Currently, C. auris poses a significant challenge to healthcare facilities and public health due to its ability to cause hospital outbreaks, develop resistance to disinfectants, and persist on human skin and in the healthcare environment, thereby posing a substantial threat to patient health10. C. auris can colonize the skin, respiratory tract, and urinary tract, and in immunocompromised individuals, it can cause infections in the bloodstream, respiratory tract, urinary tract, superficial wounds, and ear canal. C. auris can survive on the skin and persist in the environment, contaminating surfaces and medical equipment, leading to healthcare-associated infections through direct or indirect contact within hospital settings11,12,13,14,15. Following the principle of “early detection, early reporting, early isolation, early intervention,” C. auris cases were promptly identified based on clinical manifestations and epidemiological history, and effective contact isolation measures were implemented to prevent transmission. According to the provisional MIC breakpoints for C. auris antifungal susceptibility established by the United States of America Centers for Disease Control and Prevention16, resistance is defined as follows: fluconazole resistance at an MIC ≥ 32 µg/mL, amphotericin B resistance at an MIC ≥ 2 µg/mL, caspofungin resistance at an MIC ≥ 2 µg/mL. Nevertheless, according to the recently updated European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints (R > 2 mg/L), all isolates are considered susceptible to amphotericin B, provided that an elevated dose is administered17.

The CLSI has defined breakpoints for rezafungin against C. auris, while breakpoints for other antifungals remain undefined. Reported MICs of amphotericin B for C. auris vary substantially across antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) methods. Although CLSI and EUCAST reference methodologies yield the most reliable results, they are labor-intensive and impractical for routine clinical laboratories, which often rely on commercial assays such as Vitek 2, Sensititre YeastOne (SYO), and Etest18. Despite its convenience, SYO has notable limitations in testing C. auris. Studies demonstrate that SYO frequently overestimates amphotericin B resistance when colorimetric MICs are interpreted according to the provisional the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention breakpoint of 2 mg/L. Compared with the CLSI reference method, SYO produced MICs one to two dilutions higher, resulting in major error rates of up to 89%19. Reliable AFST is essential for guiding antifungal therapy, and amphotericin B MICs should preferably be determined using reference methods. When identification results are uncertain, additional confirmatory approaches are warranted. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry has demonstrated high accuracy for the identification of C. auris20.

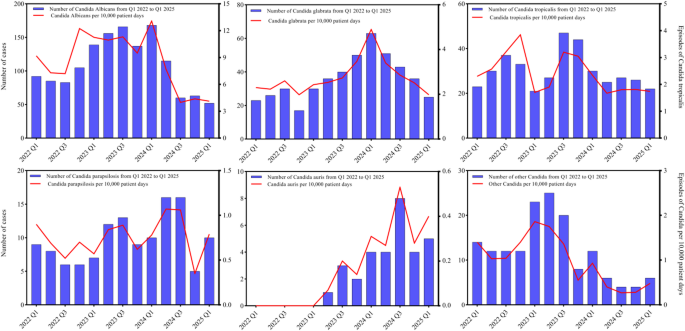

According to published reports, the fluconazole resistance rate of C. auris in China was 98.72% (308/312) [8]. The MIC values for 5-flucytosine were all < 0.25 µg/mL, and the resistance rate to amphotericin B was 4.17% (13/312)8, In this study, the fluconazole resistance rate of C. auris isolates from the hospital was 77.42%, and the resistance rate to amphotericin B was 3.23%, which are slightly lower than those reported in the literature. This discrepancy may be related to regional differences within China, given its vast geographic range and north-south variations. The increasing prevalence of infection caused by non-albicans Candida species is associated with the widespread use of prophylactic antifungal agents such as fluconazole21, however, the emergence of C. auris does not appear to be directly related to the overall antifungal drug usage in hospitals3, Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand the impact of antifungal drug use and stewardship on the susceptibility of C. auris. These findings also underscore the continuing critical role of infection control measures in preventing the nosocomial transmission of C. auris22,23.

