When Mark William Lewis thinks about his songs, they summon a particular image in his mind. It’s a somber aesthetic — moody and grayscale, a world slightly warped and drained of color.

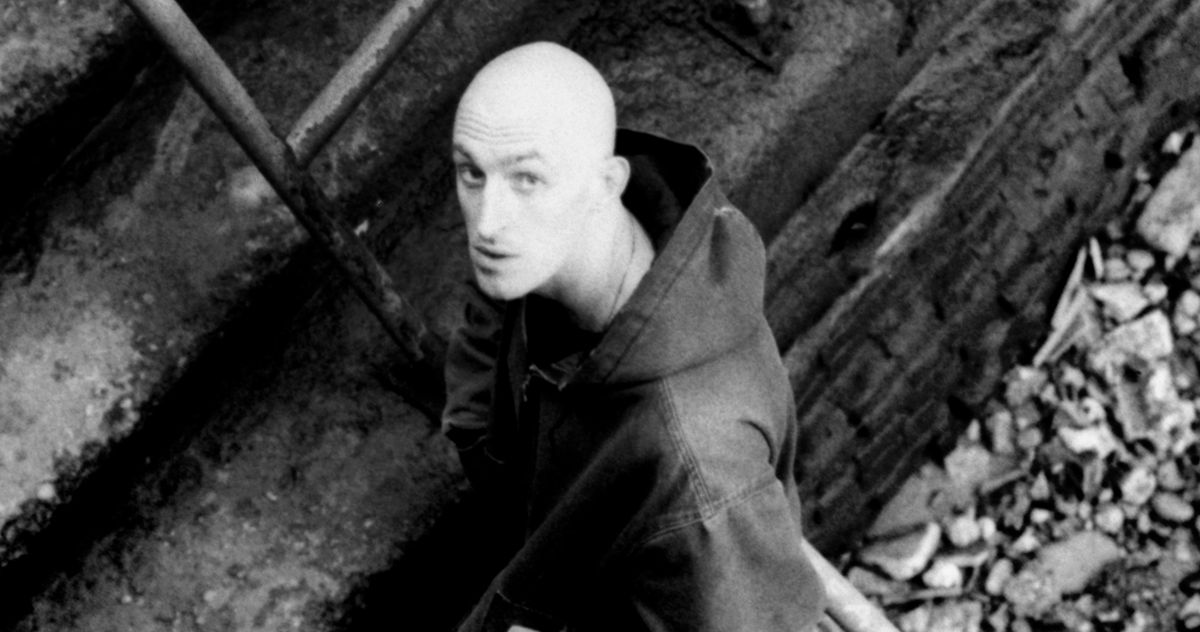

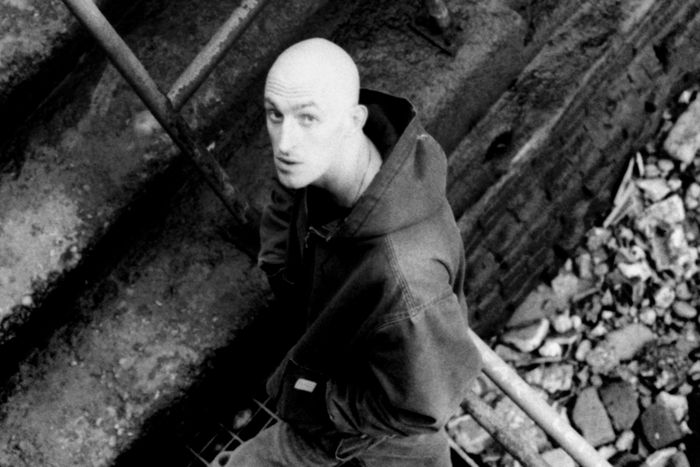

Consider, for example, the photograph that graces the cover of his forthcoming album, Mark William Lewis. As soon as he saw the image — shot last spring by veteran rock photographer Steve Gullick — “I knew that felt like the world I was trying to describe in my mind’s eye,” Lewis says. “It’s a bit murky. There’s an uncanniness to it.”

An undeniably cinematic image, it could be a promotional still from some new arthouse horror hit. Which is fitting, because Lewis recently became the first artist the film studio A24 has signed to its nascent record label, A24 Music, outside of a soundtrack context.

Though he may seem like he came out of nowhere, Lewis, a product of South London’s thriving DIY scene, has been working toward this for a long time. An early-30s singer-songwriter with a gruff voice and a knack for writing gloomily impressionistic tunes swathed in reverb and urban malaise, he grew up on a steady diet of poetry and magical-realist literature and sounds a bit like the genre-bending London artist King Krule’s harmonica-wielding cousin.

With a shaved head and an oversize black T-shirt, Lewis is soft-spoken and thoughtful, far from the imposing figure who lurks in his dark, haunted press photos. He and I spoke in New York at A24’s library, a high-shelved room that houses hundreds of volumes on cinema.

