David Farrar – Curia Market Research owner and manager

Firstly, some predictions:

Every poll (or almost every poll) will show that both National and Labour will need two partner parties to govern, not just one – that is: only National/Act/New Zealand First and Labour/Greens/Te Pāti Māori will have enough seats to make 61.

All 71 public polls since the election have said Labour can’t govern without both the Greens and Te Pāti Māori and only two out of 71 have National and Act able to govern without New Zealand First.

New Zealand First will continue to poll above its 2023 result. The party has been above its 6.1 percent results in the past 20 public polls.

The top three issues will remain cost of living, economy and health. These have been the top three issues in every Taxpayers’ Union–Curia poll since July 2024.

The vast majority of polls, before the campaign period, will have a narrow margin between the Government and Opposition – no bloc greater than 65 seats. No poll since November 2024 has had a bloc projected to win over 65 seats.

Key things which I will be looking out for are:

The state of the economy. I think this will be hugely influential. As well as economic data, and what the right/wrong direction polls are saying as a proxy for that.

What happens with Te Pāti Maori will also be important to keep an eye on. With the polls so close, the party’s current two-seat overhang could determine who gets to form government. But if they go into an election with new Te Pāti Māori candidates against incumbent MPs, then I think Labour will win those seats and Te Pāti Māori will not get overhang seats.

I’ll also be watching for any polls showing Labour can govern without Te Pāti Māori. This will boost Labour if they do, and damage them if Te Pāti Māori looks essential to their path to power.

How high New Zealand First rises, and whether that support is coming from former National or Labour voters is also something to watch.

Carin Hercock – Ipsos New Zealand country manager

At this stage it looks like the election will be close, rather than a big swing to one party. I say that because the last time we saw a major swing to one party was the 2020 election where Labour won 50 percent of the vote.

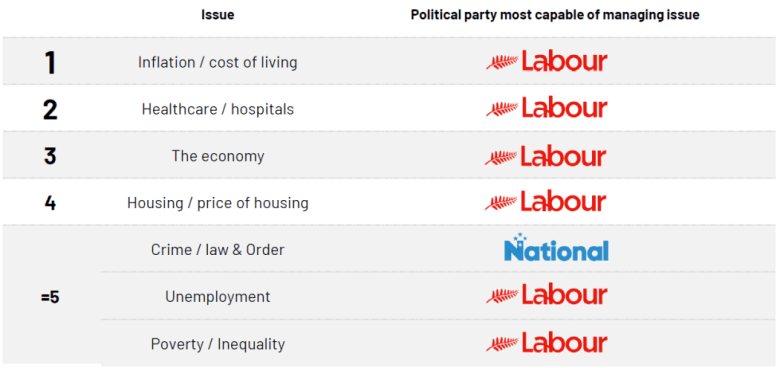

In the lead-up to that election Labour was perceived to be the party most capable of managing 18 of the top 20 issues (the Greens led on the other two) and while Labour is leading on 15 of the top 20 in our most recent survey, the gap was significantly higher between Labour and National in 2020 than it is now.

In 2020, across the top four issues, on average 22 percent more people thought Labour was more capable of managing the most important issues compared with National. In our latest Issues Monitor report, Labour’s lead is less convincing, averaging 11.5 percent and we still have almost a year to go.

In 2020, the top five issues were the economy, housing, unemployment, healthcare and poverty/inequality. Before the 2023 election, the top five issues were inflation/cost of living, crime/law and order, healthcare, housing, the economy and petrol prices (fifth equal).

In 2023, National was ahead on all the top five issues and 14/20 overall. I think the cost of living will remain a key issue in 2026. Following global trends, it should reduce as an issue, however it will take some time.

Healthcare is also likely to remain an important issue as there is no quick fix and it is the leading issue for older New Zealanders.

If the economy doesn’t see a recovery, then concerns about unemployment will continue to rise, however if the economy shows recovery, then crime may increase as an issue in the same way it did in the 2023 election.

Unemployment is a very significant issue for New Zealanders under 30 years so this could be an important issue to encourage voter turnout for younger voters.

Voters surveyed in October had greater confidence in Labour on issues relating to the economy and the cost of living

Voters surveyed in October had greater confidence in Labour on issues relating to the economy and the cost of living

The Ipsos ‘What worries the world’ monitor shows inflation has trended down as a global issue since peaking in early 2023, it is now the second-highest issue and has been overtaken by crime.

Crime may be an issue to watch next year as this is an area where National still maintains a strong lead, and the party’s recent investment in tackling the methamphetamine issue could prove to be popular.

Globally, concern around immigration control is at its highest levels for a decade and is now a leading issue for a fifth of respondents across 30 countries. Although New Zealand doesn’t have the same border issues as Europe and the United Kingdom, immigration is already starting to enter political rhetoric at home.

It’s going to be a tight race, a focus on issues and a very long campaign!

Tim Hurdle – Campaign Technologies director

Obviously, this won’t be a landslide like 2020, or a clear rejection like 2023.

The “major” parties are polling in the low-30s, which is historically soft. Where our elections have generally had the focus on National and Labour, we increasingly have left-right bloc alignment as the determining contest. And this election there will be fighting in those blocs about who has built their relative share.

Projecting an outcome is made even harder as 1-2 percent shifts will determine the government. The formula can be impacted by the “wasted” vote and the electorate seats won.

