A new study has revealed that microgravity reshapes the brain, causing it to shift within the skull, stretching and compressing in ways that affect balance and motor function. The findings, published in the journal PNAS, show that on Earth, gravity helps keep the thinking organ in place, while cerebrospinal fluid cushions it. In space, that constant downward pull disappears.

Scientists had already observed the brain shifting upward in orbit, but this new analysis reveals that it’s part of a broader deformation process, one with clear functional consequences for astronauts once they return.

Distinct Changes in Structure After Long Missions

According to Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at the University of Florida, led by Rachel Seidler, examined MRI scans from 26 astronauts before and after they spent time aboard the International Space Station. They compared these with scans from 24 Earth-based participants who underwent 60 days of bed rest at a six-degree downward angle, a technique used to simulate microgravity’s effects on bodily fluids.

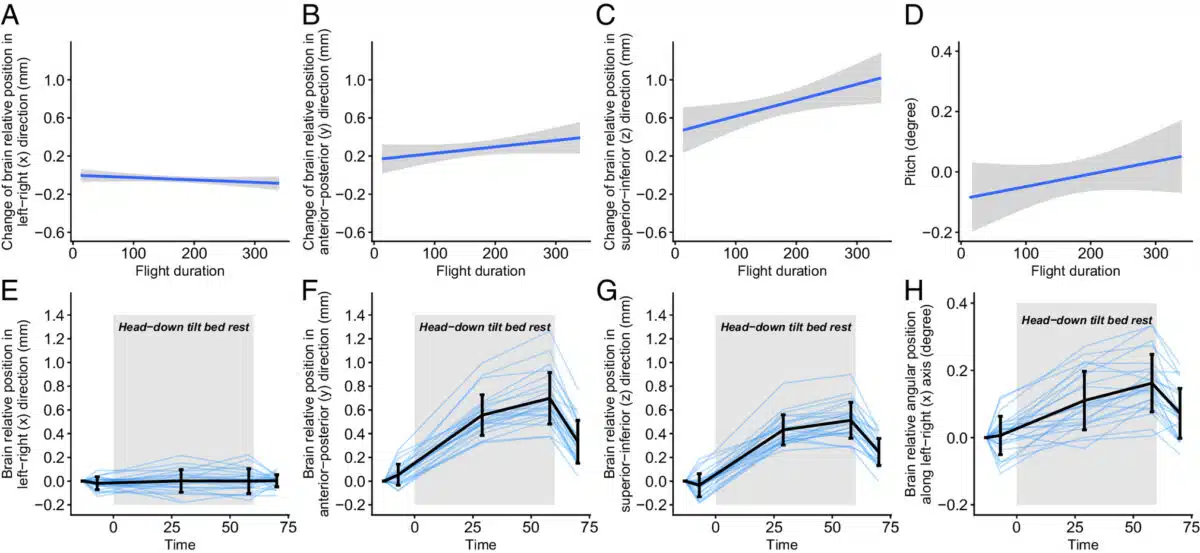

Position shifts with flight duration and during head-down tilt bed rest, shown across spatial axes and rotation. Credit: PNAS

Position shifts with flight duration and during head-down tilt bed rest, shown across spatial axes and rotation. Credit: PNAS

The differences were clear. While both groups experienced upward brain movement, astronauts’ brains shifted farther. The study found that the supplementary motor cortex, a region involved in movement control, moved upward by about 2.5 millimeters in astronauts who completed one-year missions.

Its movement was not uniform. As it shifted, it also became compressed at the top and back, while other regions showed stretching. These findings indicate that spaceflight changes the brain’s position and shape within the cranial cavity.

Why Astronauts Can’t Walk Straight After Space

The study also connected these structural changes to physical performance on Earth. It reports that astronauts who experienced larger brain shifts struggled more with balance tests after their missions. The implication is that the deformation may contribute to the postural instability often observed in returning astronauts.

