Key Insights

Most of today’s quantum computers rely on qubits with Josephson junctions that work for now but likely won’t scale as needed for applications.

Researchers are focusing on improved junction materials, but integration requires further study.

The industry remains committed to traditional junctions because alternatives underperform, but that commitment leaves the problem unsolved.

Quantum computers could be chemistry’s next big tool, helping researchers run ever more complex simulations, model molecules, and design new materials from first principles. But some researchers believe that vision is unlikely to materialize without breakthroughs made by the very chemists and materials scientists that quantum computing hopes to serve.

Despite steady progress, today’s quantum computers remain far from tackling the applications they promise. The challenge is scale: performing useful calculations will require machines with millions of quantum bits, or qubits, which are the building blocks of quantum computers. But progressing from devices with hundreds or thousands of qubits to ones with millions exposes a weak point that has long been accounted for via design work-arounds rather than solved—Josephson junctions and more specifically, the materials these critical contraptions are made of.

At the heart of today’s most advanced quantum computers sits a device called a Josephson junction. “The Josephson junction is the transistor of quantum computing,” says Kin Chung Fong, an engineer at Northeastern University, Burlington. In simple terms, that term describes what a Josephson junction is—a quantum switch that, like a transistor, turns on and off repeatedly. When fashioned into a special circuit, it enables the circuit to store and manipulate quantum information.

Some researchers are now voicing concerns that the materials used by nearly the entire quantum computing industry, including Google and IBM, to build these junctions may not scale to the large, stable machines required for real-world applications. “If you want to make millions of qubits on a single chip,” says Julian Steele, a physicist at the University of Queensland, “the qubits will have to go through something similar to the materials revolution that transistors went through in the fifties.”

In a Josephson junction (left), electrons tunnel through the insulating barrier. This unusual quantum process is like a ball disappearing from one side of a mountain and suddenly appearing on the other side without having traversed the mountain.

Credit:

Yang H. Ku/ Will Ludwig/C&EN

Why do we need Josephson junctions?

Josephson junctions reside in the most common version of quantum machines used today, ones known as superconducting quantum computers. Superconductors are materials that carry electric current with no energy loss when cooled to extremely low temperatures. Each junction consists of three layers, with two superconductors sandwiching an ultrathin insulating barrier.

Ordinarily, the insulator would block electric current from flowing through. But because the barrier is only a few atoms thick, electrons can cross it by quantum tunneling—a process that enables particles to appear on the other side of a barrier without physically crossing it. It is as if a ball resting on one side of a mountain vanishes and instantly reappears on the other side without having gone over the mountain.

“The Josephson junction is the transistor of quantum computing.”

Kin Chung Fong, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, Northeastern University, Burlington

This strange tunneling phenomenon is typical of the odd quantum behavior that governs the actions and properties of the tiny particles that make up everything.

In Josephson junctions, tunneling occurs only under specific circumstances. The process depends on the phase of the superconductors. The phase is a property that describes the collective motion of the electrons inside the superconducting material and can be thought of as a wave. When the waves align in just the right way, tunneling can occur; when they are out of alignment, tunneling can’t happen, and current flow is suppressed. When these junctions are placed in a superconducting circuit, this phase property is what turns them into qubits.

