Back to Article List

While late M-stars are the easiest places to find Earth-sized planets, a new study suggests they are biological dead ends where animal life may never find enough fuel to evolve.

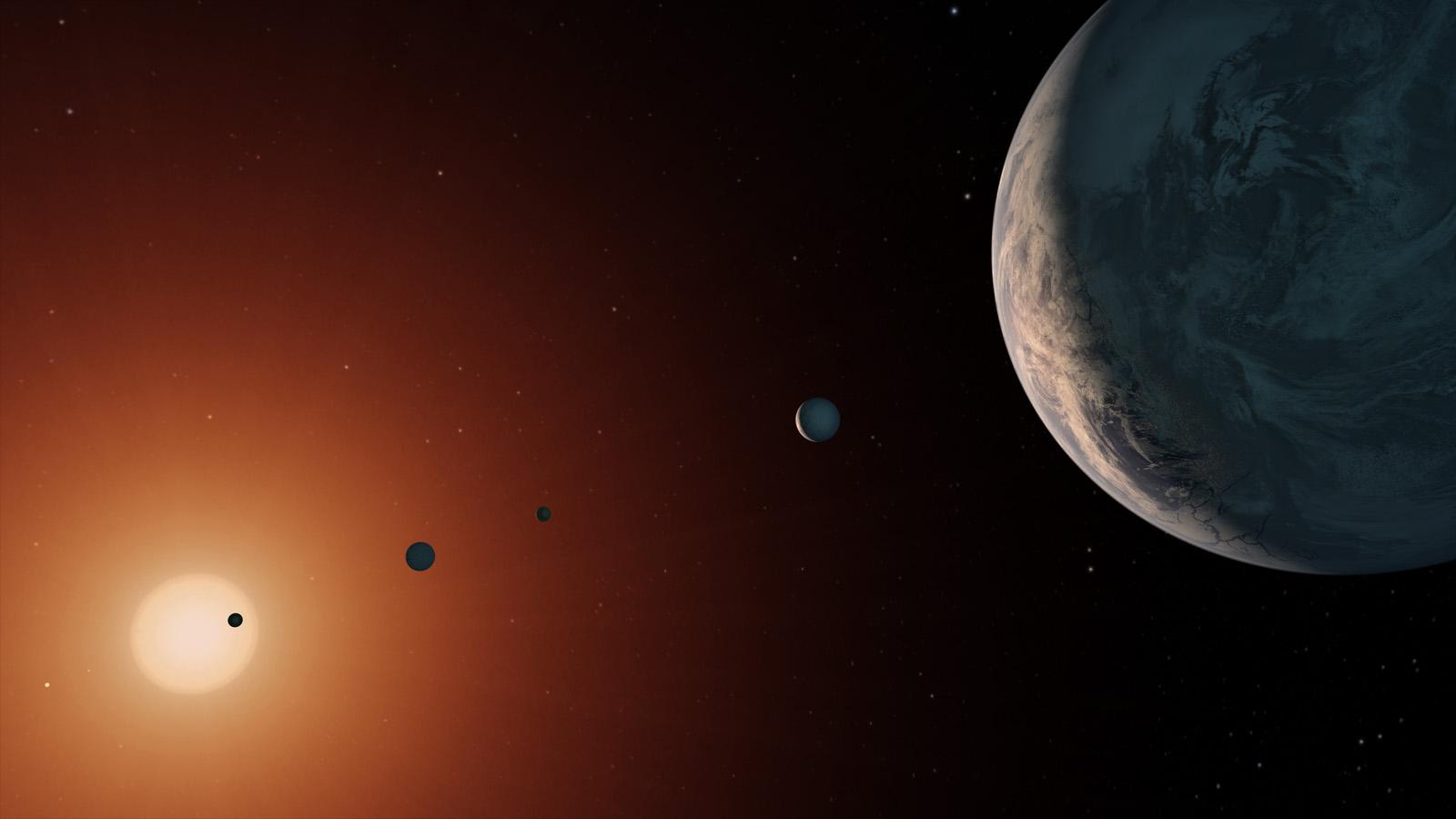

This illustration depicts the TRAPPIST-1 system from the vantage point of TRAPPIST-1f, showcasing seven Earth-like planets orbiting the late M-star TRAPPIST-1. According to a new study, stars like TRAPPIST-1 cannot support animal life. Credit: NASA

A recent study suggests that late M-stars, despite their abundance in the galaxy and potential for hosting detectable Earth-like planets, are unlikely to support the emergence of complex animal life.

