reports have recently risen in prominence, including a labour market report collated by payrolls processor ADP. Google searches for the ADP Employment Report have recently trebled.

New rivals have appeared on the market, such as Revelio Labs, which earlier this year launched its own monthly labour market statistics, marketed as a “more timely and granular” complement to BLS’s jobs data.

Wall Street research now also cites a variety of data sources, such as restaurant and hotel bookings and spending on credit and debit cards.

“I am encouraged by the explosion in data produced by the private sector over the past decade or so that can greatly enhance our understanding of the economy,” former Fed governor Adriana Kugler said last year.

The host of private data sets published by research firms, universities and industry groups can often outdo public sector alternatives on speed and detail. Thomas Simons, Jefferies’ chief US economist, said it helped to form a “mosaic view” of the market.

Free market advocates argue a shift to private figures would help improve trust in data, as it is harder for the government to exert influence over them.

“I think the private sector is more insulated,” said Adam Michel at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think-tank. “Trump explicitly criticised some of the Goldman Sachs economic forecasts and said their head economist should be fired. And that person still has their job — unlike the head of the BLS.”

But experts warn that while this may allow businesses to take quicker decisions, the reliability of such figures depends on them being backed up by “gold standard” official numbers.

“Private sector data might become increasingly important to look at if there are more gaps or if official statistics degrade or become less trustworthy,” said Jed Kolko at the Peterson Institute.

Recommended

“But we should not consider that a victory for private data. If that happens, if official statistics degrade, private sector data will get worse too.”

A wholesale move away from public statistics was unlikely in the near term, analysts said, not least because legislation requires the government to index certain targets to official data. And there are other measures that only government agencies are in a position to properly track.

“Reliable or not, there are some data that private industry simply can’t capture,” said Inflation Insights economist Omair Sharif. In these areas, which include some inflation metrics, he said “no serious economist is going to use a different measure”.