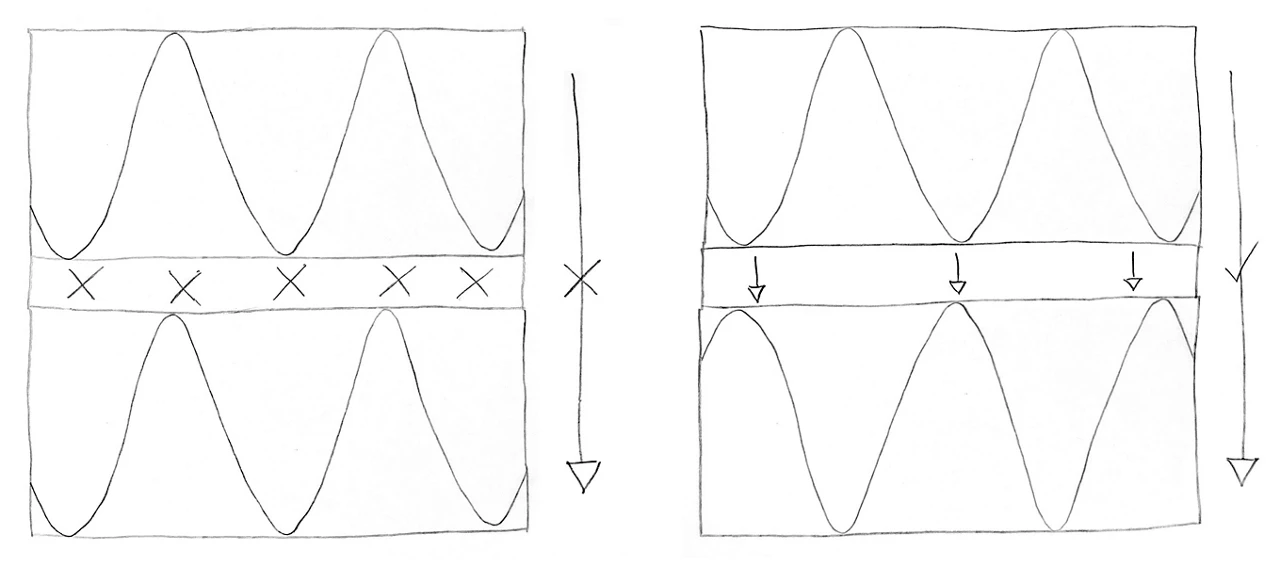

A sketch shows two devices with three layers each, with sinusoidal waves in the top and bottom layers. The left device has waves that match and is labeled with no tunneling indicated, while the right device has waves positioned such that they are mirror images across the middle layer with arrows indicating tunneling.

Quantum tunneling of electrons in Josephson junctions occurs only when the phases of the two superconductors are aligned in a particular way.

Credit:

Yang H. Ku/C&EN

Like classical bits, qubits carry information. But unlike the strict 0 or 1 value of classical bits, qubits can exist as a superposition, a uniquely quantum combination of both states at once. This superposition enables quantum computers to compute many possibilities at the same time, in principle giving them an advantage over classical machines. When many qubits made of superconducting circuits with Josephson junctions are put together and held at ultracold temperatures (a few millikelvin), they function as a quantum computer.

Josephson junctions are so integral to quantum computing that their discovery won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics.

The junction used today

The most common Josephson junctions used by academic labs and companies such as Google and IBM are built from aluminum. Aluminum serves as the superconducting layers, and aluminum oxide as the insulating barrier between them.

Al–Al oxide junctions are popular in part because they are easy to make. Engineers make them by depositing a thin layer of aluminum on silicon or other substrates using vacuum techniques such as shadow evaporation. In this method, metal is deposited through a tiny suspended stencil to create small, precisely aligned structures. Exposing the aluminum to oxygen at low pressure forms an aluminum oxide layer just a few nanometers thick. Depositing a second aluminum layer on top without breaking the vacuum completes the junction.

The result is a sandwich structure made in just two steps using common equipment. Labs with basic nanofabrication tools can make these devices. This simplicity has helped the field advance quickly so far.

