Researchers at the University of Buffalo could add a ‘superconducting’ twist to magnetic hard drives and random access memories (RAMs) after succeeding in building a Josephson junction using only one superconductor instead of two. The achievement could unlock new, simpler, and more flexible quantum designs in the future.

A Josephson junction is the foundational building block of quantum computers. Built on the principle of superconductivity, the device consists of two superconductor layers separated by a thin barrier. Under these conditions, the superconductive nature flows into the barrier, synchronizing their behavior.

Researchers at the University of Buffalo teamed up with those in Spain, France, and China to demonstrate that a Josephson junction could be built with just one superconductor layer instead of two and in the process showed how commonly available iron could also be used for quantum applications.

What did the scientists do?

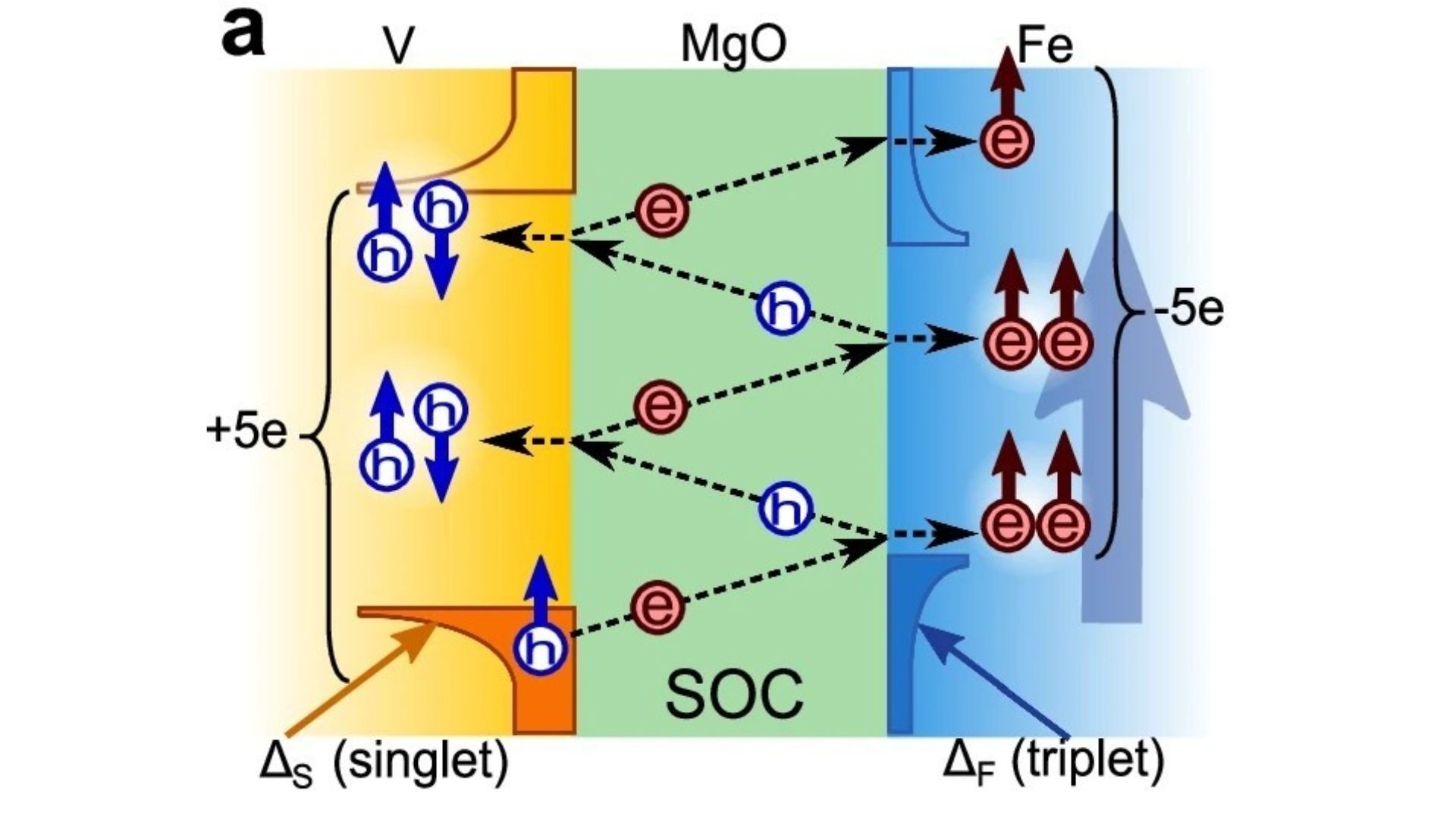

At the Autonomous University of Madrid, the researchers conducted experiments to fabricate a Josephson junction with a superconducting vanadium electrode on one side and an iron electrode on the other, with magnesium oxide as the barrier.

While superconductivity allows electrons to flow without energy loss, the flow is not continuous. Much like water flowing through a faucet appears smooth but is made up of individual droplets, continuous current is also made up of individual electrons that flow in tiny bursts.

“These small, unavoidable fluctuations in electron flow are called noise, and by listening to them we can learn how charge moves through a material,” said Jong Han, PhD, professor in the UB Department of Physics, who was involved in the work.

By analyzing the noise, the researchers measured the flow of electrons in iron and found it to be much like that in a Josephson junction.

This illustration shows how superconductivity from vanadium (yellow) is transformed at the magnesium oxide barrier (green), enabling iron (blue) to form same-spin electron pairs and participate in Josephson-junction-like behavior. Photo: Igor Žutić/University at Buffalo

This illustration shows how superconductivity from vanadium (yellow) is transformed at the magnesium oxide barrier (green), enabling iron (blue) to form same-spin electron pairs and participate in Josephson-junction-like behavior. Photo: Igor Žutić/University at Buffalo

“A typical Josephson junction with two superconductors is like two army battalions marching in step along opposite banks of a river. In our experiment, there was only one battalion — yet it’s as if its marching caused citizens on the other side to form a militia and begin marching to the beat of a different drum,” explained Igor Žutić, professor in the Department of Physics at the University at Buffalo.

Why is this important?

This behavior was unexpected because iron is a ferromagnetic substance, which is quite the opposite of a superconductor. While spins of electron pairs in superconductors are in opposite directions, those in ferromagnets are in only one direction.

Somehow, iron was able to make superconducting electron pairs, even though its spins were in the same direction. The research team does not even have a theory to explain this behavior, but is excited about its potential applications.

“The problem with conventional quantum computers is that even small environmental changes can throw off the spin of their electrons,” added Zutic. “We want to find a way to lock an electron’s spin into place, essentially, and same-spin pairing could hold some answers.”

Another added advantage of this research is that, in the future, Josephson junctions could be made from ordinary materials, such as iron and magnesium oxide. Both of these materials are commonly used in hard drives and RAMs available today.

“We have added a superconducting twist to commercially viable devices,” concluded Žutić.

The research findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.