A new super simulation called FLAMINGO maps the universe from its first moments to today, and it intensifies a stubborn cosmology puzzle.

Even after tracking ordinary matter alongside dark matter, the model still predicts more clumping than astronomers actually measure.

The team worked across the Virgo Consortium in Europe and the United Kingdom, using software built for huge cosmological calculations.

Their headline result sounds simple but remains unsettling, because the real universe looks smoother than the standard recipe predicts.

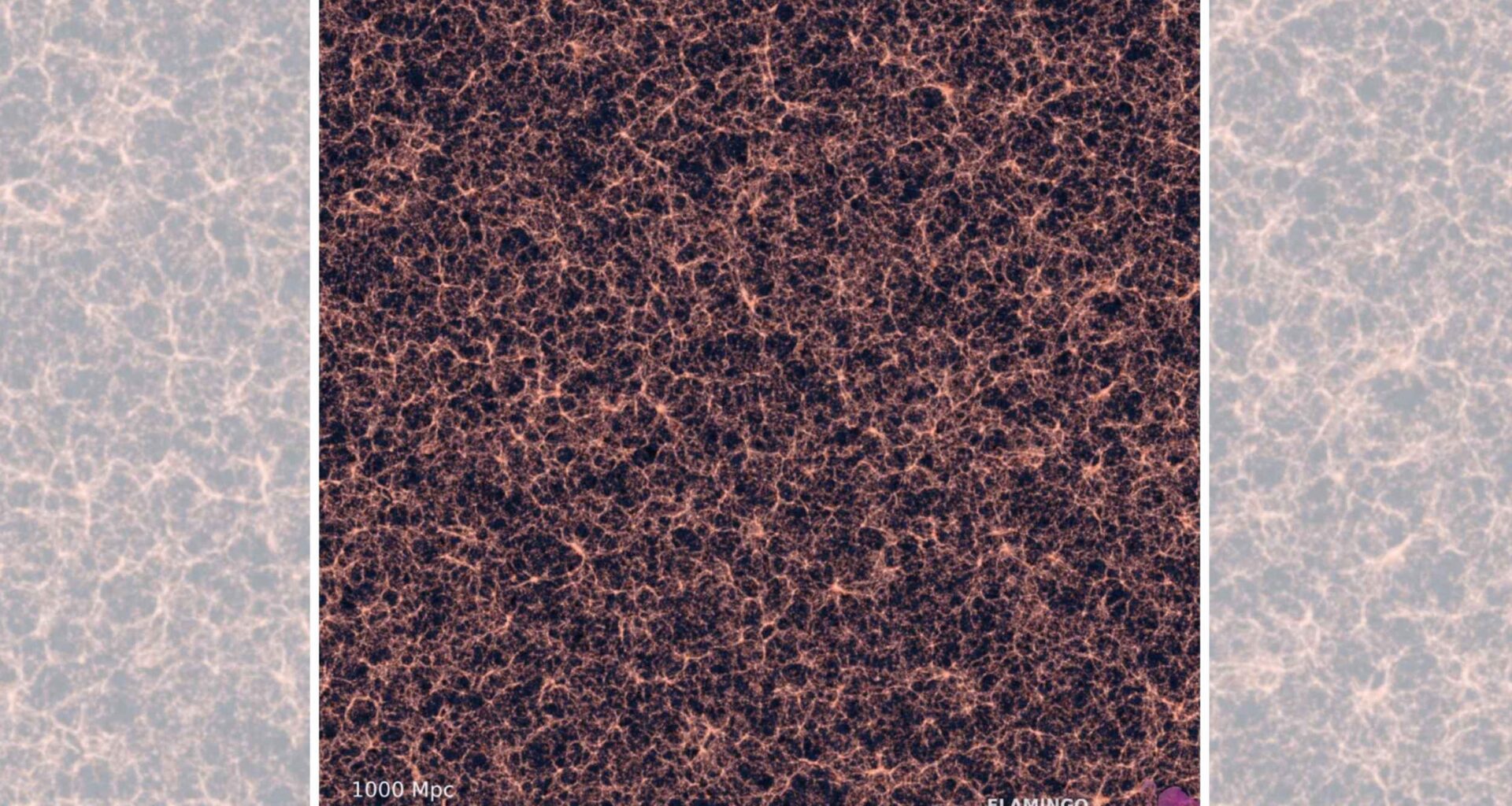

The FLAMINGO simulation

The team built FLAMINGO, a suite that follows roughly 300 billion particles from early times to the present.

Those runs reproduce observed galaxy and cluster properties while preserving a clear view of how structure grows across cosmic time.

Rather than treat gas as an afterthought, the code models how fluids move under forces, modeling a true hydrodynamical evolution of ordinary matter.

That means pressure, starlight heating, and black hole activity can push or pull matter, changing where it collects and how halos form.

The associated work was led by Ian G. McCarthy, professor of theoretical astrophysics at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU).

His research focuses on the growth of cosmic structure and the hot gas in galaxy clusters. FLAMINGO simulation also includes neutrinos, tiny lightweight particles that stream through space in vast numbers, because they slow growth slightly by carrying free-streaming energy.

Adding those effects lets the code trace an interconnected cosmic web fed by gravity, gas pressure, and radiation from forming stars.

One number nags cosmology

To compare theory and data cleanly, cosmologists use the S8 parameter, a single statistic for the strength of matter clustering on common scales.

A higher value means lumpier structure, while a lower value means a smoother spread of matter across the sky.

Recent lensing results from the Dark Energy Survey point to a lower value than models anchored by early light.

In those maps the weak gravitational lensing, a tiny shape distortion caused by intervening mass, reveals how matter really clumps nearby.

Early-universe predictions come from the analysis of the cosmic microwave background, faint leftover light from the Big Bang, which yields a higher expected value.

That viewpoint fits much of modern astrophysics, so the disagreement with galaxy lensing maps sticks out.

The mismatch has earned a name, the S8 tension, and it has persisted across independent analyses using different telescopes.

Scientists want to know whether the issue comes from theory, from subtle measurement biases, or from something genuinely new.

What was tried, what was found

To probe that gap, the team varied baryonic matter, matter made of protons and neutrons, feedback and tested extremes in a dedicated study.

Supernova winds and voracious black holes were allowed to shove gas around, making structures lighter or heavier than in simpler runs.

They also explored neutrino mass, the tiny weight carried by those ghostlike particles, because heavier neutrinos slow the growth of structure more strongly.

Across all of these branches the simulated clumping remained higher than seen in today’s lensing surveys, leaving the central mismatch intact.

“Here I am at a loss. An exciting possibility is that the tension is pointing to shortcomings in the standard model of cosmology, or even the standard model of physics.” said Joop Schaye, a professor at Leiden University and co-author of the work.

More testing is needed

Taken together, the evidence suggests the universe formed its structure as expected for much of its history, then built slightly less than the theory forecasts.

Mid-era probes line up neatly with the model, while present-day maps look smoother than that baseline.

“We do not know, which is what makes this so exciting,” said McCarthy. He argues the simulations now remove many easy explanations and point squarely at physics to be tested next.

Investigator teams are weighing modified gravity, theories that tweak how gravity works on huge scales, alongside dark matter that can nudge itself through rare interactions.

Both ideas must still respect precise tests in the solar system, so researchers tread carefully while designing sharper checks.

Lessons from FLAMINGO simulation

Upcoming surveys and improved analysis pipelines will tighten lensing maps, and parallel theory work will push predictions and uncertainties into cleaner contact.

Either the standard picture will absorb the tension with better modeling, or the evidence will force a deeper rewrite.

The study is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–