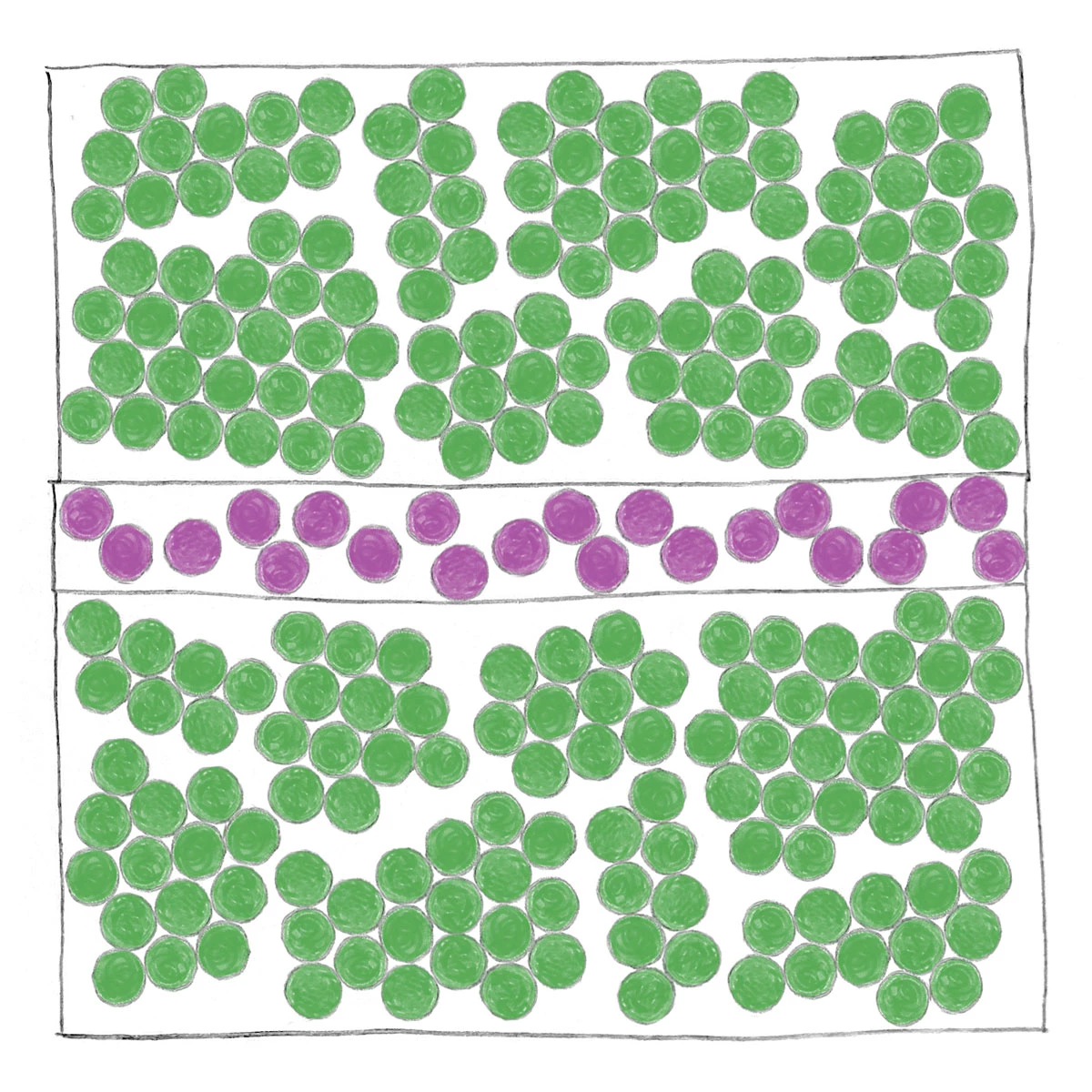

A drawing of a device with three layers has regions of partially aligned green dots in the top and bottom layers and randomly placed purple dots in the middle later.

In a standard aluminum-based junction, the top and bottom layers consist of polycrystalline aluminum. The middle layer is made of amorphous aluminum oxide. The interfaces are rough, and the oxide carries imperfections, causing instability.

Credit:

Yang H. Ku/C&EN

According to Nathalie de Leon, a quantum engineer at Princeton University, it’s the oxide layer that makes the process really special. When aluminum is exposed to oxygen, it forms an oxide layer that naturally stops growing at about 2 nm—almost exactly the thickness needed for a standard Josephson junction. That self-limiting behavior also makes the process remarkably reproducible. “The material’s natural tendencies line up beautifully with the needs of a quantum device,” de Leon says.

The catch is that the oxide layer is amorphous—its atoms are arranged in a disordered structure rather than a neat crystalline pattern. Defects in the material act like microscopic switches that randomly flip and perturb the junction. The rough Al–Al oxide interface can also trap charges. These effects give rise to two-level systems, or TLSs, which act as noise sources that blur the junction’s phase and push qubits out of their quantum states, contributing to decoherence.

