A leading political lobbyist has described the timing of a new initiative to increase state funding for New Zealand literature as the best of times and the worst of times. The worst of times seems to have the edge.

The mightiest quango in New Zealand literature, the Coalition of New Zealand Books, has the backing of 40 representatives from government ministries and the books sector as it prepares to knock on doors and present its new five-year strategic plan. Among the chief aims of the Mahi Tahi:2025-2030 document is to increase the funding pools for writers festivals and the Public Lending Right, modernise IP laws, include writers in diplomatic missions, and ultimately create a dedicated literary funding system similar to the recently established model in Australia.

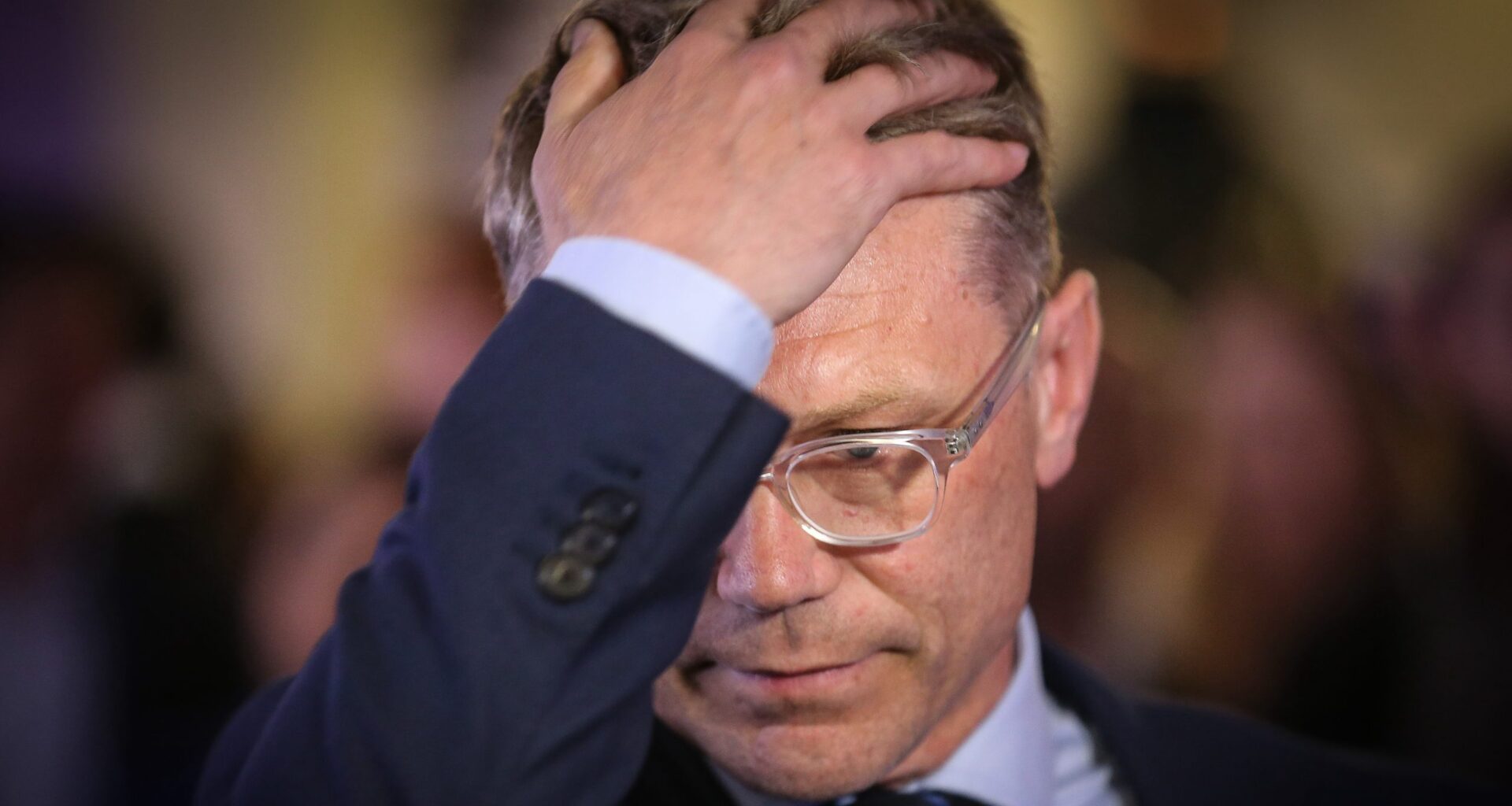

Essentially it sets out to boost local readership, improve literacy, and increase sales of New Zealand books. The Coalition—the literary one, not the National-led government one—represents a unified approach, a combined effort, a single voice. Well-known political insider and lobbyist Ben Thomas from Capital NZ regards that as a head-start.

“If you can unite people in the literary sector behind the agreed goals, then you’re ahead of most art sectors in terms of advocacy. It seems as though they do have got a united front and that sounds like a good thing for them.

“Right now it’s like the best of times, worst of times. You know, you’ve got a minister for the arts [Paul Goldsmith] who’s both very engaged in the arts and an author himself. So you could take a pretty good hearing at the political level, but of course, we’re in a fiscally constrained environment.

“You can’t control the fiscal situation obviously. You can only sort of control what you can control. And I guess any group advocating for more funding, then the things that you can control are your messages and your efforts to recruit people to your cause.”

