Credit: ZME Science/Carnegie Mellon University, Sankaranarayanan et al, 2025.

Credit: ZME Science/Carnegie Mellon University, Sankaranarayanan et al, 2025.

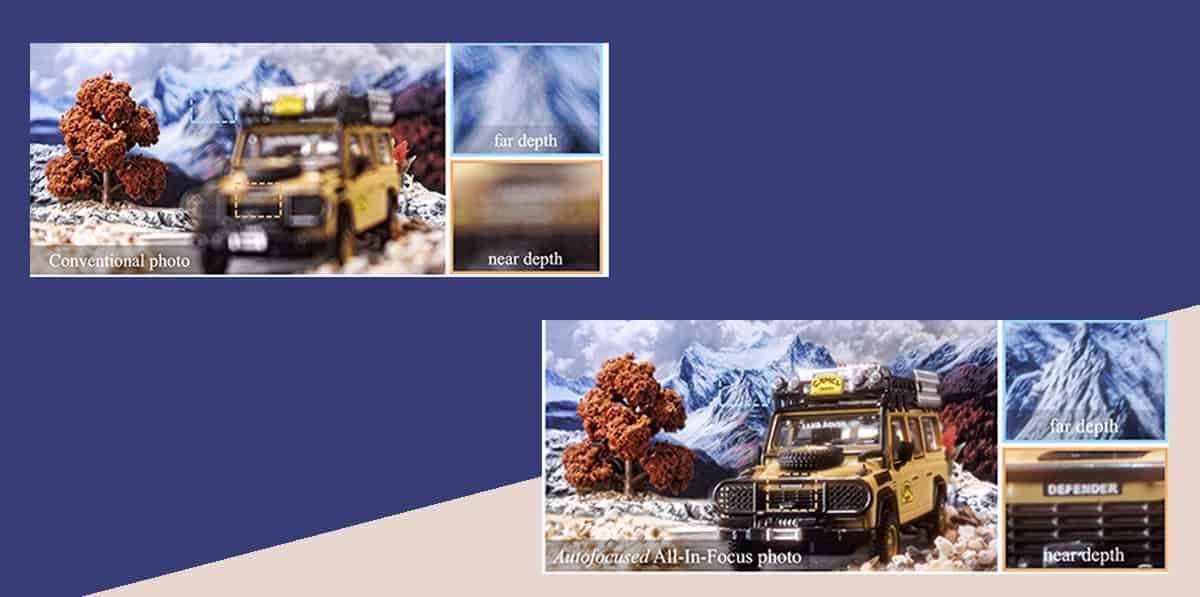

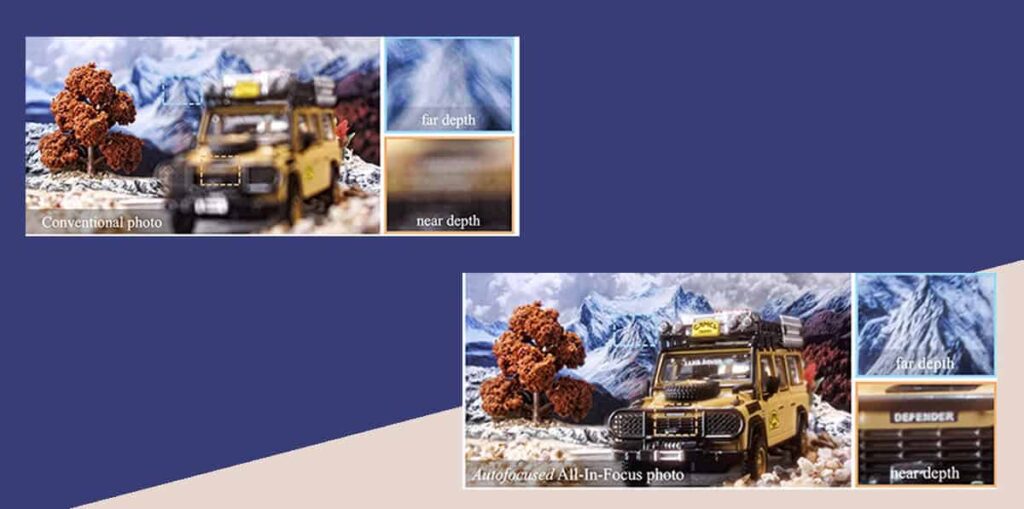

For more than a hundred years, cameras have shared a frustrating limitation with human eyes: they can only focus on one distance at a time. Photographers learned to live with blur, turning it into an artistic choice or working around it with careful staging and patience.

Now a team at Carnegie Mellon University has built a camera that simply opts out of that trade-off. Every part of the scene snaps into focus at once, no matter how close or far away it is.

The result feels a little uncanny. A flower inches from the lens and a mountain on the horizon both look crisp, as if the laws of optics briefly loosened their grip. But this is not a software trick or an AI illusion. The sharpness happens in the lens itself, as light enters the camera.

“Our system represents a novel category of optical design,” says Aswin Sankaranarayanan, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. “One that could fundamentally change how cameras see the world.”

Credit: Carnegie Mellon University.

Why Blur Has Always Been Part of Photography

Classic camera lenses focus light onto a flat sensor. Only objects sitting on a specific plane (the focal plane) appear sharp. Anything closer or farther turns soft. Photographers can adjust the aperture to bring more of the scene into focus, but that reduces light and introduces diffraction, a different kind of blur caused by physics itself.

Another workaround is focus stacking. You take many photos at different focus distances and merge them later. Macro photographers often rely on this technique. It works beautifully — until something moves. People, animals, leaves in the wind, or a camera mounted on a moving vehicle all break the illusion.