Quantum computers today are plagued by decoherence, the process in which a system loses its delicate quantum properties. It is as if Schrödinger’s cat, the star of the famous thought experiment, lost its peculiar ability to be both dead and alive at the same time, and it had to remain either dead or alive. While this might be a better outcome for the cat, decoherence causes quantum computers to lose information.

The major source of decoherence today, however, is not TLS problems in the junction. “If you measure a single qubit and ask how much of the decoherence is coming from the junction, the answer is almost none,” de Leon says.

The reason things work today is because engineers connect the junctions to capacitors, relatively large energy-storage devices. This arrangement shields the junctions from energy that triggers the TLS problems, effectively hiding the imperfections from the qubit.

This work-around is successful in the small machines we use today. But de Leon argues that for larger and application-ready quantum computers, the material imperfections can no longer be avoided.

Scaling up means shrinking and packing more qubits on a chip. Fitting millions of junctions in a single processor would mean connecting large capacitors to each junction, which is impractical—especially since maintaining ultracold temperatures over large areas becomes increasingly expensive. This impracticality means that engineers can no longer afford to hide the junctions behind capacitors.

“If you want to make millions of qubits on a single chip, the qubits will have to go through something similar to the materials revolution that transistors went through in the fifties.”

Julian Steele, physics research fellow, University of Queensland

Another problem is that in large processors, there are many more TLSs that fluctuate independently and unpredictably. “This leads to instability,” de Leon explains. Qubits that work well most of the time can suddenly degrade when a defect lines up with the qubit’s phase. In small experiments, those rare events are manageable. “But in machines meant to run long, complex computations across thousands or millions of qubits, they become a serious liability,” she says.

For more than 2 decades, researchers have squeezed extraordinary performance out of aluminum-based junctions, pushing coherence times (the time before decoherence) from nanoseconds to milliseconds—long enough to run basic quantum computations. But according to de Leon, much of this progress came from designing circuits that carefully work around the junction’s imperfections.

This strategy has worked until now. But researchers are increasingly worried about tomorrow’s scales. Can millions of junctions each dotted with microscopic defects remain stable long enough to do useful work?

Many researchers agree that quantum computing hasn’t yet achieved the quantum advantage—experimental proof that a quantum computer is better than a modern classical supercomputer. To achieve that advantage, we must move past the era of quantum computing that we are currently in, known as the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era. According to de Leon, that progress means moving away from amorphous materials. “To get to a fully fault-tolerant system, we almost certainly need to make a big dent in the TLS problem,” she says. “We might need to move towards more-ordered crystalline systems.”

Junctions stacked like Post-it notes

Fong’s team at Northeastern is trying to solve the problem with a unique approach. Instead of relying on aluminum oxides to build Josephson junctions, they make them by stacking atomically thin crystals on top of one another, one layer at a time, like assembling a neat stack of Post-it notes. Conventional aluminum junctions, by contrast, are more like crumpled sheets of paper that are pressed and fused together.

These devices are known as van der Waals Josephson junctions. Their layers are held together by van der Waals forces—weak electrical attractions between atoms and molecules, akin to the gentle stickiness of Post-it notes but acting at the atomic scale.

