Two dollars and seventy-nine cents. The price of a can of Wattie’s baked beans. That’s how much the Government’s planned rates rises caps is worth in forecast monthly savings to the average household.

Billing it as a solution to rising cost of living, Local Government Minister Simon Watts announced last month he would introduce a law to require councils to keep annual rates rises within a 2-4 percent band. “Rates are taking up more of household bills,” he said.

What he didn’t say in his media release would how much, or how little, those savings would be – despite having asked his officials for that figure.

The numbers – for what they’re worth – are revealed in official advice, published in the shadow of Christmas, and in the minister’s own report to his colleagues in Cabinet.

Asked whether it was worth the shemozzle of instituting a rates cap that would deliver people the equivalent savings of four cups of coffee a year, Watts is forthright.

“Yes, all savings are worthwhile,” he says this week. “Ratepayers have been clear that year on year double-digit rate increases are unsustainable and are putting immense pressure on household budgets.

“I often hear that ratepayers expect councils to be more disciplined in their spending. The rates cap will require councils to operate within a tighter funding envelope and, as a result, to live within their means.”

In the canned goods aisle at the Woolworths supermarket on Auckland’s Dominion Rd, shoppers’ views differ.

As he considered which baked beans to buy, Phil Ainsworth is dubious about implementing rates cap that will deliver his household a $2.79 monthly saving on rates rises. “That’s pretty small in the whole scheme of things, really,” he says.

“I think it’s more important for local authorities to be actually looking at what they’re spending money on and stick to core essentials, rather than capping rates. They really need to review the budgets they’re working on already.”

Other shoppers, though, say they’ll be glad of any saving on their rates bills. Kinjal, a mother or two, says cost of living increases have hit her family. “It’s impacted because the salaries are not high, but the rates and things are growing pretty fast, so it’s very hard to keep up with the expenses.

“Even baked beans are hard at the moment on people, as people are juggling their costs. Whatever is saved, it’s for the families.”

Another shopper, Sunny, says that if councils more clearly communicated the reasons for raising rates, then residents might be better able to decide whether those increases are justified. “I feel like my rates went up by quite a lot. I know family members whose rates have gone up even more than mine,” he says. “So baked beans might be the average saving, but a rates cap will save some households much more. For other people, it might be a grocery load.”

In an Internal Affairs briefing on October 29 last year, just before the minister took his proposal upstairs, the department’s general manager of local government policy, Rich Ward, hinted at his discomfort at being required to include a paragraph about the savings per household.

“It is difficult to quantify the average savings per household for a number of reasons, including local authority differentials and land valuations,” Ward replied to the minister’s office.

Instead, his staff quantified the average rates per capita for 2024 (excluding water rates), and how much would be saved per capita if councils had been limited to 4 percent rates rises, rather than the average 6 percent they actually imposed.

The difference was $22 – that’s how much a rates cap would have saved the average person that year.

“These savings will compound in the following years,” Ward added. “We could expect savings to be greater over time as councils catch up on underspend and operate closer to the lower end of the band.”

Of course, rates aren’t charged per capita. They are charged to “rating units” – that is, properties occupied by households and businesses, on the most part. This figure would probably be higher, but would also be more difficult to calculate, the briefing said, given councils’ ability to charge differently for different types of land and different land valuations.

A few days later on November 5, just in time for Watts to take his advice upstairs to the Cabinet economic policy committee, Rich Ward’s staff had another go at providing the minister an answer as he wanted, in a regulatory impact statement.

They dug out forecast rates revenue data and rating unit forecasts from 28 local authorities that had produced long-term plans for 2024 to 2034.

(They didn’t consider the planned rates rises for the other 50 local authorities because many hadn’t delivered the plans, counting regional councils might have meant double counting some households, and some councils like Wellington had data missing. Auckland Council’s planned rates rises were excluded because they were too low and might skew the national average rates data).

Once they’d removed the data that didn’t suit the analysis, they added up the rates that would be levied on the average rating unit (household or business) over the last seven years of the 2024-2034 long-term plans, and compared it with the rates that would be levied if those 28 councils were limited to increases within Watts’ 2-4 percent target band.

They concluded that these households or businesses would on average pay $938 less over those seven years – that’s $26,083, a total saving of nearly 3.5 percent.

Because this is a cumulative saving, the actual reduction in each annual rates rise is far less – just $33.50 a year, for the average household or business.

In other terms, that’s $2.79 a month saving on annual rates increases – exactly enough to buy a 420g can of Wattie’s baked beans at today’s prices.

This, said officials, “is likely to provide some relief to cost-of-living pressures”.

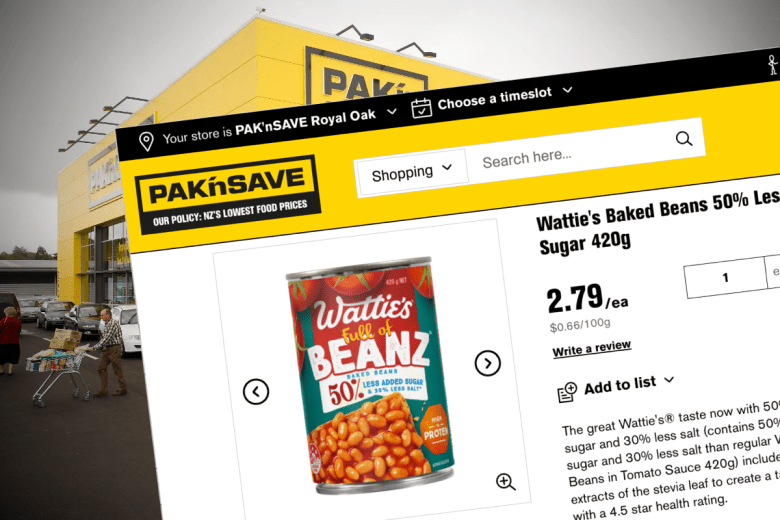

Pak’nSave is today charging $2.79 for a can of Wattie’s baked beans – that’s how much officials estimate the average household or business will save each month in rates rises.

Pak’nSave is today charging $2.79 for a can of Wattie’s baked beans – that’s how much officials estimate the average household or business will save each month in rates rises.

They did add a caveat: “This does not mean every ratepayer will have savings under a

rates target, but it indicates that total rates collection will decrease. As long-term plans change over time and are unreliable outside of the initial 3-year period, there is uncertainty on the scale of rates increases in the future.”

Unfortunately, as Watts pretty much conceded to his ministerial colleagues, a high-level departmental assessment of the quality of that regulatory impact statement had been scathing.

It had been rushed, the quality assurance panel said. There had been no public or stakeholder consultation. It sought to deal with an extremely complex area with just a narrow range of options, that were constrained by earlier Cabinet decisions to progress a rates cap, sight unseen.

The proposal was “incomplete in design and operational detail” and ministers didn’t have enough information to make properly informed decisions.

There was a mismatch between the problem as ministers perceived it (lack of fiscal discipline by local authorities) and the actual evidence (that councils were subject to unavoidable cost pressures).

In short, the official advice “fails to maintain a consistent focus on the identified problem and strays at times into discussion of limiting local authority expenditure decisions, rather than rates increases”.

Essentially, officials had identified a credible problem with the impact of recent sudden and high rates increases on ratepayers trying to budget their household costs – but they’d been captured by ministers’ perceptions of excessive council spending, rather than seeking solutions to the actual problem.

Despite the quality assurance panel’s strongly-worded concerns and insistence that ministers didn’t have enough information to make properly informed decisions, they went ahead and decided to proceed with Watts’ rates capping.