Title: The First Star-by-star N-body/Hydrodynamics Simulation of Our Galaxy Coupling with a Surrogate Model

Authors: Keiya Hirashima, Michiko S. Fujii, Takayuki R. Saitoh, Naoto Harada, Kentaro Nomura, Kohji Yoshikawa, Yutaka Hirai, Tetsuro Asano, Kana Moriwaki, Masaki Iwasawa, Takashi Okamoto, Junichiro Makino

First Author’s Institution: RIKEN center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences, Wako, Japan.

Status: Published in SC ’25: Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis [open access]

When we simulate things in astronomy, we usually want the simulations to be as accurate as possible. However, we often run into the problem that astrophysical phenomena are incredibly complex, making them difficult to simulate with our current hardware. This is particularly true when attempting to simulate an entire galaxy composed of hundreds of billions of stars, vast clouds of interstellar gas, and a massive halo of invisible dark matter.

To model these systems, astronomers typically use a mix of methods. Stars and dark matter are modeled as N-body particles contributing as gravitational sources in the simulation. Meanwhile, interstellar gas is modeled with smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) where the gas distribution is “smoothed” over a specific area to represent a continuous fluid. Instead of a particle being a single point in space, it is treated as a blurry cloud. The properties of one particle (like its density and pressure) are spread out over a “smoothing size” called the kernel size. By overlapping a number of these particle kernels, the simulation creates a smooth, continuous map of the gas density rather than a series of isolated points.

However, unlike N-body particles that only interact through gravity, gas particles constantly push against each other through pressure and change temperature through heating and cooling. The simulation must constantly recalculate the kernel size and density for every single particle to ensure the “fluid” stays continuous. This becomes especially important if something violently disturbs the gas…

Here is the problem

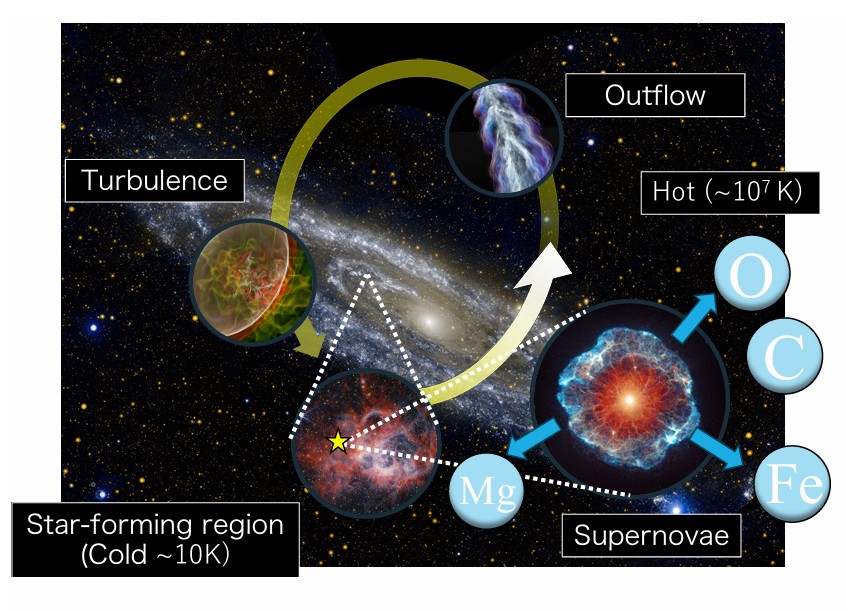

The real bottleneck in these simulations is a matter of time and scale. Galaxies are massive, but the most critical events within them are localised and violent. When a massive star dies, it explodes as a supernova (SN). Supernovae inject energy and materials created inside stars into their surrounding gas, driving turbulence and outflows. The timescale of an expanding SN shell is years, but the timescale of the galactic disk rotation is hundreds of millions of years. This huge range of timescales makes performing high-resolution galaxy simulations very challenging. To capture SN explosions and accurately model how the injected energy and gas interacts with the simulation in the local region around the SN, the simulation must drop its “timestep” (i.e. the amount of time that passes between each calculation) to a very small interval. But the simulation can only move as fast as its smallest timestep, so these tiny, localised explosions effectively bring the entire galactic simulation to a crawl if you try to simulate too much at a time. A representation of the process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The figure shows a range of astrophysical processes that must be taken into account when you want to simulate a galaxy that contains both evolving stars and gas. As the stars evolve, some will go supernova and the expanding ejecta will influence the dynamics of the surrounding gas in the region, creating turbulence and outflow. Figure 1 in the paper.

So far, the maximum number of particles used in state-of-the-art simulations has been limited to less than one billion. With the Milky Way containing some 100 to 400 billion stars, this number falls a little short if you want something closer to reality. If you want to simulate a galaxy with a lot of stars with current methods, one particle has to represent a whole group of stars, which limits your ability to understand what’s actually going on with the individual stars. This has limited simulations to either low-resolution models of large galaxies or high-resolution models of very small ones.

But here is a cool novel trick

To break through this barrier, the authors of today’s paper developed a novel integration scheme that uses Machine Learning (ML) to bypass the most computationally expensive parts of a galaxy-scale simulation.