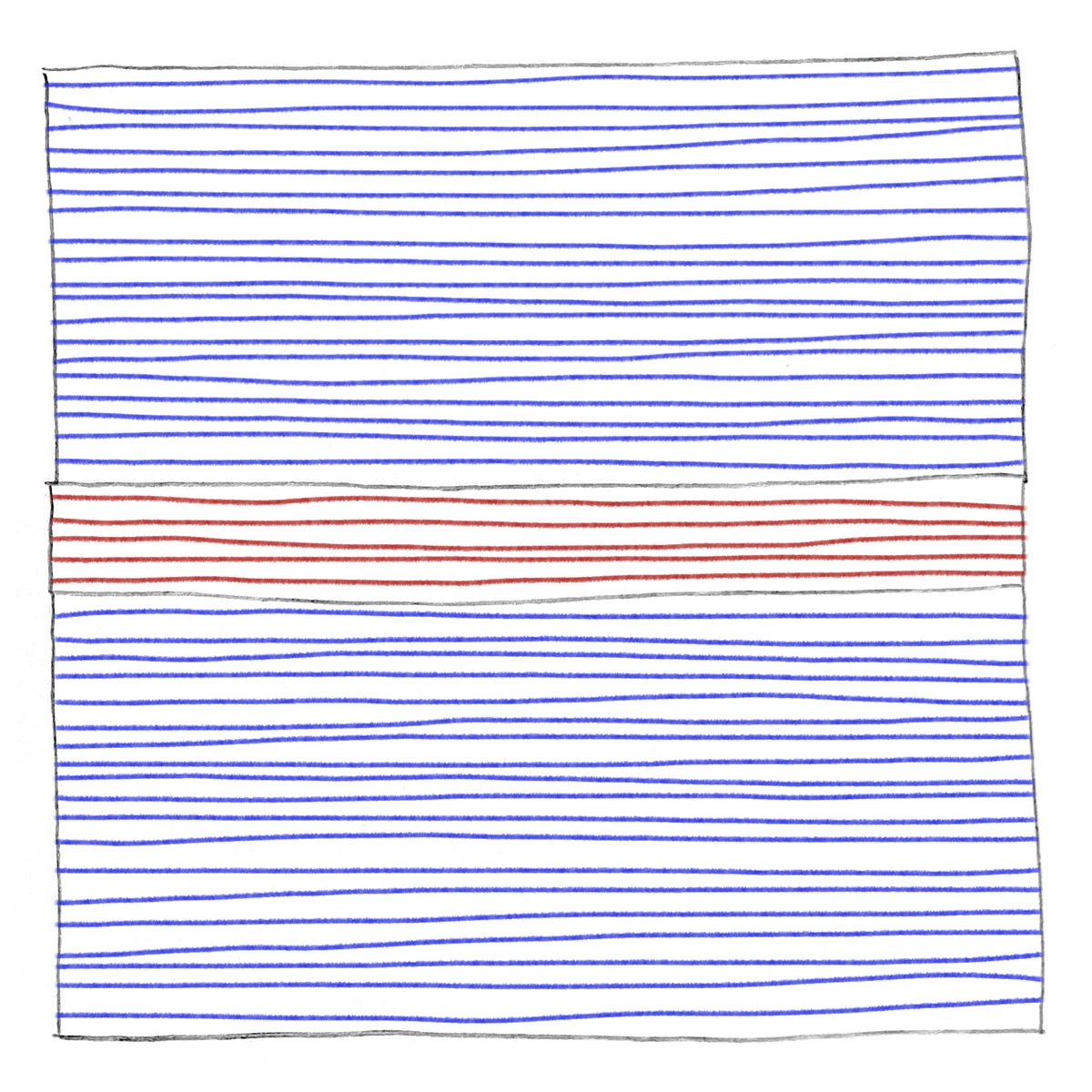

A drawing of a device with three layers has horizontal blue lines in the top and bottom layers and horizontal red lines in the middle layer.

Van der Waals junctions contain a stack of layers of niobium diselenide at the top and bottom. The middle stack is made of tungsten diselenide. The interfaces here are smooth, and each layer of the junction is crystalline.

Credit:

Yang H. Ku/C&EN

The team stacks niobium diselenide (NbSe2) superconducting layers around a few tungsten diselenide (WSe2) insulating layers, forming fully crystalline van der Waals junctions. Because the layers meet without forming chemical bonds, their interfaces remain smooth, clean, and crystalline—unlike the amorphous oxide barriers found in conventional aluminum junctions. Fewer imperfections and smoother interfaces mean fewer TLS problems and more-stable qubits (Precis. Chem. 2024, DOI: 10.1021/prechem.3c00126).