Light-field cameras promised a solution a decade ago by capturing directional information about light, allowing focus to be adjusted after the fact. But those systems sacrifice resolution and still rely heavily on computation.

So, all this time, optical engineers have circled the same question: could a lens focus on more than one depth at the same time?

“We’re asking the question, ‘What if a lens didn’t have to focus on just one plane at all?’” says Yingsi Qin, a Ph.D. student in electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. “What if it could bend its focus to match the shape of the world in front of it?”

A Lens that Adapts Pixel by Pixel

The complex system employed by the researchers. Credit: Carnegie Mellon.

The complex system employed by the researchers. Credit: Carnegie Mellon.

The Carnegie Mellon system does exactly that. Instead of setting one global focus distance, it changes focus across the image itself. One region can lock onto something nearby, another onto something far away, simultaneously.

Matthew O’Toole, an associate professor of computer science and robotics at CMU, describes it this way in The Verge: the technology “let[s] the camera decide which parts of the image should be sharp — essentially giving each pixel its own tiny, adjustable lens.”

At the heart of the system is what the researchers call a “computational lens.” It combines two key pieces of hardware. The first is a Lohmann lens (also known as an Alvarez lens), made from two curved, cubic plates that slide against each other to change focus. On its own, this lens adjusts focus for the entire image.

The second component is a phase-only spatial light modulator, or SLM. This device controls how light bends at each tiny region across the image. By coordinating the Lohmann lens with the SLM, the camera can focus different parts of the scene at different depths, all in one exposure.

This setup produces what the researchers call a freeform depth of field. Instead of a flat slice of focus, the focal surface can curve and twist to follow the actual geometry of the scene.

