In November the company reported a record first-half net profit of $21.9 million, achieved despite subdued consumer sentiment.

Baker says Turners succeeds because it sells mid-range vehicles that people buy out of necessity rather than indulgence.

“People need cars for everyday work, so it’s not discretionary,” he says.

“When you need to buy a car, you need to buy a car.”

Despite the economy’s ups and downs over the last few years, sales have stayed pretty strong all the way through, he says.

Turners’ model is built around selling cars and capturing the finance and insurance attached to those sales.

“In those businesses, you get paid no matter what’s happening, so we know at the beginning of the year how much we’re going to make out of finance and insurance. That’s about half our business now.”

There’s also a small credit-management arm and, of course, the core used-car business.

“That’s our formula,” Baker says.

“We need to keep selling cars.”

His grounding for this formula came years earlier at Xerox and later at Ubix.

“That model is very centred around finance and service. We’ve applied those lessons to the car business, and to the best of my knowledge there’s no one else doing that.”

Turners also holds its own insurance licence, rather than farming policies out to third-party providers. Baker likens the car industry to “a bucket with holes in it”.

“Water leaks out because commissions go to finance and insurance companies. We try to keep as much of that in-house as possible.”

The company works on small margins – less than $1000 per car – but sells 3000-4000 vehicles a month.

“We’ve had five record years in a row through some pretty difficult times, and our latest first half was a record as well.

“We have a mix of annuity streams – finance and insurance – and our ‘activity’ business, which is selling cars.”

Turners’ finance book has grown from $1.6m when Baker arrived to over $500m today.

Never giving up – and knowing when to walk away

Baker has been involved in many businesses over the years, long before and after 42 Below. He says persistence is the key.

“You get lots of knocks and you’ve got to get up every time and still believe in your vision. It’s not always easy.”

But he’s also learned the importance of recognising when a venture is no longer worth the fight.

An investment in mānuka honey – through Me Today, the listed supplements and skincare company he now chairs – was hit hard by oversupply, reliance on China and Covid-era shutdowns.

“We were throwing money at it flat out and it was getting worse, not better.

“Covid saw the mānuka market tank.

“It costs you more to harvest 1kg of mānuka honey than you can sell it for.

“We pumped a lot of money into that but we had to let that part of the business go.”

Me Today continues as a supplements-focused business.

“It’s still loss-making, but it’s getting better.

“We’re working hard on it, and I think it’s got big potential.”

The company’s 2025 annual report included 12 months’ trading of the King Honey business together with the Me Today brand and the agency business The Good Brand Company, reporting a group loss of $6.02m.

In July, King Honey – which had been ring-fenced from Me Today – went into receivership.

Zigging when others zagged

Baker’s tie-up with Turners began in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis, when about 75 New Zealand finance companies collapsed.

“I’ve always believed in zigging while others zag. Everyone was out of business, but there was still going to be a need for a finance company. So we bought 20% of Dorchester.”

The late Hugh Green also held about 20%.

“Hugh said, ‘Every dollar you put in, I’ll put in a dollar.’ And he did.”

Dorchester grew, but Baker and his partners realised the difficulty of securing consistent loan origination. The answer was to own the point where customers start their car-buying journey.

“We thought we should be in the car-dealing business so we could control origination. We bought a small stake in Turners from Milford – about 20% – put someone on the board, and eventually bought the whole thing.”

Turners’ market capitalisation today is around $729m.

“We paid $400,000 for a 20% stake back then, valuing it at $2m. Now we’re firmly in the mid-cap space.”

42 Below – the audacious punt

Few people know Baker and high-profile businessman Eric Watson were partners long before 42 Below, and even worked together at Xerox.

Watson later founded Blue Star Group, where Baker became chief executive.

Baker’s 7% stake in that business was his first break when it sold – resulting in a cash injection and allowing him to do other things.

After a series of smaller ventures, Baker and his partners wanted to build something with scale.

Then came future 42 Below partner Geoff Ross, who was brewing vodka in his garage.

“It was a good-quality product, selling in small quantities. Geoff saw that the global vodka market was huge, and New Zealand’s was tiny.”

Baker and partners invested $2m for nearly half the company.

“It doesn’t seem like much now given what we sold it for, but at the time it was a lot for a business turning over a few hundred thousand.”

Their strategy was simple: chase market share, not profit.

“It was a software-type model – put all the money in up front and it takes care of itself later.”

When they needed more capital, they took the audacious step of listing on the NZX with a market cap of $60m.

While younger investors loved the idea, traditional bankers hated it.

Baker says NZX chief executive at the time Mark Weldon was supportive, seeing the stock exchange as a place to raise growth capital, and the company listed in 2003.

Three years later, 42 Below received a takeover offer from Bacardi Ltd at 77c per share, valuing the company at $138m.

The cash offer was at a 35% premium to the market price of 57c. The stock has traded between 48c and 71c in the last year.

Scented candles to skincare – the Trilogy play

After 42 Below, Baker helped build what would become Trilogy – which he says was ultimately a bigger financial success than the vodka start-up.

It began with a small investment in a candle-making business run by an Australian airline pilot filling in time between flights.

“He was making fragrant candles in his garage. It kept getting bigger, so we took a stake. Then it got too big for him.”

They applied the 42 Below formula: invest more, list the company, raise capital.

“Scented candles became a thing.”

Ecoya listed on the NZX in 2010 but Baker said the company needed something else.

To accelerate the business, Baker sought acquisitions.

Trilogy – founded in 2002 by Wellington sisters Sarah Gibbs and Catherine de Groot – was turning over $10m and came up for sale.

Baker’s group bought it for $18m, rolled their candle business into it, and later added other skincare brands such as CS&Co and Lanocorp.

The company grew to $150m in turnover – bigger than 42 Below – and profitable because of higher margins.