The junctions are assembled inside a nitrogen-filled glove box to protect the materials from air and moisture. Ultrathin crystals of NbSe2 and WSe2 are peeled using Scotch tape, lifting sheets just a few atoms thick. A soft polymer stamp picks up each flake and gently places it onto the next, forming a neat vertical stack. When the layers touch, van der Waals forces pull them smoothly into place, creating clean, uniform interfaces.

“It’s like playing with Legos,” jokes Jesse E. Balgley, a mechanical engineer at Columbia University who works with Fong.

The van der Waals junctions work at around 7–8 K, compared with aluminum’s 1 K, reducing the cooling efforts and making large-scale computing more efficient.

More recently, Fong’s team came up with a way to precisely control the number of layers in the WSe2 barrier, building one that was 17 sheets thick. This level of control, which is hard to achieve in aluminum junctions, enables researchers to fine-tune electron tunneling through the barrier (Phys. Rev. Appl. 2025, DOI: 10.1103/3ssz-jjt6).

Researchers can control the amount of energy that van der Waals junctions have by modifying the number of layers in the junctions. This feature enables the researchers to remove the large capacitors that engineers place in the circuit, making the circuit significantly smaller. Smaller qubits expose less surface area where defects can hide, pack more efficiently onto a chip, and reduce the amount of material that must be cooled.

The approach is not without limitations. In yet-to-be-published work, the team found their qubits retained quantum information for about 1–2 μs. That time is far longer than the time of early aluminum qubits but well short of today’s best aluminum-based devices.

By comparing various designs, the researchers traced much of the remaining loss to the WSe2 barrier, which absorbs a small fraction of the qubit’s energy over time. They believe this limitation can be overcome by further refining the material and fabrication process.

“Van der Waals materials are very attractive because you don’t have to worry about the interface,” de Leon says, but she worries about the scalability of such materials. Their refinement is not easy or standardized.

What makes the van der Waals approach compelling, according to Fong, is that the junction becomes an adjustable building block rather than a fixed component. The team is now further refining WSe2 and exploring alternative layered materials that may absorb less energy, with the goal of pushing coherence times higher while preserving atomic-scale control.

A semiconductor that turns into a superconductor

While Fong’s team uses low-tech tape to build their junction, Javad Shabani’s group at New York University, which works with Steele at the University of Queensland takes a decidedly high-tech route. The NYU researchers use an expensive, high-precision machine to assemble materials atom by atom.

Germanium has spent decades as a workhorse semiconductor. But in Shabani’s lab, it morphs into a superconductor. That switch forms the basis of a new kind of Josephson junction architecture. In Shabani’s design, superconducting germanium serves as the electrodes, separated by a thin insulating barrier made from silicon or nonsuperconducting germanium (Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41565-025-02042-8).

“The motivation was that to get to millions of junctions, it’s a lot easier if you use the existing infrastructure,” Shabani says. The same processes used in traditional chip manufacturing can be used to make these germanium-based junctions.

