Nick Cave’s musical foil. Decorated soundtrack composer. Wildlife sanctuary founder. Ahead of two Aotearoa NZ Festival of the Arts performances, Warren Ellis talks with Russell Baillie.

On this London evening Warren Ellis presents himself in Zoom close-up, his Father Time beard disappearing out of the bottom of frame. Near

the top, his psychedelic baseball cap’s peak is ringed with metal clips. Maybe they’re part of some inexplicable personal grooming regime. But at certain angles it can look like a mad scientist’s device, those clips just needing wiring up to a lightning rod on the roof.

Not that his brain needs the extra voltage right now.

“I woke up at 1.50pm, which I haven’t done since the 80s when I was a heroin addict and alcoholic, and I had a sense of disgust but I was also proud of myself,” he offers by way of a disarming introduction. “And here we are.”

A few minutes in and we’ve already covered the highlights of his short day. There’s been some dog walking. There has been watching the world record attempt of massed bagpipes playing AC/DC’s It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ’n’ Roll) from Melbourne. He found it incredibly moving, which is understandable perhaps for an Australian whose speciality has been applying unlikely instruments – violin, mostly – to the gothic-gospel rock ’n’ roll of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, the biggest name coming to the Aotearoa New Zealand Festival of the Arts next month. But it’s also to do with it being a tribute to original AC/DC singer Bon Scott, who played a bagpipes intro on the song released 50 years ago.

Ellis, one senses, is a man who loves rock history in its minutiae and mythology. After all, a discussion about NC&TBS’s latest of many live albums, Live God, becomes a discourse on his live album favourites (for the record, they include works by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Sid Vicious, Jerry Lee Lewis). Additionally, his ventures into music antiquity have included recording two albums with the late Marianne Faithfull.

Watch Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds from their Live God show in Paris.

He wrote a rollicking memoir in 2021 entitled Nina Simone’s Gum, sparked by taking a lump of chewing gum and a towel she’d left on her piano as keepsakes after a London festival performance presented by Cave in 1999. More of which later.

Over 30 years, Ellis has become the right-hand man and sounding board to Cave. Which makes him kind of a cult hero’s cult hero.

But detecting the Listener isn’t quite as awed by the tartan AC/DC tribute, Ellis attempts to put us in the picture.

“I mean, I guess it’s the equivalent of you guys getting out there and doing April Sun in Cuba,” he teases. “Get your acoustic guitars and fucking jam along. So you understand what I’m talking about.” His next thought has Ellis saying he’d like to visit the grave of Dragon singer Marc Hunter when he’s in New Zealand next month. Only to be disappointed when told there’s a high chance the late, great son of the King Country is actually buried in Australia (he is). To which there’s a suggestion there needs to be a bronze statue of him in his home town and that is what I really should be writing about.