This limitation stems from a fundamental mismatch between the stellar emission spectrum of late M-stars and the specific Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR, 400-700 nm) required for oxygenic photosynthesis, a critical process for atmospheric oxygen accumulation.

Simulations indicate that key biological events on Earth, such as the Great Oxidation Event and the Cambrian Explosion, would require timescales far exceeding the expected lifespan of planets orbiting late M-stars due to insufficient PAR.

Consequently, ecosystems on such planets would likely be dominated by organisms utilizing non-oxygenic photosynthesis, which can thrive on the abundant longer-wavelength light, thus precluding the widespread oxygen accumulation necessary for complex, animal metabolisms.

Humans are captivated by the idea of finding life elsewhere in the universe – and even more by the idea that life, if found, might resemble the complex, animal life here on Earth. One of the easiest places to look for Earth-like planets that could potentially be home to animal life is in the orbits of M-stars, the most prevalent stars in our galaxy. However, according to a new study posted to the ArXiv preprint server, a specific subset of these — the smallest and coolest known as late M-stars — are not capable of developing animal life.

The problem, as Bill Welsh, astronomer at San Diego State University and study co-author, explained in a Jan. 7 press conference at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, is a fundamental mismatch between the light these stars emit and the light animal life needs to produce oxygen. If the study’s findings are true, the hunt for extraterrestrial animal life just got a lot harder, as late M-stars yield the most detectable Earth-like planets and make up 35 percent of all stars in the galaxy.

Welsh and Joseph Soliz, study co-author, conducted a deceptively simple thought experiment. Instead of guessing what the alien biology of a world orbiting TRAPPIST-1 might be like, they asked a different, yet related question: “What would happen if we put Earth in orbit around TRAPPIST-1?”

On Earth, the “Big Bang of biology,” as Welsh called it, was the Cambrian Explosion, a flood of complex animal life that happened about 500 million years ago. That explosion was only possible because of a long build-up of oxygen known as the “Great Oxidation Event” (GOE) — the critical period roughly 2.3 billion years ago when oxygen first began to accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere. This process started 2.5 billion years before the GOE with the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis, which began releasing an increased amount of oxygen into Earth’s atmosphere.

Oxygen is the best fuel source for complex, animal life. Organisms with aerobic (oxygen-based) metabolisms generate energy far more efficiently than organisms with anaerobic metabolisms.“Oxygen is a very reactive molecule,” Welsh explained. “Oxygen provides roughly a factor of 16 times more energy if you use oxygen in your metabolism than if you don’t,” he continued. This efficiency creates an abundance of spare energy that a lifeform can use to develop “shells and appendages and all kinds of things that animals need.” Welsh said. Without oxygen, scientists believe life is limited to what Welsh described as “small sub-centimeter type life.”