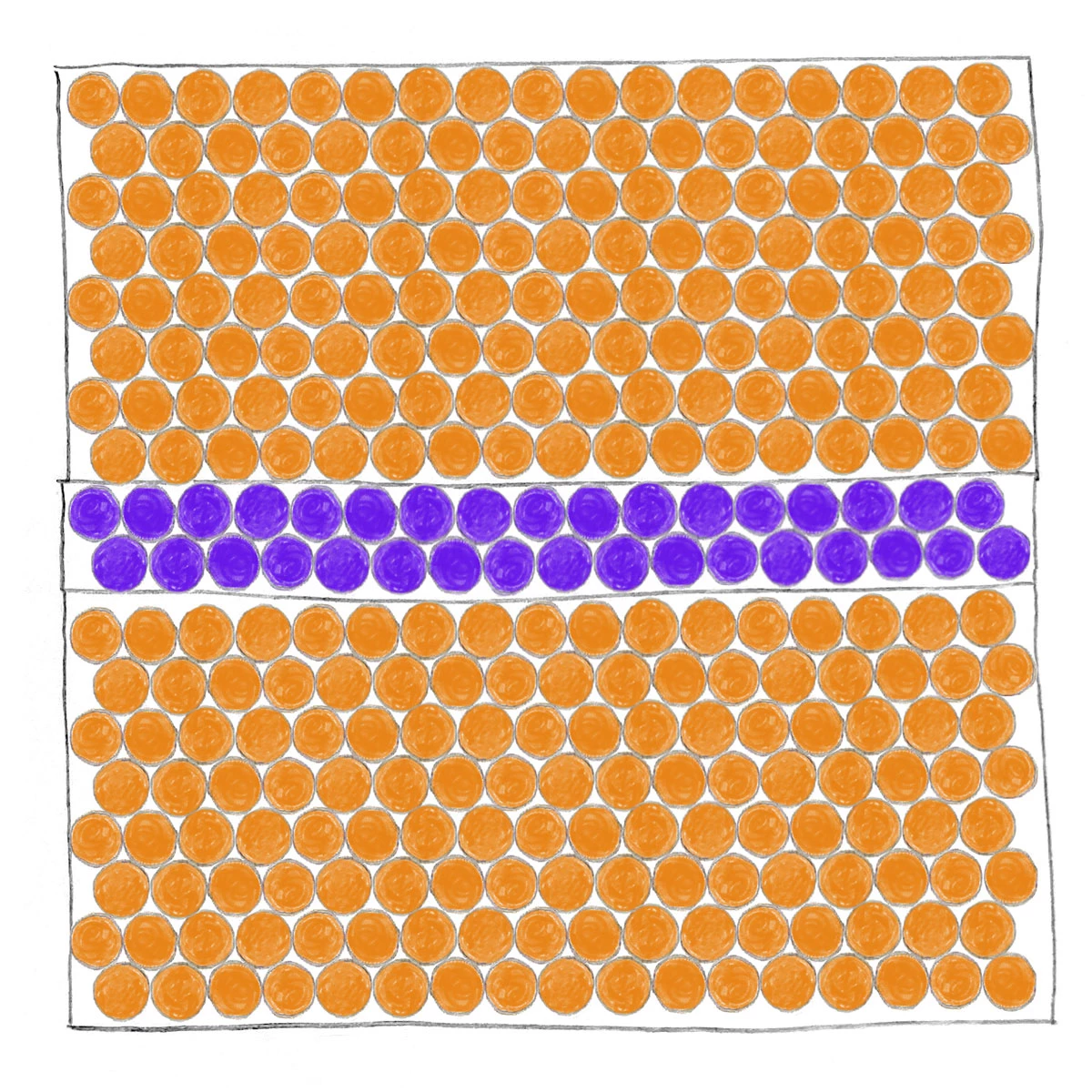

A drawing of a device with three layers has regions of aligned orange dots in the top and bottom layers and blue dots in the middle layer in complete alignment with the orange dots.

Crystalline semiconductor junctions are made of gallium-doped germanium for the top and bottom layers. The middle layer contains silicon. The interfaces are smooth and aligned, and the entire junction behaves like a single crystal.

Credit:

Yang H. Ku/C&EN

To make germanium superconduct, the team doped it with gallium using a process called molecular beam epitaxy, a vacuum technique that lets them assemble germanium and gallium one atom at a time. “We really took out one atom of germanium, then added an atom of gallium, and with that, we kept the crystal perfect,” Shabani says. The team grew an ordered thin film that contained far more gallium than germanium would normally accept. Under these conditions, the germanium lattice changed its structure to support superconductivity.

Earlier attempts struggled to keep germanium clean and uniform, especially at the low temperatures needed to preserve its superconducting state. This caused the gallium dopants to clump into tiny metallic pockets, raising doubts about whether the superconductivity came from germanium.

In the films at NYU, gallium atoms occupied regular lattice sites, turning the germanium layer uniformly superconducting. On top of this layer, the team deposited silicon, also using epitaxial growth, causing each atomic layer to align precisely with the crystal structure beneath it. This creates a single, continuous framework from bottom to top. The degree of order here leaves little room for the kinds of structural imperfections that typically appear when materials with different properties are stitched together.

“This is exciting,” Columbia’s Balgley says. “It shows that epitaxial fabrication is possible even at relatively low temperatures.”

