Saturn’s moon Titan may not be hiding the vast underground ocean scientists once envisioned.

A fresh look at Cassini’s radio-tracking data reveals that the moon is losing roughly 3 to 4 terawatts of heat, a signal that points toward a slushy interior instead of a continuous sea.

This is an important distinction for life, which relies on water’s ability to circulate nutrients from rock.

Flavio Petricca led the reanalysis at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). His work links spacecraft tracking with lab-tested ice physics at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle.

Cassini gravity data

Cassini spent years orbiting Saturn, and its Titan flybys produced radio tracking data that let scientists test gravity models.

Engineers at JPL tracked the craft using Doppler shift, frequency change caused by relative motion, to sense tiny speed changes during flybys.

Those speed changes reflect gravity, but small errors can hide a time lag unless analysts squeeze the noise down.

Early ocean confusion

In 2008, researchers tied Titan’s changing shape to tides from Saturn, and they leaned toward a buried ocean.

During repeated squeezing and stretching driven by gravity, known as tidal flexing, a stiff shell moves less than a softer interior layer.

The early measurements fit more than one interior, so the reanalysis had to look for more clues.

The mystery of Titan’s interior

The experts compared Titan’s strongest pull with its biggest bulge, and the two peaks did not line up.

Tidal dissipation, energy lost as heat during repeated flexing, turns motion into warming when layers rub and deform.

“That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses,” said Petricca.

Planetary scientists use a Love number, a measure of how a body deforms under tides, to summarize Titan’s response.

The real part captures how much the surface rises, while the imaginary part captures the delay linked to heat loss.

Earlier work mostly pinned down the real part, but the reanalysis pulled out the missing imaginary piece. The new fit stacks thick ice above a rocky core, and it places melt in scattered pockets.

Small pockets of water

Deep high-pressure ice can sit near melting and behave like slush. Because pockets stay separated, chemicals and heat move differently than they would through a connected ocean layer.

Inside Titan, repeated tides turn orbital energy into heat, and the research suggests that most of that loss happens deep.

Slow, churning motion within the ice, known as convection, can carry heat upward long before large-scale melting sets in. That balance keeps Titan mostly frozen while still allowing small water pockets to appear where pressure and heat meet.

In experiments at UW, researchers recreated Titan-like pressures to map when ice softens or melts inside deep layers.

Those measurements track thermodynamics, rules that govern heat and phase changes, when water turns into denser ice forms.

Improved laboratory measurements from UW narrow uncertainties in the gravity models, but the results still hinge on how evenly Titan’s ice layers are actually mixed.

Titan surface lacks water pockets

The reanalysis suggests some freshwater pockets could reach 68 degrees Fahrenheit, and smaller volumes can concentrate nutrients and chemical fuel.

Warm pockets could suit simple microbes, but isolated spaces also limit energy flow and long-term stability for bigger organisms.

On Titan’s surface, temperatures hover near -290 degrees Fahrenheit, and methane and ethane form lakes and rain there.

These hydrocarbons, molecules made of hydrogen and carbon, stay liquid because cold makes water ice behave like hard rock.

Surface liquids can feed chemistry, but any water-based life would need shelter in the warmer pockets described deeper down.

Dragonfly’s planned reality check

NASA has confirmed a Dragonfly launch date of July 2028 for a rotorcraft mission to Titan.

Dragonfly will hop between sites and listen for quakes, because shaking waves travel faster through solid ice than liquid.

If the readings match a slushy interior, the mission can target areas where surface organics meet internal water pathways.

Future research on Titan

Uncertainty remains about how connected the melt pockets are, and whether salts or ice cages that trap gas molecules thicken the layers.

Laboratory tests struggle to mimic weeks-long stressing, so the strongest predictions still depend on how real ice grains slide and heal.

Future work must connect those micro-scale properties to spacecraft data, or the next debate will replay in another moon.

Taken together, the reanalysis links Titan’s delayed squeeze to deep slush, and it reframes how we read old flyby signals.