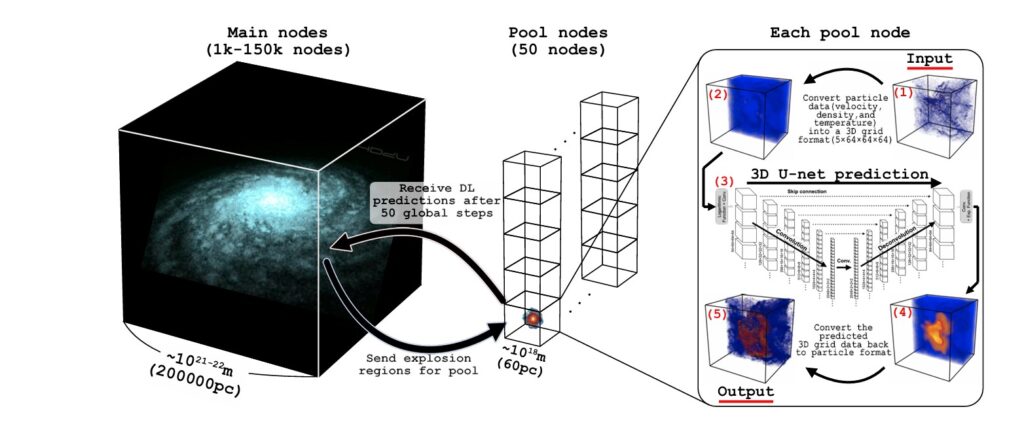

Instead of painstakingly calculating the expansion of each supernova, the new system uses Deep Learning (DL) to predict the final result. The workload is split between two types of computational nodes:

Main nodes: These handle the standard, large-scale N-body/SPH integration for the entire galaxy.

Pool nodes: A smaller group of nodes dedicated to running the DL model.

When the simulation detects a star is about to go supernova, it “picks up” the gas particles in a 60-parsec (roughly 195 light-year) cube around the star and sends them to a pool node. The main nodes then continue to calculate the gravity and movement of the rest of the galaxy. Crucially, they do this without adding the explosive energy yet. They simply keep the stars and gas moving on their normal paths. While the main nodes continue their work, the pool node uses a pre-trained neural network to predict exactly how that gas will be distributed 100,000 years later. The pool node then sends this “future” data back to the main simulation, where the particles are swapped in seamlessly. Because these processes overlap, the simulation no longer has to slow down for individual explosions. A schematic of the process can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The figure shows a schematic illustration of the simulation method used by the authors. The main nodes of the simulation handle the big picture, calculating the gravity and movement of hundreds of billions of particles across the entire 200,000 parsec expanse of the galaxy. When the simulation identifies a star that is scheduled to explode in the next few moments of simulated time, it carves out a small cube of space (60 parsecs wide) around the doomed star. All the gas particles in that box are packaged up and sent to an available pool node. While the pool node uses a neural network to predict how that box will look 100,000 years after the blast, the main nodes continue integrating the rest of the galaxy without knowing the result of the explosion yet. The results are then sent back into the main simulation. Because the movement of the explosion shell is localised to a small section of the galaxy, the rest of the simulation doesn’t need the data right away. Simultaneously, because the process of calculating the result of the explosion is parallelised to the pool nodes, the main simulation doesn’t have to slow down. Figure 3 in the paper.

Because the explosion mostly affects its immediate neighborhood (the 60-parsec box), the rest of the galaxy doesn’t actually “need” to know the results of that explosion right away to keep its own orbital calculations accurate. By the time the global simulation on the main nodes reaches that 100,000-year mark, the new gas data is ready and waiting to be plugged back in. This allows the supercomputer to maintain a high speed across millions of CPU cores without ever hitting the brakes for a single star.

Simulating the Milky Way

The authors used this method to simulate the Milky Way. The model included a halo of mainly dark matter particles and with most of the stars and the gas in a rotating disk. With only 720 million stars, this is still a little short of a full Milky Way analogue. But when you count the gas and the dark matter particles, their simulation included over 300 billion particles, which is well past the billion particle barrier and what previous models have achieved.

They tested their model on a number of supercomputers where one had the equivalent of over 7 million CPU cores. Compared to current state-of-the-art models, they estimated this new method to be over 100 times faster for the same number of particles.

This means that for the first time, we can simulate a larger, almost Milky Way-sized galaxy, where every individual star is accounted for, rather than grouping them into “blobs” that represent hundreds of stars. At the same time we can also take into account the evolution of these stars and how this couples to the gas dynamics of said model galaxy. This allows us to track how elements like oxygen and iron spread from a single supernova to the next generation of stars and thus predict the chemical evolution of the galaxy.

Additionally, the supernovae bottleneck here is a specific version of a general problem with small timesteps in high-resolution simulations. The technique of replacing a small part of the simulations with deep learning models could be beneficial in various fields where it is essential to simultaneously simulate phenomena spanning both small and large scales or short and long timescales. This could be applied to simulations of cosmic large-scale structure formation, black hole accretion, as well as simulations of weather, climate, and turbulence.

For now, using deep learning to handle the “explosive details” (pun intended) of the simulation has enabled us to break the billion particle barrier and simulate a model that is closer to the true size of the Milky Way in a way that was previously out of reach.

Astrobite edited by Alexandra Masegian

Featured image credit: KPNO/NOIRLab, edited in MS Paint by Kasper Zoellner

![]()

I have a Master of Science in astronomy and I am currently working towards a PhD in physics and educational science. My greatest passion is the search for exoplanets and how stellar variability may influence the possibility of life. I am also interested in science outreach, education and discussing what Sci-Fi novel to read next!