The risk factors for C. auris infection are similar to those associated with infections caused by other Candida species24, approximately 10% of patients colonized with C. auris develop invasive infections, particularly those in intensive care unit settings who require mechanical ventilation and have invasive devices in place12,13,25,26. The crude mortality rate of C. auris infection ranges from 0% to 72%23. This study also found that the mortality rate associated with C. auris was higher than that of other Candida species. Therefore, strategies to prevent the nosocomial transmission and outbreak of C. auris infections in hospitals must be established27,28,29. These include identifying patients with C. auris infection or colonization, implementing surveillance and reporting systems for C. auris infections, and performing species-specific identification of Candida isolates from sterile body fluids in all suspected invasive infection cases. Microbiology laboratories should promptly report findings to the hospital infection control department or the designated infection management team, as well as provide feedback to the attending physicians. Upon receiving such reports, the infection control department should conduct epidemiological investigations and implement contact isolation measures to prevent further transmission30,31. Active screening and isolation should be conducted for patients with a history of close contact with C. auris, as well as for patients and their close contacts or suspected colonized individuals in facilities with a high number of C. auris cases. Screening should include sites such as the axilla, groin, and other relevant locations (e.g., urine, throat, wounds, and catheters)15. Patients with C. auris infection or colonization should be isolated in single rooms with dedicated bathrooms whenever possible. Alternatively, patients infected or colonized with the same organism may be cohorted in multi-bed rooms. Group nursing care, similar to that used for patients with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infection or colonization, is also recommended. Due to the slow growth and low sensitivity of traditional culture methods, PCR-based assays or metagenomic next-generation sequencing techniques can be employed when available32,33. Regular assessment of colonization and decolonization status in C. auris patients is recommended. Some reports indicate that twice-daily skin decolonization using disposable towels (wipes) soaked in 2% chlorhexidine gluconate or 4% chlorhexidine solution can reduce colonization. For patients on mechanical ventilation, oral rinsing with 0.2% chlorhexidine may also contribute to decolonization to some extent12.

Due to biofilm formation, C. auris can survive on various environmental surfaces for several weeks and has been isolated from healthcare workers’ hands, nasal cavities, and groin areas. This may serve as a source of transmission to other hospitalized patients34. Therefore, healthcare workers must strictly adhere to hand hygiene protocols and use appropriate personal protective equipment. Isolation gowns should be worn during invasive procedures, extensive patient contact (such as repositioning or bathing patients), or when handling patient excreta. Visitors should also follow corresponding isolation measures, including wearing gowns, performing hand hygiene, and wearing gloves. Routine cleaning and disinfection of the environment and surfaces should be performed at least twice daily. Since quaternary ammonium disinfectants (e.g., benzalkonium chloride) have limited efficacy against C. auris, chlorine-based disinfectants at a concentration of ≥ 1000 mg/L should be used 2–3 times daily for effective decontamination35. However, high concentrations of chlorine-based disinfectants can be irritating and may cause corrosion of medical instruments and equipment36,37.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this study did not analyze the antifungal susceptibility of C. auris to micafungin and anidulafungin. Due to their favorable safety profile and efficacy, echinocandins have become the first-line treatment option for C. auris infections38. The hospital is currently advancing and improving echinocandin susceptibility testing, with further analysis and research planned. Second, this study did not investigate the relationship between resistance trends in other Candida species and C. auris, which warrants further investigation in future studies. Third, we acknowledge that the relatively small number of C. auris cases included and the absence of molecular epidemiology limit the depth and generalizability of our analyses. Nevertheless, given that C. auris has only recently emerged in our region, systematically documenting its clinical characteristics, antifungal susceptibility patterns, and patient outcomes provides timely and clinically meaningful insights. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents one of the first observational reports on C. auris infections from our institution, thereby contributing to the limited evidence available nationally. We have highlighted this limitation in the manuscript and underscore the need for future multi-center and longitudinal studies to further validate and expand upon our findings. Fourth, due to hospital data confidentiality and the need for additional ethical approval, AFST data for other Candida species and detailed data regarding antifungal therapy, including the specific agents administered, timing of initiation, duration of treatment, and appropriateness of therapy could not be obtained and were therefore not included in the analysis and this limitation may restrict the generalizability of the study findings. Fifth, device-related infections were reported only in aggregate, without breakdown by type, duration, or removal, and future multi-center studies or those with more comprehensive datasets could offer more detailed analyses and deeper clinical insights. Sixth, diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical and microbiological data and was not confirmed by histology of lung tissue. Finally, antifungal susceptibility testing was performed by commercial methods.