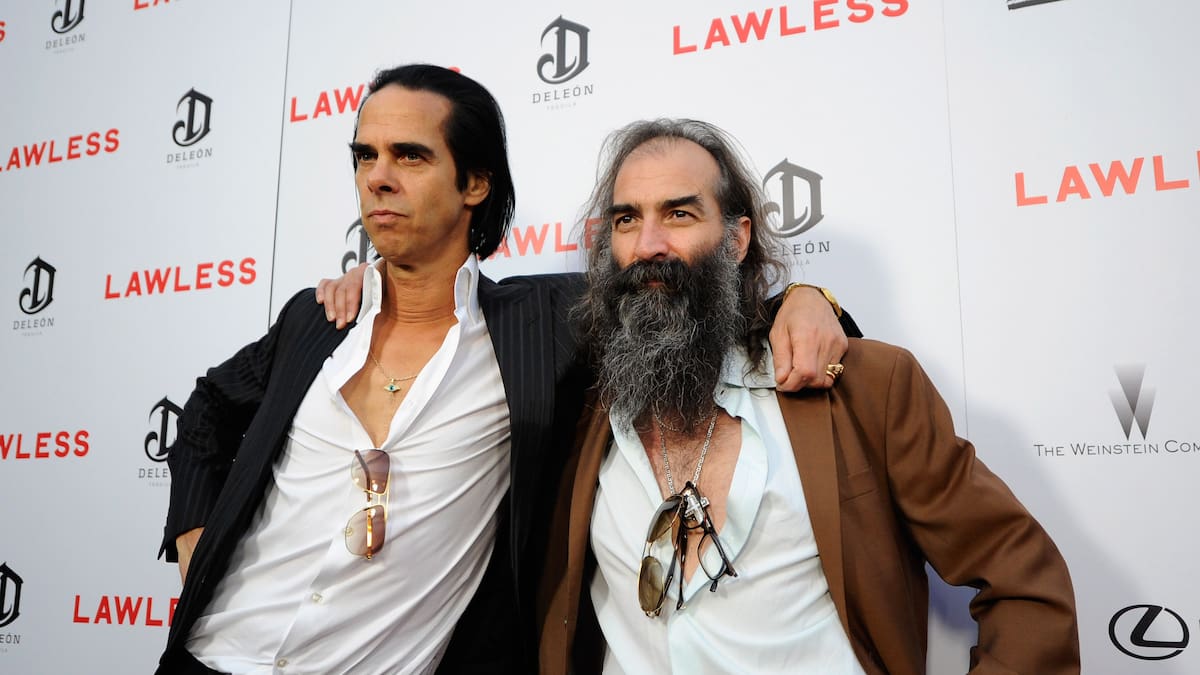

Suits you, sir: Warren Ellis in London in October. Photo / Getty Images

Yes, the Listener, unwisely perhaps, mentions the Hamilton statue of The Rocky Horror Picture Show creator Richard O’Brien, who Eliis didn’t realise was a Kiwi, but liked in a recent interview he saw. And we’re off again as he somehow connects the dots to how he’s been listening to his new copy of the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, for which the director chose pieces by Vivaldi, Mozart, Bach and Schubert, and had some of them played in slower, more bombastic arrangements. That and a sidebar on Kubrick’s regular composer and synthesizer pioneer Wendy (née Walter) Carlos.

One Warren, so many rabbit holes.

Of course, Ellis knows a few things about film music, having scored more than a dozen movies, mostly with Cave (see “Cinematic Seeds”, below) in between the dozen studio albums he’s recorded as a Bad Seed. There was also the Covid-period Carnage, the 2021 album credited to just the two of them, which captures Ellis’s airy semi-electronic arrangements without them having gone through the full-band blender.

I do have very fond memories of sitting in that hospital wondering if that was the end of my career and then getting out the next day and playing the greatest show of my life in front of, like, 20 people in some cafe.

Warren Ellis

As evidenced by the now-regular Cave backstage documentaries (20,000 Days on Earth, One More Time with Feeling, This Much I Know to Be True), the pair seem tight, a kind of veteran post-punk Jagger-Richards, if the guitarist also played violin, flute, accordion, mandolin, synthesizer and four-string tenor electric guitar.

Years ago, actor mate Noah Taylor spotted just such a guitar in a Melbourne music shop and suggested it might suit violinist Ellis. “Six strings didn’t make any sense to me, and I went down there and looked at it, and I thought I’d never play this. And I bought it, and I didn’t stop playing it.” Now, you can buy a “Warren Ellis” model guitar from a respected American maker of retro instruments.

Which isn’t bad for a guy whose first steps involved learning the accordion he’d found at the dump in home-town Ballarat where he and his brothers – sons of a bluegrass-playing and songwriting dad – hung out as kids. That was followed by a $20 fiddle, a flute, lessons, an attempted degree in classical violin in Melbourne, a period of busking across Europe and a return home to form Dirty Three. After establishing themselves as a riveting live act, the instrumental trio of himself, guitarist Mick Turner and drummer Jim White have occasionally regrouped for albums, such as 2024’s jazz-shaped suite Love Changes Everything, and tours.

