23 Dec 2025

At this year’s CTAD meeting earlier this month in San Diego, anti-amyloid antibodies—both the approved ones and “shuttled” versions hard on their heels—continued to command attention (see parts nine; 11; 12; and 13 from this meeting series). That said, speakers readily acknowledged that ridding the brain of amyloid will only go so far in slowing the progression of symptomatic AD. To do better, some see tau—specifically, its seedy extracellular form—as the next target.

More Antibodies take aim at seeded propagation.

New data ties tangle location to deficits in specific cognitive domains.

Three first-in-human studies for antibodies targeting different parts of tau suggest they are safe.

Stable isotope labeling shows target engagement in small trial of tau-ASO NIO752.

One presenter reported that as tau tangles pushed into successive brain regions, cognitive domains controlled by those very regions started showing deficits. These correlative findings stop short of demonstrating that tau’s successive entanglement drives these neuronal malfunctions; however, some scientists see the data as an indicator that traveling tau is the culprit. Antibodies are one way to try to thwart this purportedly neurotoxic march; alas, two contenders—bepranemab and posdinemab—recently missed their primary endpoints in Phase 2. Undeterred, scientists are moving new antibodies into the clinical stream. Case in point: results from first-in-human studies of three tau antibodies—all aiming to stop seeded tau propagation in its tracks—were presented at CTAD. All seemed safe, yet, as is the case with all conventional antibodies, only a tiny percentage crossed into the CSF.

Others are taking a blanket approach, aiming to take down tau expression with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). In a Phase 1 trial of a tau-ASO, NIO752, stable isotope labeling kinetics are being used to gauge which forms of tau take the brunt.

After a series of antibodies taking aim at N-terminal tau all failed, researchers have shifted their focus to tau’s midsection. It houses tau’s aggregation-instigating, proline-rich and microtubule-binding regions, aka MTBRs (Apr 2018 conference news). At last year’s CTAD, one antibody aiming at the MTBR, bepranemab, was the first to demonstrate an effect on tau tangles on tau-PET scans (Nov 2024 conference news). While bepranemab failed to benefit cognition across the whole Phase 2 cohort, it did appear to slow decline a bit among ApoE4 non-carriers who started the trial with low levels of tau. It was the familiar story of a missed primary but perhaps a ray of hope in a small subgroup.

At this year’s CTAD, Saori Shimizu from UCB presented tau-PET findings from an open-label extension of this trial, called TOGETHER. In its placebo-controlled portion, 466 participants had been randomized to monthly infusions of 45 or 90mg/kg bepranemab, or placebo, for 80 weeks. Of them, 387 enrolled in the 48-week extension, where the treatment groups continued on their original dose and the former placebo group was split evenly to receive 45 or 90mg/kg bepranemab.

Shimizu reported tau-PET findings across both parts of the trial. As expected, former placebo participants came into the OLE with higher tau burdens than those who had been receiving bepranemab. Their tangle load leveled off over the course of the extension. For those who had previously received bepranemab, their tangle burden also remained flat relative to baseline throughout the OLE. Large, overlapping error bars at every time point demonstrated the substantial variability in tau-PET measurements between groups. To the chagrin of some attendees, Shimizu said that p values were not calculated for the OLE, so it was unclear if any effects were significant.

One week prior to the CTAD meeting, Johnson & Johnson announced that it was halting its Phase 2 trial evaluating posdinemab in people with early AD. An interim analysis had suggested no sign of a cognitive benefit (press release). The antibody binds tau’s proline-rich region, and reportedly intercepts seeded tau propagation in cell-based and animal studies.