Huzzah, then, to the Coalition of New Zealand Books, which represents publishers, the society of authors, booksellers, and other important components of the literary industrial complex. They are in supreme control of their message and their recruitment. As Coalition chair Mel Laville-Moore put it, “It’s about giving the appearance of being mobilised, of being something that’s bigger than all the little organisations within the sector. All of the state funders, like Creative New Zealand, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, the Ministry of Education, all of those folk, they’re just so used to having to deal with lots of small organisations all asking for lots of small things. And it’s never gone anywhere, whereas at least now, we’ve got a plan that we can all play to.

“So when somebody’s in front of Minister Goldsmith, or God help us if we can ever get in front of Brooke van Velden, God bless her, then we can say, ‘Here is the document to work from.’ And so it will literally involve us just constantly knocking on doors and constantly asking the questions and challenging the way in which arts funding is currently carved up.”

Van Velden is minister of internal affairs, which oversees the Public Lending Right. She has resisted meeting the New Zealand Society of Authors (NZSA) to discuss increasing the puny PLR funding pool. “You absolutely have to wish us luck there,” said Laville-Moore, “but we still have to try and have those conversations.”

NZSA claims the minister hasn’t responded to any of their attempts for a meeting. Asked what message that sends, Laville-Moore acknowledged, “To me it would say it’s not a priority for her. But even though there’s that disinterest there, it doesn’t mean we should give up.”

*

Arts minister Paul Goldsmith is seen as more sympathetic. Wellington lobbyist Ben Thomas said, “The issue is not necessarily Goldsmith’s receptiveness. It depends on the ask. And if the ask is just, ‘We would like more money because literature is good,’ then you’d probably find it pretty easy for people to agree with that second part, but not necessarily the first part.

“There are a lot of negative headwinds against any hopes of getting additional funding beyond what exists. The economy’s still got some, you know, issues to work through before we see that promised growth. The government is not flush with cash. And when they are restricting spending on everything else, you’re not going to see new money coming into the arts.”

There may even be less. In 2026, Creative New Zealand will scrap its long-established arts investment structure which guaranteed funding for three to five years for particular clients. Laville-Moore: “From a literature perspective, it will actually mean that from next year books has no guaranteed funding stream. Every single dollar that comes into the arts sector from government will be contestable. We’re going to be fighting with all of those other art forms.”

It strengthens the need for a single, separate body, like the New Zealand Film Commission. A better comparison is up and running across the Tasman. In July, the Albanese government launched Writing Australia. Arts minister Tony Burke announced, “Our writers, illustrators and publishers have been historically overlooked. Writing Australia and our funding will help rectify this.” The government is providing over $26 million in funding over three years, with ongoing funding of around $8.6 million annually to support the sector.

Mel Laville-Moore laughed for pretty much the only time in our interview, “How galling is it that the Australians got there first?” She continued, “Twenty six million dollars….I mean, can you imagine?”

I could not imagine, and only asked, “Is Writing Australia the exact model you want for New Zealand?”

“Precisely,” she said. “Yeah. Precisely.”

*

In the meantime, Laville-Moore already sees encouraging signs that government departments are taking a more serious approach to literature funding.

“We’ve got a little hint of that with that regeneration grant, which was the very last pot of cash that the Ministry of Culture and Heritage had with all of the COVID funding. It was the bit that was left after they’d given ridiculous sums of money to Narrative Muse.”

She meant the $500,000 that the Ministry wasted on the scarcely credible Narrative Muse outfit in 2021.

“They were far more careful and judicious with how that got carved up in the throes of that. The Coalition had lots of conversations with them and I think they are starting to get it.”

But there are signs that state funding for the books sector is in decline. These are anxious times for literary festivals and writers residencies. Laville-Moore: “They’re all a hugely valuable part of the ecosystem. Steve, you’re a very important part of that, with ReadingRoom, and I don’t know if we thank you enough for that. We possibly don’t. It’s so, so invaluable.”

ReadingRoom relies on CNZ funding. Its annual grant was spread over two years in the 2024 round. I said to Laville-Moore, “Personally I was grateful to get anything. Something is better than nothing. And anyway this particular government is trying to cut down on public spending and so it could be argued that your initiative could scarcely come at a worse time.”

“Oh, I agree,” she said. “But then there’s possibly never a good time either.”

It chimed with the comments of Ben Thomas. He formerly worked for Chris Finlayson, arts minister in the Key administration, and said, “Having worked in an arts minister’s office, there’s worse and better times to ask for anything. It just comes down to what’s in it for the government at the time, you know, whether it’s a policy which is politically beneficial to them.

“That’s probably it. And leveraging arts money for any government is usually pretty unpopular with the non-arts community, and generally hated by members of the arts community who aren’t the specific group being funded.

“So it’s a particularly tricky political proposition. There aren’t any votes in it.”

I asked Thomas, “Are you saying they don’t have a shitshow?”

He replied, “No, not if they have good policy that can appeal to the government’s needs. That’s essentially it. There’s no real magic to it. No one’s going to change policy or do funding as a favour. There has to be something in it for them. You have just got to put to the powers that be, who are holding the bank PIN number, that there are good reasons in line with their priorities for making that kind of shift in funding.”

Onwards, then, with the door knocking. I asked Mel Laville-Moore of the Coalition for New Zealand Books, “What happens now?”

She said, “The plan has gone out. We’re sending it to all of the various government departments and ministers that we were talking about. We’ve got the strategies. We’re asking, ‘What are the things we have to do to make it happen?’ And we need to start putting some timelines on it. But this is our starting point.”