The trio first played in New Zealand in the mid-1990s, a tour Ellis remembers for the possibility that he might have never gone home again. The day before the first gig at Auckland’s long-gone Kurtz Lounge, he and his bandmates went bodysurfing at Piha. He was ground headfirst into the sand, and was found unmoving, covered in blood and needing an ambulance ride to Auckland Hospital, where it was found he hadn’t actually broken his neck as feared.

“I do have very fond memories of sitting in that hospital wondering if that was the end of my career and then getting out the next day and playing the greatest show of my life in front of, like, 20 people in some cafe.”

This writer remembers the show well. Especially how Ellis stamped his boot heel into the stage with flamenco force as his violin scorched the air.

“Well, dude, I had just come back from knocking on heaven’s door. Dylan was there. I was like, ‘Fuck, Dylan was there.’ The acoustic guitars were all out, and the nurses were all singing the harmonies and next day I was in a little cafe in Auckland, living my best life. I had a few drinks that night.”

Ellis on stage in London on the Wild God tour which is headed to Wellington. Supplied/Megan Cullen

That was also about the time Cave was inviting Ellis to become part of the Bad Seeds. Cave wasn’t a total stranger. In the 1980s, Ellis flatted with a Melbourne heroin dealer to the stars. “Nick turned up, he had this kind of mystique around him,” Ellis told Spanish newspaper El País last year. “He sat in a chair and then, when he left, nobody was allowed to sit in the chair.”

It’s interesting that of all of Cave’s Bad Seeds collaborators during the years – who’ve been drawn from Australia, the UK, the US and Germany – the most productive and creative partnership is with a man of similar beginnings. Cave and Ellis were born eight years and 200km apart in Victoria country towns before heading to Melbourne for tertiary studies. Both led confrontational bands – Cave’s The Birthday Party, Ellis’s Dirty Three – that took on the world in their respective early days. Both have based most of their careers overseas – Ellis lived in Paris, where he raised a family, for 27 years. But for both, as the saying goes, you can take the boy out of Australia, but …

“There’s something that I kind of understand about the way he is, that, even though he’s a very sophisticated human being, and he’s kind of cultivated this thing, when I first met Nick and we went on a road trip, the first time we stopped the car, he just sort of whipped his clothes off and jumped into the river,” says Ellis. “That was the response of when you’ve grown up in the country. It’s like an Australian thing. So there are things within him that are beautifully Australian.”

Ellis agrees they had complementary sensibilities – Cave’s words and melodies; his sound and arrangements – which have kept their collaboration rolling.

“As long as it’s transforming and evolving in some way, then that’s fantastic. The day it doesn’t feel like it’s going somewhere that’s exciting or we’re not curious about it … I thought that day would have come a long time ago, and it hasn’t yet.”

But no, unsurprisingly perhaps, he has never offered feedback on Cave’s lyrics.

“No way. I mean, it doesn’t work like that. I don’t know enough about words. I’m a terrible reader. I’ve written a book but that just sort of happened. It’s a totally foreign kind of world for me. I’ve always loved Nick’s lyrics and stuff from before I joined the band, but I also respect that that’s his thing. It’s a big part of his thing. I’ve been in the studio 30 years with him. I don’t think I’ve ever heard anybody suggest something, because he doesn’t need it.”

Warren is essentially an ideas machine … When he is in full flight, he is unstoppable, and he is rarely not in full flight.

Nick Cave

A bit like this conversation, Ellis’s Nina Simone’s Gum started with his act of souveniring the discarded confectionery of the legendary singer and ended up somewhere else, looping back to his Ballarat childhood then forward to his strenuous efforts to make the gum an art piece to be exhibited and a jewellery mould. Where’s the gum now?

“It’s downstairs on a shelf in a box, and it’s going into an exhibition at Somerset House next year. And then beyond that, I want to find a home for it, because I just don’t want it to end up in the garbage.”

In 2024, there was another Ellis memoir of sorts – Ellis Park, a documentary by prominent Australian director Justin Kurzel about Ellis’s life and the place that now bears his name. The man who once had a monkey on his back now has primates and other creatures in his park.