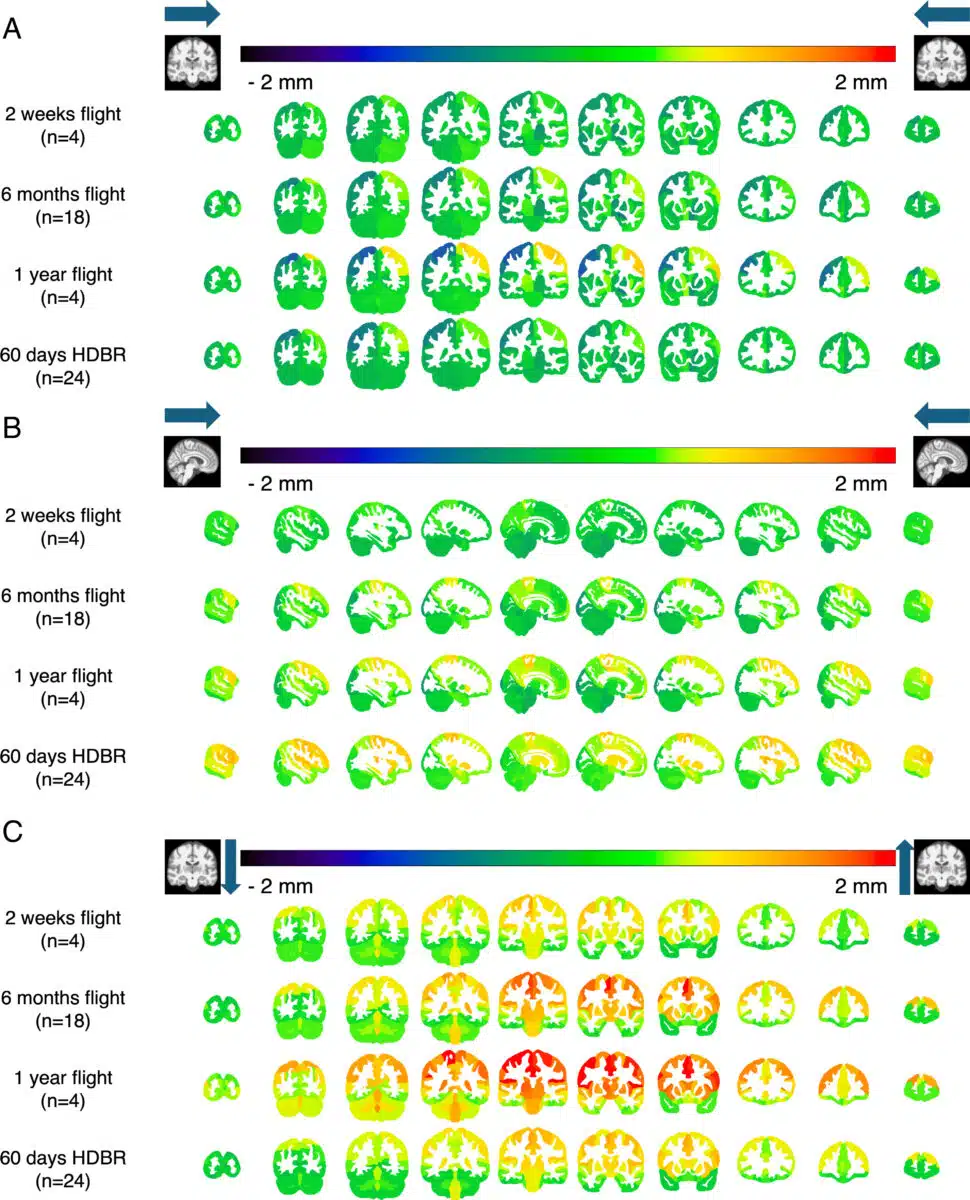

Visualization of brain displacement in astronauts after different durations of spaceflight. Credit: PNAS

Visualization of brain displacement in astronauts after different durations of spaceflight. Credit: PNAS

These changes may affect regions responsible for spatial orientation and movement control. The researchers emphasized that understanding the behavioral outcomes of neural tissue displacement is necessary to evaluate how space conditions affect performance.

Why Simulations Aren’t Enough

The researchers studied volunteers on Earth who underwent head-down tilt bed rest, a standard method used to mimic weightlessness. While these participants also showed brain movement, it was less pronounced than in the astronaut group.

“We demonstrate comprehensive brain position changes within the cranial compartment following spaceflight and an analog environment. These findings are critical for understanding the effects of spaceflight on the human brain and behavior,” explained the authors.

This suggests that real microgravity produces effects that simulated environments cannot fully recreate. The brain appears to respond in distinct ways when gravity is removed entirely, rather than simply redistributed. As noted by the researchers:

“The health and human performance implications of these spaceflight-associated brain displacements and deformations require further study to pave the way for safer human space exploration.”