Teaching a Camera to Know What Should Be sharp

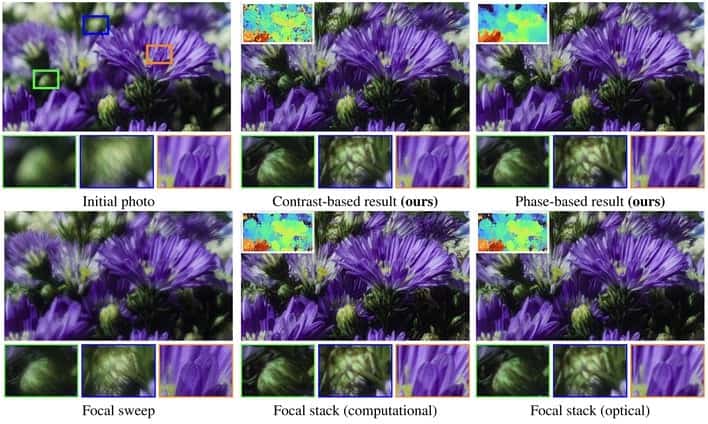

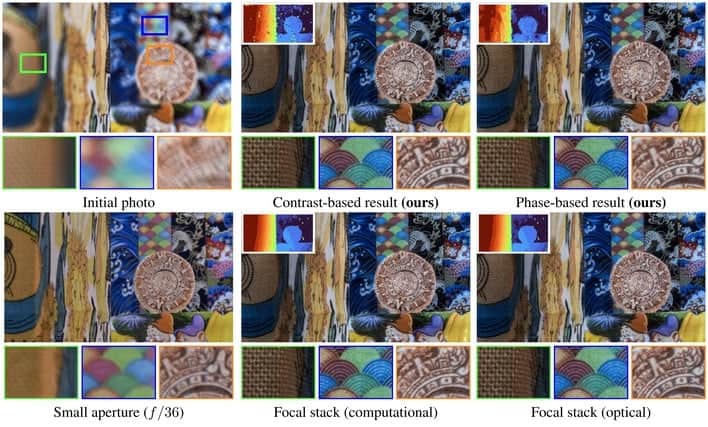

Of course, the camera still needs to know where things are in space. To figure that out, the team adapted two familiar autofocus techniques and applied them locally across the image.

The first is contrast-detection autofocus. The camera divides the image into small regions and nudges focus until each region becomes as sharp as possible. The second is phase-detection autofocus, which compares tiny differences between paired pixels to determine not just whether something is out of focus, but which direction to adjust.

The prototype uses a Canon EOS R10 with a Dual Pixel CMOS sensor, which allows every pixel to participate in phase detection. That hardware choice lets the system work fast enough for real scenes. According to the researchers, the camera reaches 21 frames per second.

“For the first time, we can autofocus every object, every pixel all at once,” Qin says.

Crucially, the final image requires no post-processing. The sharpness is optical, not computational. That distinguishes this system from light-field cameras and AI-based sharpening tools, which often introduce artifacts or reduce resolution.

What this Changes — and What It Doesn’t, Yet

Right now, the camera exists as a bulky prototype built in a lab. It is not something you can buy, and it may never look like a conventional camera. The system is also inefficient with light, which limits performance in dim conditions.

Still, the system could prove highly useful beyond photography.

Microscopes could use similar optics to capture thick biological samples entirely in focus, instead of scanning through layers one plane at a time. Machine-vision systems could inspect complex objects without worrying about depth. Autonomous vehicles could see cluttered environments more clearly, without guessing what might be blurred away.

Virtual and augmented reality systems might benefit too. Human vision does not experience depth of field the same way cameras do, and mismatches can cause discomfort. A display system that shapes focus more like the real world could feel more natural.

The researchers also note that the system can intentionally shape focus, not just eliminate blur. It can mimic tilt-shift effects, selectively blur objects, or even optically ignore thin obstructions like wires by focusing past them.

This work fits into a broader trend in imaging science: merging optics and computation instead of treating them as separate stages. Rather than capturing a flawed image and fixing it later, engineers increasingly design cameras that make smarter choices at the moment light enters the system.

Sankaranarayanan claims this is not just a better camera trick. It is a new way of thinking about what a lens can be.

The researchers presented their findings at the 2025 International Conference on Computer Vision and received a Best Paper Honorable Mention recognition.