Ellis Park is an animal sanctuary in Sumatra, Indonesia, that provides a home for animals, many rescued from illegal pet traffickers, which due to injuries or captivity thwarting their natural development aren’t releasable back into the wild. After meeting Indonesia-based Dutch animal welfare advocate Femke den Haas, Ellis bought the land next to her Sumatra Wildlife Centre to give the needy animals a permanent home.

Warren Ellis and the staff of Ellis Park, the wildlife sanctuary he helped establish in Indonesia. Supplied

All of which might sound like an act of rock star largesse. But Ellis sees it as another sign that neither thinking things through nor common sense have been strong elements in his career. And perhaps he’s the better for it.

“I opened an animal sanctuary. Now when I did that, I didn’t think much more about it than wanting to do something. Once I’d done it, I had no idea we had to build the fucking thing. I had no idea what was involved. If I had, it might have made me think twice about it, but I just jumped into it with my heart open.

“It’s so easy to like something on social media and think you’re doing something or raising your voice, but to actually get down and do something – taking action is the only thing that works. You can sit and shriek and complain but that does nothing.”

Cave effectively runs his own complaints department with his Red Hand Files blog and newsletter, where he’s kind of a bemused agony uncle answering fans’ correspondence, whether it’s challenging him on his religious faith or asking for career advice.

Someone asked about Ellis back in 2018, and so, as Ellis heads off on another tangent, we’ll leave the last words to the senior partner in his firm.

“Over the years, I have developed a relationship with Warren that goes way beyond a professional collaboration and we are the best of friends … There is a certain sanctity in this friendship in that it has traversed all manner of troubles over the last 20 or so years, yet remains as resilient as ever … Warren is essentially an ideas machine (anyone who has worked in the studio with him will tell you the same) and it is an extraordinary privilege to be around him, both on stage and in the studio – and anywhere else, actually. When he is in full flight, he is unstoppable, and he is rarely not in full flight.”

Cinematic Seeds

Blonde ambition: Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe in Blonde, scored by Ellis and Nick Cave. Photo / Supplied

How Ellis and Cave became go-to soundtrack composers.

The Warren Ellis/Nick Cave soundtrack business started with films by Australian directors in their circle. John Hillcoat made his feature debut with prison movie Ghosts… of the Civil Dead, which starred Cave. His next movie, To Have & to Hold, had music by Cave with Bad Seeds Blixa Bargeld and Mick Harvey. Ellis joined Cave for Hillcoat’s third, The Proposition.

When Hillcoat went to the US, he called on the pair again for his film of Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic story The Road, and then bootlegging drama Lawless. Meanwhile, another Australian director, NZ-born Andrew Dominik, tapped the duo for his Brad Pitt-starring art-western The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and gave them a musical cameo. Dominik went on to document Cave himself in One More Time with Feeling (2016) and This Much I Know to Be True (2022), before Ellis and Cave scored his polarising Marilyn Monroe biopic Blonde.

Ellis and Cave’s soundtracks have also included the Taylor Sheridan films Hell or High Water and Wind River, the Netflix television series Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, and the Amy Winehouse movie Back to Black. Their most recent was The Death of Bunny Munro, the television adaptation of Cave’s 2009 novel. Their joint scores get descriptions that suggest a tougher seven dwarfs: earthy, folky, ghostly, gritty, portentous, poignant and idiosyncratic.

Ellis, solo, wrote the score for I’m Still Here, the 2024 Walter Salles film that was nominated for a best picture Oscar. Asked what he thinks film-makers see in their music, Ellis says: “I don’t know what that is, but I don’t really want to know either, because I don’t want to destroy his idea of what it is.”

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Aotearoa NZ Festival of the Arts, TSB Arena, Wellington, February 5 & 6.

Watch Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds perform Joy from their Live God show in Paris.

SaveShare this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

Copy LinkEmailFacebookTwitter/XLinkedInReddit