We don’t normally see big shifts in election-year polling. So, the longer-term trends are important. We can often get over-excited by the daily issues. I think the fundamental issue at this election will be an evaluation of who can present the best plan to take the economy up a gear and not stoke inflation.

There’s a consensus among pollsters and political strategists that the general election will be close. Photo: Lynn Grieveson

There’s a consensus among pollsters and political strategists that the general election will be close. Photo: Lynn Grieveson

While Prime Minister Christopher Luxon relies heavily on his quarterly performance model, the political reality is more akin to an IPO. The only date that truly matters is when he goes to the market in late 2026. Ultimately, the quarterly earnings calls are irrelevant, the voters’ decision will come down to the consolidated three-year report and his forward guidance for 2027–2029.

To win back the votes he won in 2023, Luxon must articulate how his government has delivered on the “Back on Track” promise. The new message that “National is fixing the basics and building the future” is trying to reframe the record and present it as progress toward a goal.

National also needs to win more votes from Labour to enhance the party’s chances of a centre-right government.

One poll trend this term has been the relative profiles of New Zealand First leader Winston Peters and Act leader David Seymour. We can expect their rivalry to be a feature of election year. But it remains to be seen if Peters can consistently hold this vote (tracking towards 9-10 percent).

New Zealand First will also be trying to flirt with Labour voters, while keeping their conservative base on side. They always have cultivated the ‘unhappy’ voter, and given the economy there will be plenty about.

Labour needs to establish policy credibility for people to consider the risk of change. Parties in opposition need to show that change is worth the risk. Labour has recovered from the 2023 floor, but support for Labour is soft – more a reflection of middle voters’ disappointment with the state of the economy.

Leader Chris Hipkins is currently running a ‘small target’ strategy. The aim is to let the government fail and win by default. This might prove to be a problem if the economy fires. He has also yet to find an issue that he owns and creates an alternative vision for New Zealand.

Labour is in danger of the problem the Liberal opposition had in Australia. While the incumbent government had been unpopular, when the election was called undecided voters looked and rejected the alternative. The opposition hadn’t built confidence with the electorate and didn’t look ready for government.

In 2023, Labour was roundly rejected in Auckland, with the economic downturn felt more in urban areas. National benefited in electorate battles, meaning they won seats that they hadn’t expected to. But it will be a challenge to retain some of these.

The economic situation is viewed by voters through household pressures around the cost of living. While the economic trend is vital, voters don’t judge on the GDP (gross domestic product) stats but through their discretionary income.

The 2023 election saw the continuation of the “free money” era of Covid-19 – promises that looked brave now look foolish, given the fiscal situation. It won’t be credible with voters to be making expensive promises.

Instead, parties will need to have some answers about how they can restore the government finances. This could default to an asset recycling/sales debate.

In terms of global trends that may be reflected in next year’s election:

The way we gain news has changed and people are viewing the world as the algorithm tailors it. We no longer have the shared, curated media. For example, Act voters will be seeing and hearing very different things to Te Pāti Māori voters.

This means issues can be driving different voter groups in divergent ways. The nature of the feedback loop on digital media is that it keeps serving the outrage to keep you online.

We are seeing a massive divergence between young men and young women, a trend mirrored in the United States, Australia and the UK. Young men (under 30) are breaking hard for the right (National/Act), driven by economic frustration and a rejection of “woke” cultural politics. Young women are breaking hard for the left (Green/Labour).

And issues are globalised; issues that cause outrage grab attention. Sensible and moderate positions don’t go up the search ranking.

This makes it harder for parties to campaign to win votes. They need to think of creative messaging and policy that gets through the “walls” that surround what people are being fed on their phones and tablets. We may see more micro-targeted policy as parties try to get the attention of winnable voters.

David Talbot – Talbot Mills Research director and political strategist

I should start by noting increasing international volatility so the unexpected could very well happen! That said, here are some quick thoughts:

Labour seems likely to do better in next year’s election – they’ve been above 2023 vote share in most polling.

Meanwhile, Te Pāti Māori is likely to do worse unless they manage to sort themselves out.

National will post a lower election result, compared to 2023 if Luxon can’t improve his connection with voters. I see this as a difficult ask given that public impressions seem fairly locked in on him now.

Of the fringe parties, the Opportunity Party seems best-placed, and perhaps it could make a modest run if it can find an issue that resonates.

In saying that, it doesn’t seem likely that anybody new will get past 5 percent: Act and New Zealand First have race and Trumpian territory locked up so are probably blocking the route for a right-wing populist surge, as has been seen in other countries.

Overall, the result is likely to be close. With the exception of 2023, the blocs typically are, and this picture has been pretty consistent in Talbot Mills’ corporate polling numbers.

As for potential coalitions: National seems likely to continue to need Act and New Zealand First, while Labour would likely need Te Pāti Māori and the Greens, but there’s a possibility of a two-party arrangement with just the Greens.

Barring a surprise, I think the big issues of next year will almost certainly be: cost of living, health, and economy.

The cost of living is still a critical issue around the world and “economy” means more than the macro factors (trade balances, employment, GDP) to voters, so the Government’s “turning the corner” frame might be tougher to land than some seem to predict.

The National Party is likely to go hard on a scare campaign around capital gains tax, which will misrepresent the Labour proposal.

Given the sense of a “broken promise” around last election’s tax cuts, National is unlikely to try again, especially if they need to fund those tax cuts through borrowing.