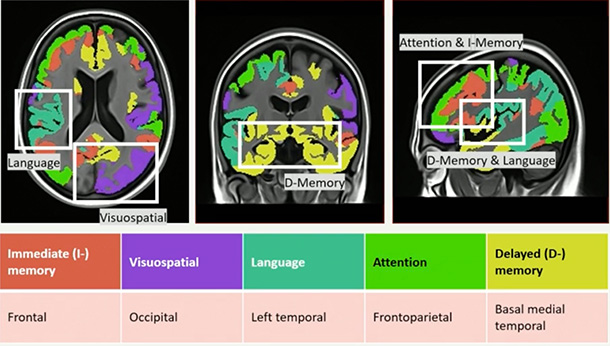

While no outcome data from the trial, called Auτonomy, were presented at CTAD just yet, J&J’s Xingjian Zhang used extensive tau-PET data collected in the trial to investigate how spatial progression of tau pathology might relate to cognitive deficits in specific domains. In San Diego, Zhang presented findings from this analysis. It correlated the spatial distribution of tau tangle pathology with scores on five cognitive domains assessed in the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Creating a voxelwise map of tau-cognition associations, Zhang found that the Tau-RBANS associations lined up with known cognitive functions mediated by different brain regions. That is, tangles in the medial temporal lobe associated with deficits in delayed memory; while pathology in the left temporal, occipital, frontal, and frontoparietal regions were correlated with lower scores on tests of language, visuospatial, immediate memory, and attention, respectively.

Map of Tangle Trouble. Tau deposits in a given region associate with deficits in specific cognitive domains. [Courtesy of J&J]

Zhang next wanted to extend this analysis to the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative’s rich tau-PET dataset. Alas, ADNI does not use the RBANS. Instead, it uses the ADAS-Cog13, which doesn’t break down scores into cognitive domains. To translate ADAS-Cog13 into RBANS-like domains, J&J tapped neuropsychologists to assign each question on the ADAS-Cog13 to the appropriate domain, creating a “ADAS-CogRB.” Applying this translated scale to the Auonomy cohort, who had taken both RBANS and ADAS-Cog13, suggested it was consistent with RBANS in terms of its tangle-cognitive domain map. In ADNI, then, the scientists identified similar regional associations between tau entanglement and struggles in specific domains, suggesting that as tangles inundate a given region, the cognitive functions subserved by that region start to falter.

Zhang interpreted this data as supportive of extracellular tau seeds as a viable therapeutic target. That said, such correlations leave open the possibility that tau tangles merely mark, rather than drive, neuronal malfunction in a given region. Zhang did not discuss J&J’s recent decision to axe posdinemab.

Lined Up at Phase 1

Despite the string of negative trials, many scientists believe the rationale for targeting extracellular tau seeds remains strong. In support of this, CTAD featured Phase 1 data for three such antibodies.

First up to bat, BMS-986446. Developed by Prothena as PRX005 before Bristol Myers Squibb picked up the program, this antibody latches on to the R1, R2, and R3 repeats of tau’s MTBR. It had been deemed safe and well-tolerated among healthy volunteers in a previously reported single ascending dose study. In San Diego, David Walling, of the Salt Lake City-based contract research organization CenExel, presented results from a small multiple ascending dose study. Walling is a site investigator at a CenExel site in Los Alamitos, California. The trial enrolled 10 healthy volunteers and 12 people with biologically confirmed, early AD.

Participants were randomized 3:1 to three monthly infusions of BMS-986446 or placebo. In all recipients of BMS-986446, the antibody was safe and well-tolerated. A total of 17 adverse events occurred in 13 participants throughout the trial, including three who received placebo and 10 who took BMS-986446. Thirteen of these events were mild; four moderate. They included headache, sleepiness, and joint pain. There were no serious or severe adverse events or deaths, and none that prompted discontinuation. No participant mounted detectable antibody responses against BMS-986446. On par with other monoclonal antibodies, the concentration of antibody in CSF was 0.2 percent of that in the plasma.

A Phase 2 trial is now underway in early AD.