This is not your first album. I find it interesting when artists put out a self-titled album that’s not their debut. It signals that this is a redefining moment, a reinvention of what their music means. What made you decide to title the record after yourself?

The simple answer is that nothing else felt right. This felt right, firstly. And then I started thinking about what it signifies, which is, like you said, a kind of announcement: This is me; this is my sound. I went to a Philip Guston retrospective, and you see at the beginning where he’s younger and he’s kind of copying some people. Then he goes through a phase where he’s trying to find his thing, but it’s not really realized yet. And then you get to the fourth or fifth room and you start seeing the paintings that you know him for. I feel like this album is that room.

Your single “Tomorrow Is Perfect” is one of your more ambitious compositions, both lyrically and musically. Can you talk about what that song signifies for you?

I wanted to build a really rich tapestry of words — almost like an epic poem. I was trying to conjure a place in my imagination. The words are building this architecture of a place that’s kind of in my imagination but is also grounded in specifically my area, where I live, in Deptford. And I think, in the end, it’s a song where I’m really exploring my emotional and psychological state in the context of the environment where I was living. I suppose I wanted to do a magical-realist portrait of my life.

When you write lyrics, do you feel like they come from a more subconscious place for you?

Yeah. I think one reason I’m struggling to talk about it is because I think the most inspiring emotions can be the most complicated ones. I also think there’s a beautiful way of writing where it’s just a pure expression of something really, really clear. I suppose what I’ve always been drawn to is an ambiguity. But a powerful ambiguity.

From what I’ve read, you have something of a background in poetry.

Yeah. My dad was a writer. Mostly nonfiction, but he did also write poetry and novels. In my house, it wasn’t necessarily music that was the big thing—it was books. My kitchen looked like this [gestures around library]. Loads of books. I was always just fascinated by books — picking them out and, like, reading them with breakfast.

What sort of books did your father write?

My favorite one is called The Book of Babel, and it’s actually dedicated to me because it came out a few months after I was born. It’s about metaphor and language. It’s a linguistics book. But it’s quite dreamy. And strange. Only looking back now, I can see that there’s elements of that that have kind of inflected the way I think about writing, especially in something like “Tomorrow Is Perfect.”

The harmonica makes the sound of the new album rich and interesting. The way you use harmonica is not something you typically hear in contemporary recordings. How did that become such a prominent part of your songs?

It’s an instrument I was aware of from a very young age because of Bob Dylan. My dad loved Bob Dylan. In terms of using it the way I’m using it now, it really just came about through playing around. I didn’t approach it from the trope of the singer-songwriter with the harmonica. I like instruments that remind us that instruments are toys. You don’t work music; you play music. Even a grand piano, or something really grandiose, it’s a toy for playing. Making music on my own, the harmonica holder and the harmonica was a way of accompanying myself that didn’t feel forced.

Your new album is your first major release since signing to A24. We’re speaking in A24’s offices right now. What made the prospect of signing with A24 appealing to you?

It was actually just the people I met. I felt like they understood where I was coming from with the music. I felt like they understood where I was at in my career. I also just felt like they were really committed to doing it straight away. A lot of the time in this industry, people are stringing people along or not being decisive or being conservative with their decision-making.

Had you experienced that sort of thing with other labels?

Yeah, a little bit, without being specific. They were the opposite of that. They were just like, “We really believe in this. We want to do it.” And the passion and energy for the music. That was my first consideration before it being A24.

Did they approach you?

Yeah. We met through [record label and management company] Scenic Route, who manage me. They knew the people here at A24. It was good timing. A24, I think, were trying to do this music thing for a while. But I think they were waiting for the right music, but also a person who was at the right point in their trajectory.

As opposed to signing an act who’s well established?

Yeah. I’m still defining my thing, and they’re obviously a new label, so they’re defining what their thing is, and it feels like a good match-up in that regard. But then, after that, I thought about the more broad context of what it means in the culture to sign to A24. And it felt really exciting. Just the freshness of it, I guess, as opposed to signing to an established indie label with its own history and its own context.

What was it about the deal that they offered that was so favorable to you?

I don’t know if I can go into that or not …

Presumably they offered you a good deal of creative freedom to do what you want to do?

Yeah, yeah. They’ve been incredibly helpful about facilitating my vision in the best way possible. Like, connecting me with people or suggesting people to work on visuals. But it’s all been quite centered around how I see it being presented. They’re really good at facilitating that. And they’re also ambitious with the vision of where it could go and what it could be.

You’re the first non-soundtrack artist to be releasing an album on A24, from what I understand. You’re at the forefront of this label, helping to define whatever it will turn into. That’s gotta be interesting and perhaps a little intimidating for you, right?

Well, it’s just music at the end of the day. By default, I take all of this incredibly seriously. I always have to remind myself it’s just music. No one’s gonna die if someone doesn’t like the album.