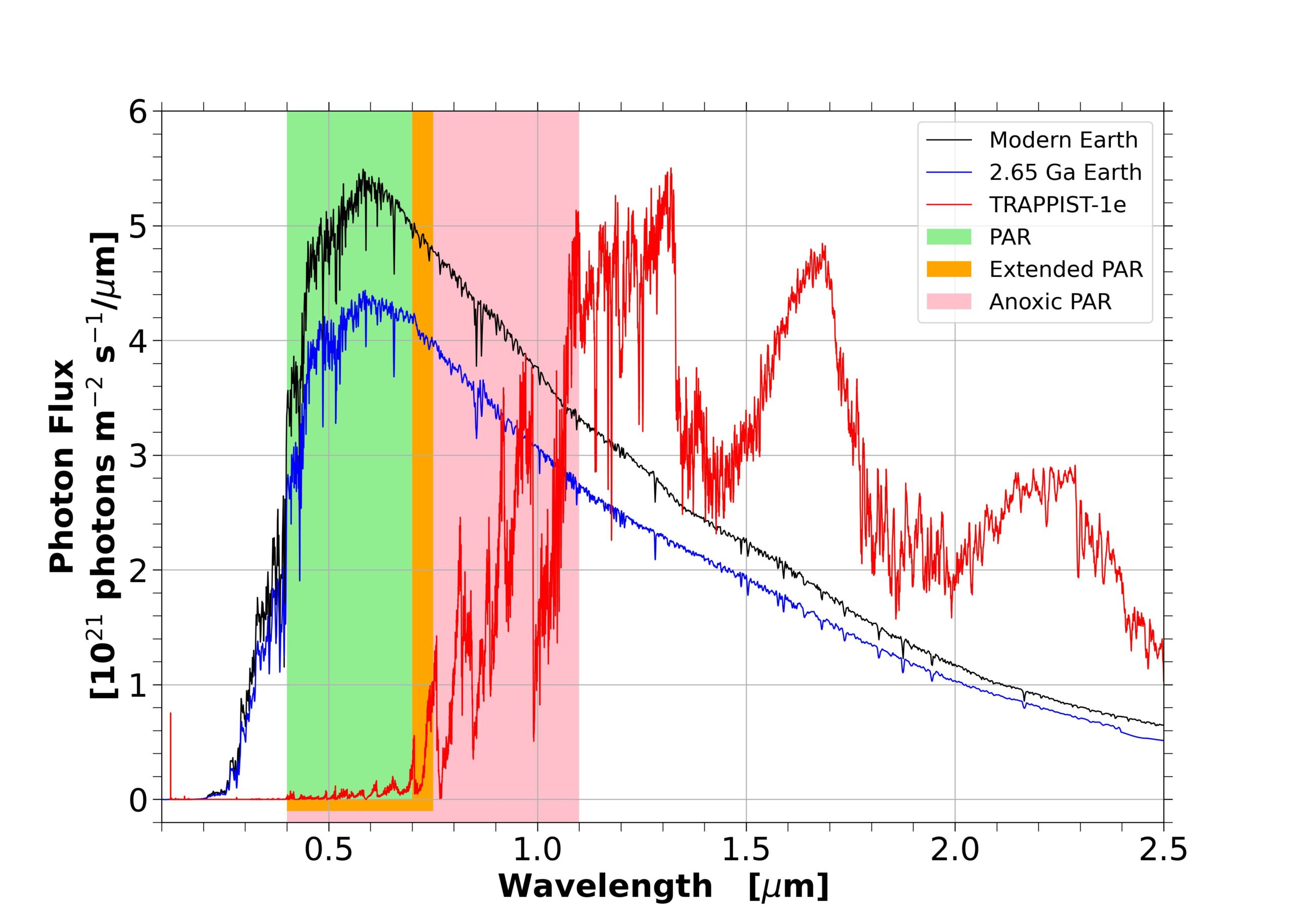

But oxygenic photosynthesis is also a picky eater. It requires Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) — light in the 400- to 700-nanometer range. On Earth, our Sun provides a feast of these photons. Around a late M-star like TRAPPIST-1, however, it’s more famine than feast. TRAPPIST-1 provides hardly any photons in this range. Instead, the star’s energy is focused almost entirely above the 800-nanometer range.

This graph compares the amount and wavelength of light reaching modern Earth, ancient Earth, and the exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e. The green shaded area marks the specific light ranges required for oxygenic photosynthesis, and the red shaded area marks non-oxygen-producing photosynthesis. Credit: Soliz, J. J., & Welsh, W. F. (2026). https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.02548v1

In the dim, red glow of TRAPPIST-1, a hypothetical Earth would receive less than one percent of the PAR photons it gets from our Sun. According to the study, the GOE that took 700 million years on Earth would take 63 billion years on an Earth orbiting TRAPPIST-1. And a Cambrian Explosion would take a staggering 235 billion years.

“What happens 100 billion years from now is a whole heck of a lot of speculation,” Welsh said at the press conference. “We’re limited to the Big Bang and in that time scale, we don’t expect such planets to harbor life.”

But there is a second, perhaps more decisive blow to our hopes for alien neighbors. While oxygen-producers are starved for light on late M-stars, another group of organisms is enjoying a free lunch. Non-oxygenic photosynthesis — the kind used by less complex organisms — is far less picky. It can harvest the photons that M-stars produce in abundance.

“Non-oxygenic microbes will have a huge advantage,” Welsh said at the press conference. “They’re probably going to dominate the ecosystem.”

“We expect that there will be life on these stars for sure, but it might look like … purple bacteria living in a sulfur pool, just scratching out an existence,” Welsh tells Astronomy. Without oxygen, he explains, it is unlikely we will ever find anything advanced enough to talk back. “It’s kind of a bummer because we’re talking about something like 35 percent of all stars in the galaxy.”