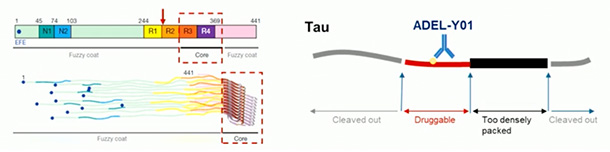

Next up was ADEL-Y01, an IgG1 pitched at acetylated tau. Specifically, it targets tau acetylated at lysine-280 within the infamous hexapeptide motif—VQIINK—located in its second MTBR. This form of tau is thought to promote seeded aggregation. Co-developed by ADEL, Inc. and Osotec, Inc. in South Korea, the antibody is also being evaluated in dosing studies at CenExel.

Take Down That Ace. ADEL-Y01 binds acetylated K280 within R2 (red arrow, left). This spot is located in a “druggable” region of tau (red on right), as it is neither cleaved out nor buried within the fibril core. [Courtesy of ADEL, Inc.]

In San Deigo, ADEL’s Min-Seok Kim showed data from a recently completed single ascending dose study, which evaluated safety and pharmacokinetics of 2.5, 7.5, 20, 50, or 100mg/kg ADEL-Y01 or placebo, among 40 healthy volunteers. All doses were safe and well-tolerated, with most adverse events mild or moderate in severity, and none tied to the drug. No anti-drug antibodies were detected. The half-life was two to three weeks, with a CSF-to-serum ratio of 0.017 percent one day after injection, and 0.14 percent two weeks later.

A multiple ascending dose study is ongoing in people with biomarker-confirmed MCI due to AD or mild dementia. Participants will be treated for 12 weeks, with three monthly infusions of 30mg/kg or 60mg/kg ADEL-Y01, or placebo. Safety and tolerability is the primary endpoint, while secondaries include pharmacokinetics, CSF exposure, MMSE, and CDR-SB. Multiple fluid AD biomarkers will be assessed as exploratory outcomes.

Also at CTAD: results from first-in-human studies for a third antibody, VY7523. Developed by Voyager Therapeutics, in Lexington, Massachusetts, VY7523 is an IgG4 headed for the C-terminus of pathological tau. It was generated via immunization of mice with paired helical filaments extracted from the human brain. Voyager’s Elena Ratti showed data from a single ascending dose study, which tested six doses of VY7523 or placebo among 48 healthy volunteers. No concerning safety issues emerged. All of the 17 adverse events that occurred during the trial were mild to moderate in severity, and there were no infusion related reactions. Five events—headache, nausea, dizziness, and two events of chest pain—were deemed related to VY7523 by the site investigator. Anti-drug antibodies were detected in one person. The half-life of VY7523 was 22-29 days, and the CSF to serum ratio was 0.3 percent. Ratti said that a multi-dose study in people with early AD has begun.

One attendee asked what was the rationale behind a claim, made by Ratti and other presenters, that exposure in the CSF equates to exposure in the brain, noting that antibodies are known to travel from the blood into the CSF not via the brain, but via the choroid plexus. The question resonated with other work presented at the meeting, in which TfR-shuttled antibodies were shown to distribute throughout the brain parenchyma while their conventional counterparts lingered in vessel-adjacent interstitial fluid, and CSF (Dec 2025 conference news).

Ratti responded that preclinical animal studies suggested VY7523 did penetrate the brain, adding, “What will be critical for demonstrating whether the CNS is properly exposed is the translation into a potential efficacy that we are hoping to see with the next study in terms of tau-PET signal.”

If indeed VY7523 does cross into the CNS and nudge tau-PET, scientists won’t know until after both multi-dose and Phase 2 studies have been completed.

Tracking Tau Takedown with SILK

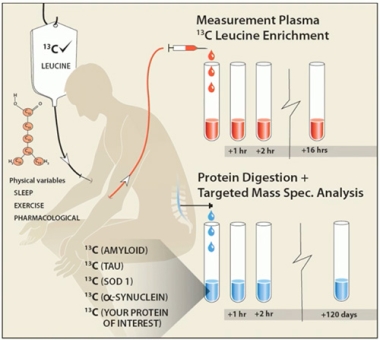

In San Diego, Ross Paterson of University College London presented a way to find out sooner if an anti-tau therapeutic engages its target in the brain, and to what end. Paterson presented interim data of a Phase 1b trial evaluating NIO752, a tau ASO. This multi-center trial is a collaboration between UCL, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network Trial Unit (DIAN-TU) at Washington University in St. Louis, and Novartis, which developed NIO752 to reduce tau expression.