“In the material science world, if you want to grow two materials on top of each other, you really have to make sure the lattice matches,” Shabani says. This alignment is what makes their architecture especially well suited to Josephson junctions. The superconducting layers and the thin barrier align naturally. The result is a crystalline junction from end to end, avoiding the disorder introduced by the amorphous oxide barriers used in aluminum junctions. “Nobody has been able to stack a superconductor on a nonsuperconductor in a crystalline format like this,” Shabani says.

“I don’t see any reason why crystalline materials can’t completely replace aluminum in the future.”

Jesse E. Balgley, postdoctoral research scientist in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University

The gallium-doped germanium films survive standard device-processing steps, such as lithography and plasma etching, without losing their superconducting behavior—an essential requirement for building complex circuits on a chip. Taken together, stacking these familiar semiconductor materials points toward Josephson junctions that are more uniform, less noisy, and more compatible with the manufacturing tools already used to make modern electronics.

For now, Shabani’s group stops short of a working Josephson junction. In the structures reported in their recent study, the silicon barrier between the superconducting germanium layers is only about a nanometer thick—likely too thin to produce clear tunneling. According to lead author Steele, thicker barriers, closer to 5–10 nm, are the next step. “I think this is more than speculative,” he adds, saying it may someday contribute to real chip manufacturing.

“What we have done is a materials science study,” Shabani says. “If we go to the next step,” work out the kinks, and measure the qubits, “they might turn out to be phenomenal.”

So many junctions for quantum computing!

Josephson junctions based on aluminum, van der Waals materials, or germanium are just a small slice of the approaches researchers are exploring. Despite the growing burst of materials exploration, no alternative junction has yet matched the coherence times achieved by standard aluminum-based qubits. That limitation is one reason the field remains anchored to aluminum today.

“Aluminum junctions are certainly a powerhouse,” Balgley says. According to him, these amorphous materials are really limiting how small the qubits can get. Also, the high coherence time of a single qubit does not translate to better performance when scaled. “I don’t see any reason why crystalline materials can’t completely replace aluminum in the future,” he says.

Abandoning aluminum isn’t the only option. Some researchers are trying to replace aluminum oxide with other amorphous oxides that host far fewer defects. Others push aluminum oxide closer to a crystalline form. Such research means the path forward could involve refining the junction’s materials rather than replacing them.

Researchers around the world are drawing from a large palette of materials, comprising a range of metals, semimetals, and alloys. Many of these ideas are still early and unproven. Making progress, de Leon says, will require a more “muscular” research effort, one that pushes materials development, characterization, and device testing in parallel rather than waiting for a perfect candidate to emerge.

“I think every material has its place,” Balgley says. Modern electronics use various kinds of transistors optimized for different applications. “Maybe something similar will happen for quantum computers,” Fong says. “We have a whole zoo of junctions with different functionalities to work with.”

“I haven’t seen any evidence so far that anyone has been able to do anything to the Al-Al oxide junction that actually makes it better.”

Nathalie de Leon, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, Princeton University

De Leon emphasizes that even ideas that never make it into a commercial device can still move the field forward. Exploring “crazy” systems, she argues, isn’t wasted effort, as each attempt teaches researchers something—about defects, interfaces, loss mechanisms, or fabrication—that feeds back into improving other platforms.

Not everyone is convinced this path is a fight worth pursuing. Some researchers and industry experts have publicly expressed deep skepticism that a fundamentally new Josephson junction can ever be built. Even de Leon does not rule out the possibility that aluminum itself could ultimately prevail. There may yet be a way—through better oxidation, postprocessing, or interface control—to tame its defects enough for large-scale machines, she says.

“I haven’t seen any evidence so far that anyone has been able to do anything to the Al-Al oxide junction that actually makes it better,” she says. But she is careful not to close that door.

Still, de Leon agrees that these junctions need a materials makeover. Whether that makeover turns out to be redesigning today’s junction materials, replacing them entirely, or building an entire assortment of materials systems to be used as needed remains an open question—one that can be answered only by exploring many different materials today.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society