Dragonfly and future tracking studies may test these pockets directly, yet key uncertainties will persist until lab experiments replicate Titan-like pressures.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

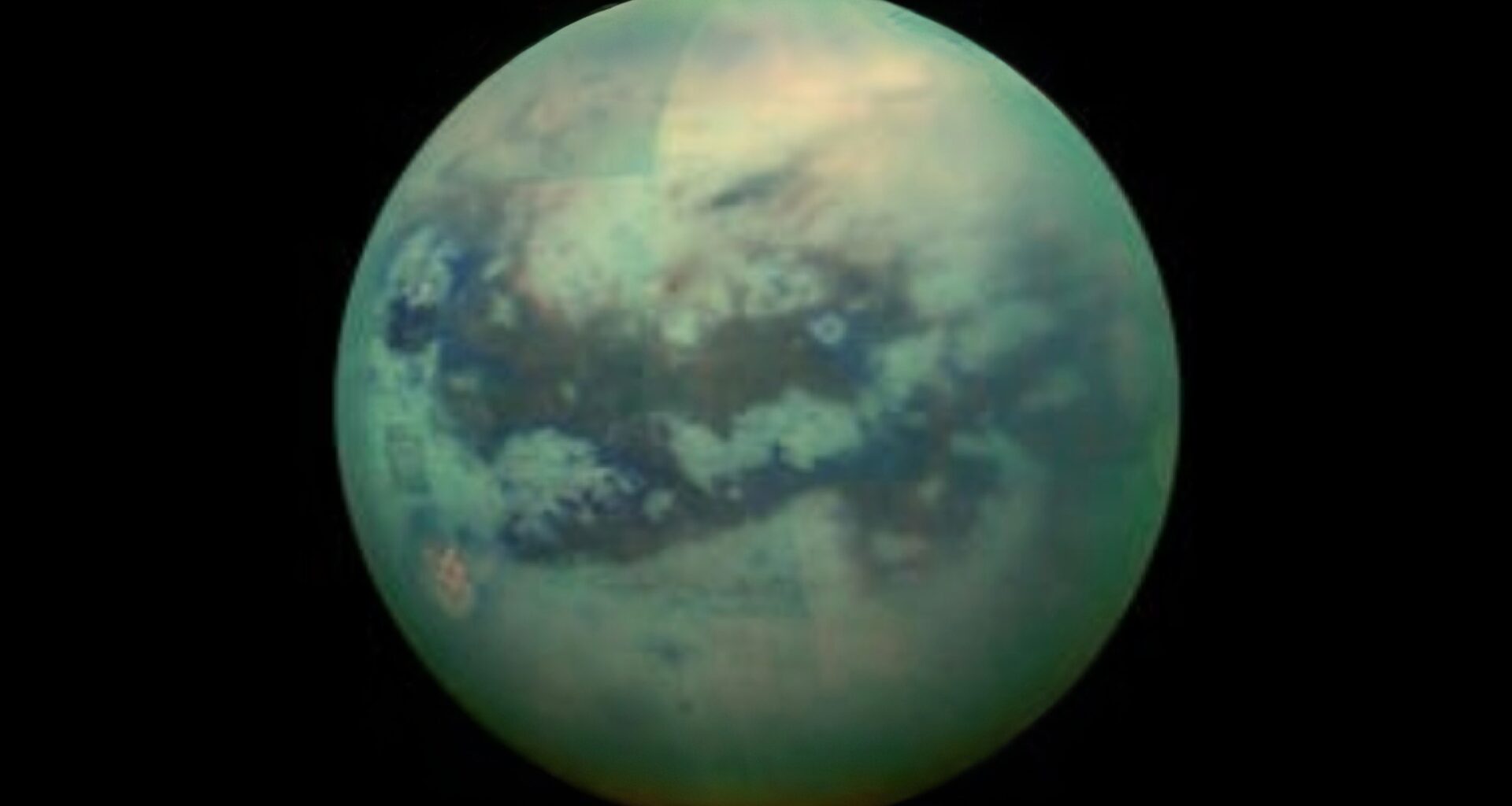

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–