Paterson said that using fluid biomarkers to gauge how NIO752, or other tau-targeted therapeutics, are affecting tau expression in the brain is challenging for several reasons. “There is a large repository of intraneuronal tau, and yet we try to measure that in the CSF and plasma, where concentrations are much lower, different species exist, and the half-life is very slow,” Paterson said. “This creates a mismatch between what’s happening inside the neuron, and what you are able to measure.”

To surmount this problem, Paterson and colleagues used stable isotope labeling kinetics. The SILK technique involves infusion of 13C-leucine, a stable isotope that weighs six daltons more than the version that exists in nature. As 13C-leucine incorporates into newly translated tau proteins, scientists can determine the age of fragments of tau detected in the blood or CSF at different times after isotope infusion by way of mass spectrometry. What’s more, they aimed to discern how NIO752 affects expression of tau without interference from lingering pools of the protein.

How Much Tau is Made? In stable isotope labeling kinetics, intravenously infused 13C-leucine incorporates into newly translated proteins, including tau. Repeat sampling and mass spectrometry enables scientists to estimate the rate of tau translation. [Courtesy of Ross Paterson, UCL]

The Phase 1b trial, dubbed NIO-SILK, is enrolling five people with sporadic AD and five people with autosomal-dominant AD. They are randomized 3:2 to receive an intrathecal injection of NIO752 or placebo, followed 48 hours later by a 16-hour intravenous infusion of 13C-leucine. CSF will be collected three times over the subsequent 85 days. At day 124, participants will be given an open-label dose of NIO752, and monitored—sans SILK—until day 208. In San Diego, Paterson showed results from the first five participants to have enrolled, as well as from 10 external controls with AD who underwent tau-SILK measurements at WashU.

CSF samples from external controls with AD revealed a gradual rise in the ratio of labeled to unlabeled tau in the CSF over the first several days following isotope infusion. The slope of that rise could be used to infer the rate of tau translation. Paterson showed blinded interim data from the ongoing NIO-SILK trial, where three participants received NIO752 and two placebo. Although the groups remained blinded, there was a tantalizing trend in which tau translation appeared to have slowed in three participants relative to the other two.

In future analyses, Paterson said that tau-SILK measurements will be used to gauge how NIO7523 affects the production of different tau isoforms, including hyperphosphorylated forms and different fragments such as eMTBR-243.

This trial asks a lot of its participants. Paterson said that participants are motivated, stick with the trial, and tolerated the various infusions and lumbar punctures performed throughout the trial well, with no serious adverse events or early drop-outs so far. He hypothesizes that tau-SILK will prove superior to static measures of tau in detecting early changes in tau expression mediated by NIO752 and other tau therapies.

Could tau-SILK be rolled out in larger, late phase trials? Unlikely, Paterson said. The multiple infusions and lumbar punctures make the procedure too invasive and labor intensive to be deployed in large cohorts or in clinical practice. However, he thinks it could be helpful to assess target engagement in early, dose-finding trials in tens, rather than hundreds, of participants. —Jessica Shugart

News Citations

Amyloid Immunotherapy Affects Multiple Alzheimer’s Pathologies 18 Dec 2025

From CTAD: For Brain Shuttles, It’s All About Distribution 19 Dec 2025

Four Years After Conception, ALZ-NET Registry Is Growing 19 Dec 2025

Leqembi in Asia: ARIA Is Low, Infusion Reactions Are Common 19 Dec 2025

To Block Tau’s Proteopathic Spread, Antibody Must Attack its Mid-Region 5 Apr 2018

Finally, Therapeutic Antibodies Start to Reduce Tangles 14 Nov 2024

Therapeutics Citations

External Citations

No Available Further Reading