Ecoya became Trilogy in 2013, reflecting the greater contribution to the business that skincare was making.

Later – within a week of each other – two potential acquirers approached: China’s Citic, and a large pharmaceutical company.

Citic ultimately bought the company for around $205m in 2018.

Hits and misses

Baker describes other investments as “long shots that mostly turned out okay”, including a stake in early mobile-marketing firm Hyperfactory, founded by Derek Handley and his brother.

“It was before iPhones. They were making mobile sites and doing mobile advertising. It had potential, but needed more cash and deeper expertise than we had.”

They eventually sold their 30-40% stake to US publishing company Meredith.

Then there was energy retailer Empower, which was sold to Contact Energy in 2000 for $23m.

Over time, Baker has developed an instinct for when a business can be made to work – and when it needs to pivot.

“You go in with an idea, but you have to be prepared to change. Turners is a good example.

“When we bought in, it was an auction business.

“Now it’s virtually no auctions – just an integrated car dealer.

“You can’t stick rigidly to a vision.

“You have to find the opportunities you didn’t expect.”

Naysayers and imagination

New Zealand, Baker says, has no shortage of sceptics.

“People don’t have a lot of imagination. They just want to look at all the ways something won’t work.”

One of 42 Below’s biggest detractors was Devon Funds’ Paul Glass.

Baker notes with irony that Devon Funds had just bought half a million of his shares in Turners, the $3.8m in funds from which he will be spending on his next Ferrari.

“It’s quite funny how that worked out.”

Baker points to Xero founder Rod Drury and Xero as someone who backed himself despite early criticism.

“When we listed 42 Below, Rod came to see Geoff and me to ask how we did it.

“If you look at his listing, he did exactly the same thing – pre-listing valuation of $60m, sold 25%, raised $15m.”

Xero also had a poor reception at first, trading around 40c a share.

Today it trades on the ASX at A$118 ($135) a share.

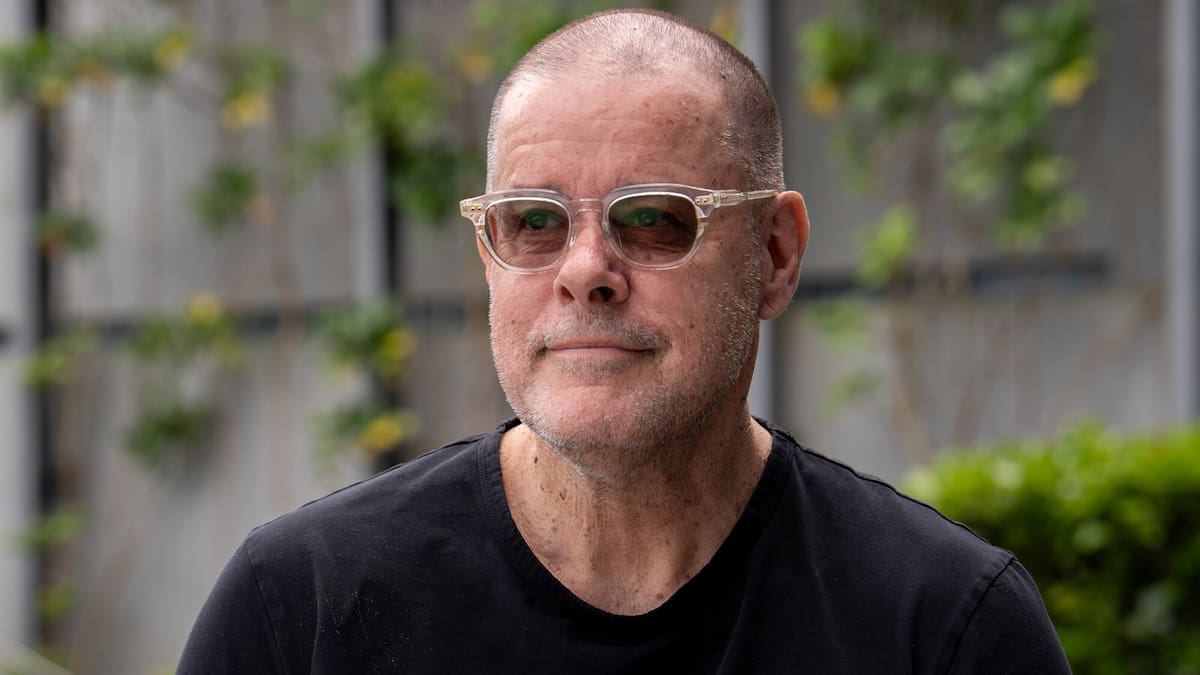

Grant Baker with his Ferrari Enzo. Photo / Suppied

Ferraris – the expensive habit

Baker admits one reason he still works so hard is his long-running Ferrari addiction. He has owned nearly 50; he currently owns 10.

“It’s an expensive hobby and I need to feed it.

“Ferrari has range cars that anyone can order, but the best cars – limited editions – only go to people who’ve done their apprenticeship buying the range cars.”

He has also done “a reasonable amount” of motorsport and has backed rising New Zealand Formula One talent Liam Lawson.

“He’s definitely fast enough. Very, very good.”

Baker long ago stopped caring about criticism.

“I used to get a lot of stick, but not anymore.”

He’s not on any other boards, and wouldn’t want to be.

The key to surviving in entrepreneurship, he says, is simple: “Make your successes bigger than your failures.”

And he often recalls advice from a favourite uncle: “Don’t be too crushed by your failures.”

Jamie Gray is an Auckland-based journalist, covering the financial markets, the primary sector and energy. He joined the Herald in 2011.

Stay ahead with the latest market moves, corporate updates, and economic insights by subscribing to our Business newsletter – your essential weekly round-up of all the business news you need.